1.5 — Coordination Games & Multiple Equilibria

ECON 316 • Game Theory • Fall 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/gameF21

gameF21.classes.ryansafner.com

Coordination Games

Coordination Games

This semester, we are dealing with non-cooperative games where each player acts independently

In coordination games, players don't necessarily have conflicting interests

- Often positive-sum games

- Often have more than one, or zero, Pure Strategy Nash equilibria (PSNE)

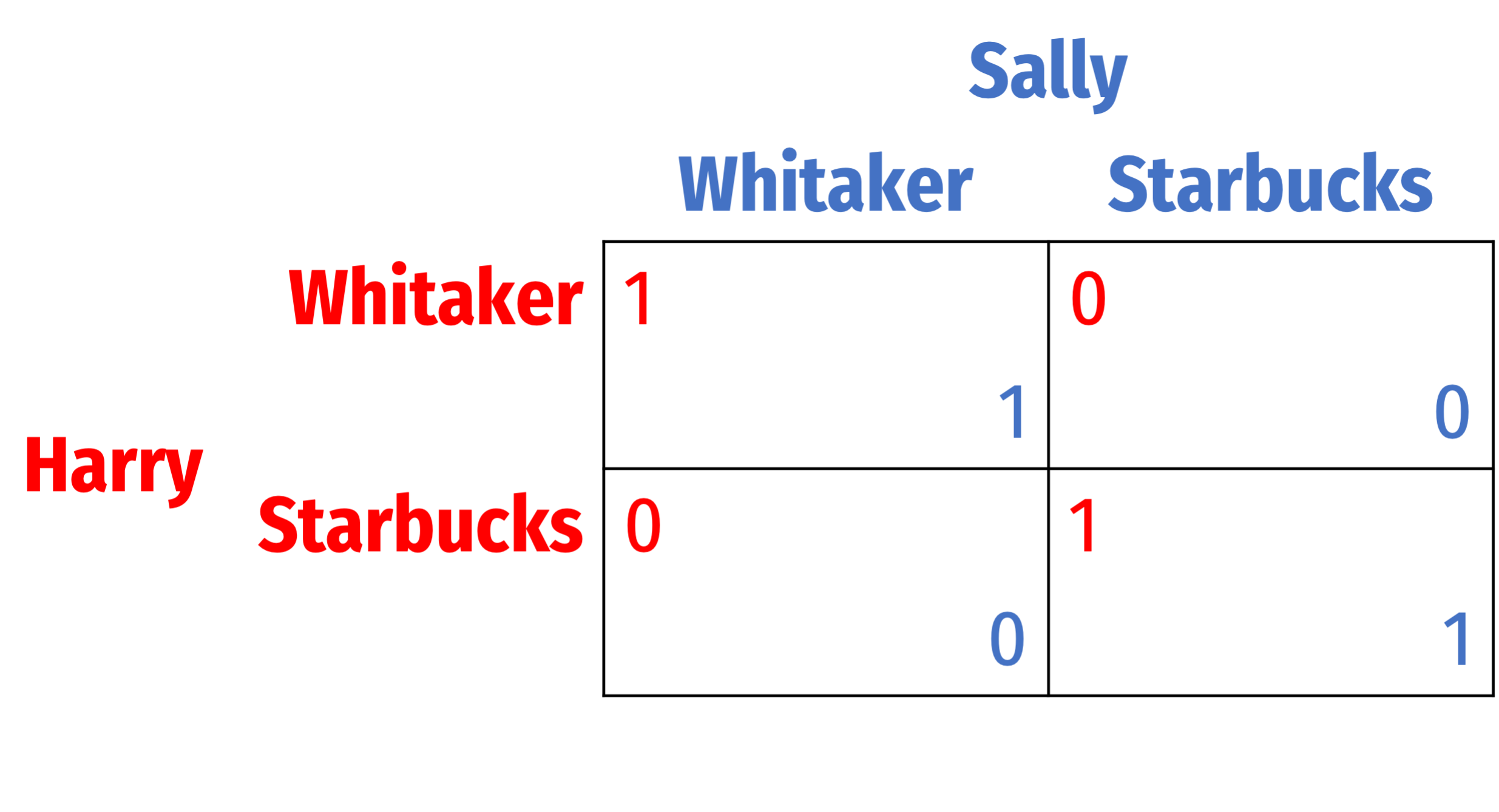

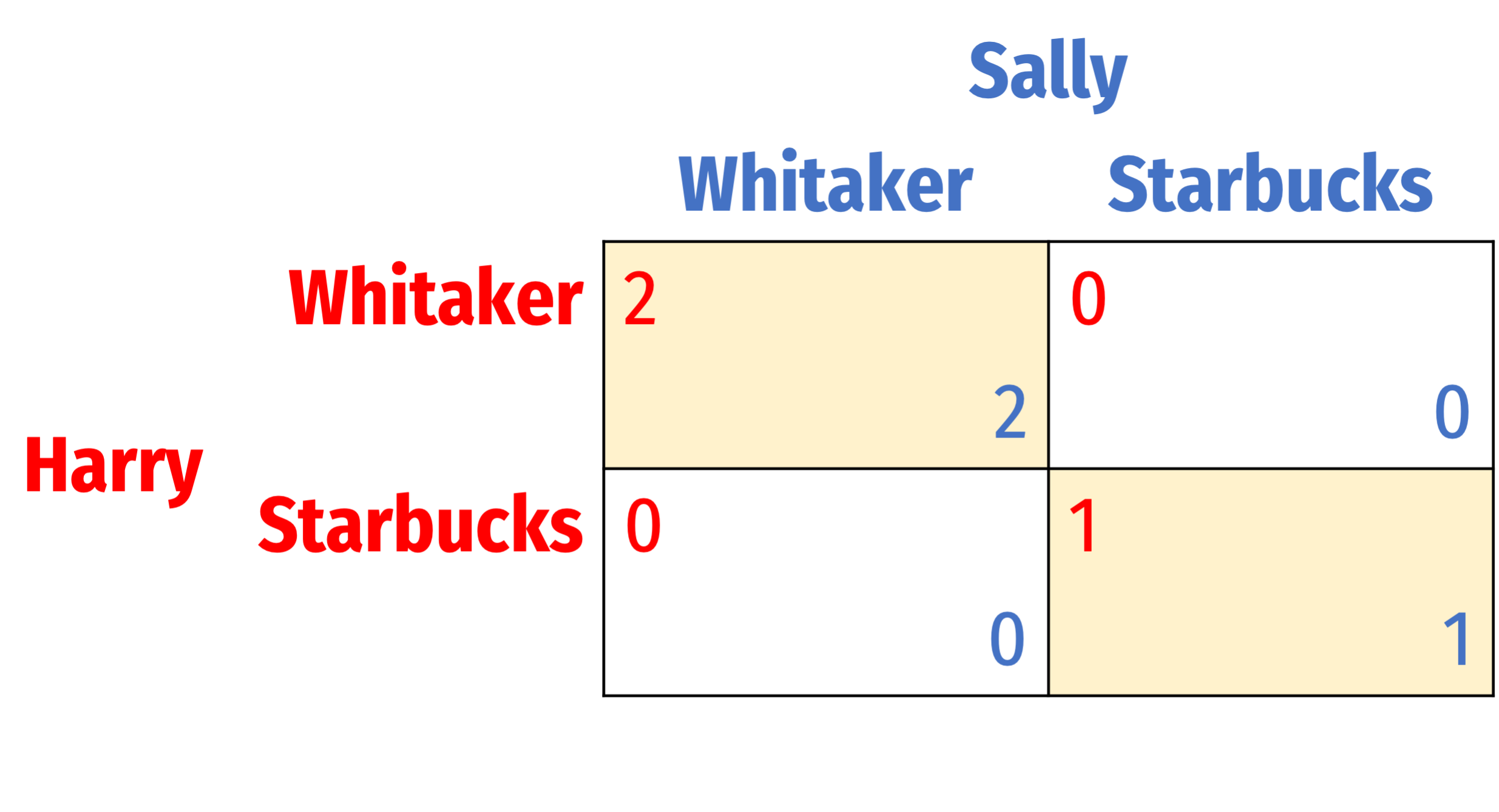

Pure Coordination Game

- Pure coordination game: does not matter which strategy players choose, so long as they choose the same!

Pure Coordination Game

Pure coordination game: does not matter which strategy players choose, so long as they choose the same!

Two Pure Strategy Nash Equilibria:

- (Whitaker, Whitaker)

- (Starbucks, Starbucks)

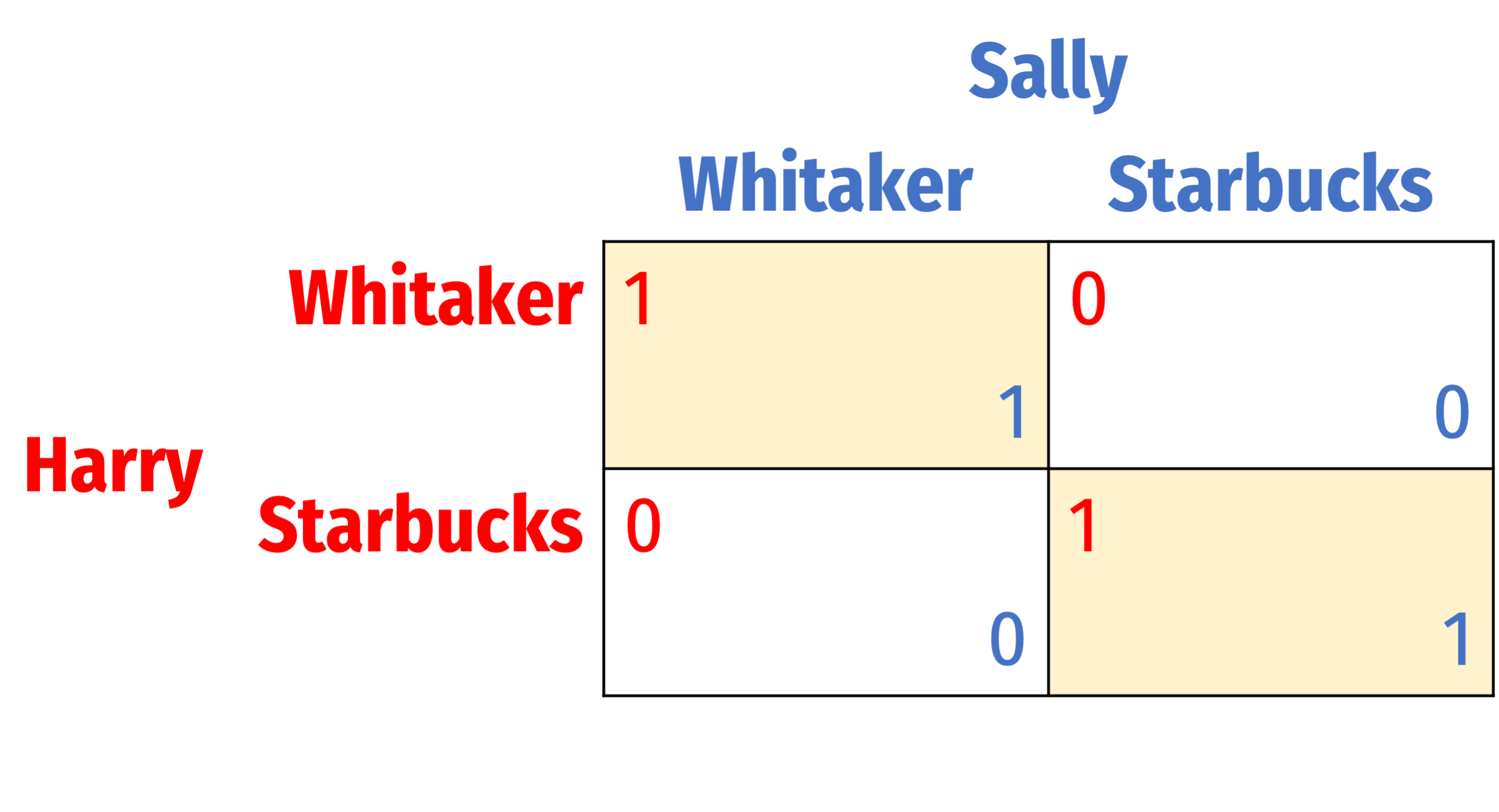

Pure Coordination Game

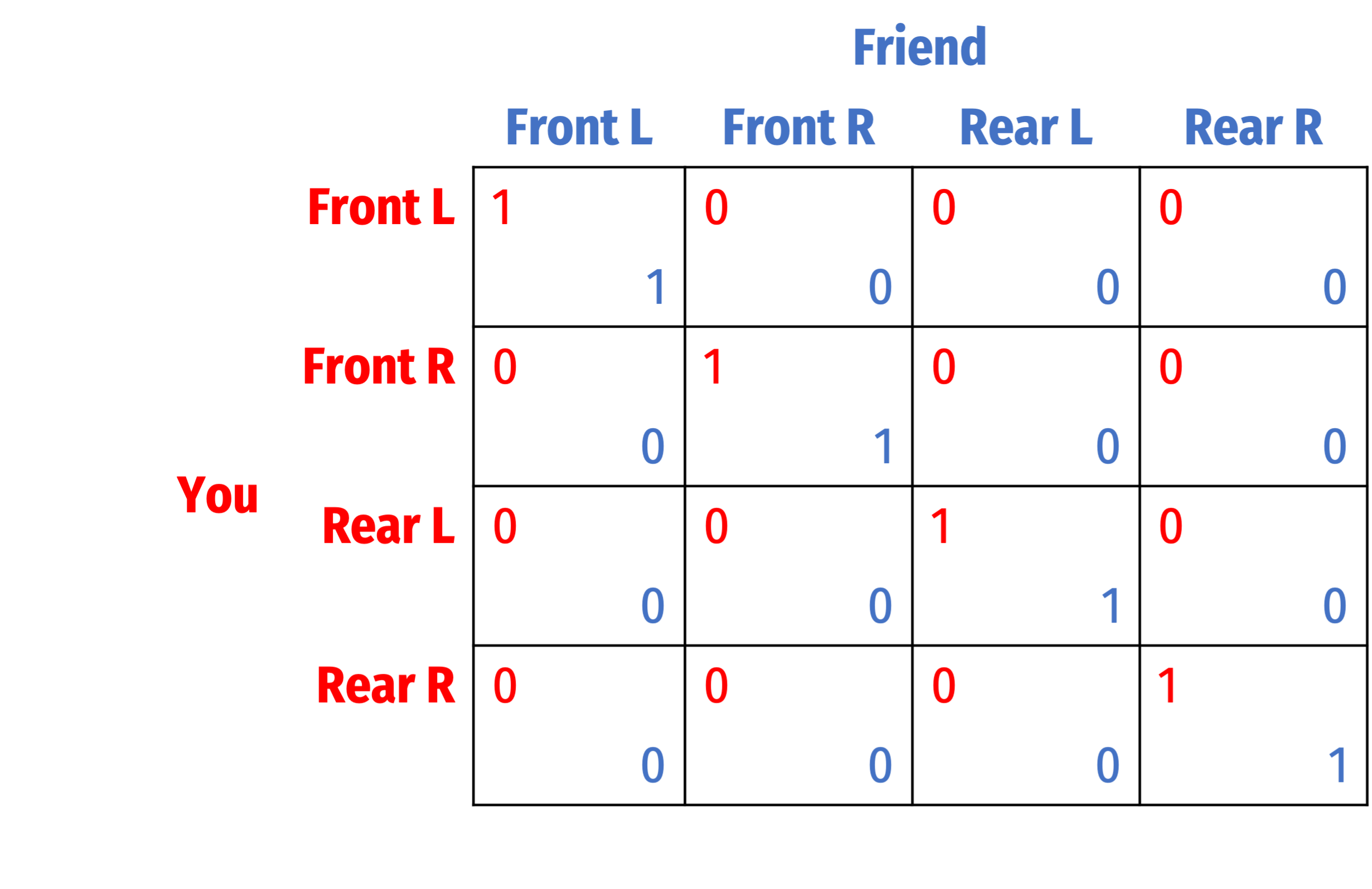

The flat tire game from before is also a pure coordination game

Four PSNE:

- (Front L, Front L)

- (Front R, Front R)

- (Rear L, Rear L)

- (Rear R, Rear R)

Coordination Games: Focal Points

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

Without pre-game communication, expectations must converge on a focal point

A major idea in Thomas Schelling's work, we often call them “Schelling points”

Coordination Games: Focal Points

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“[I]t is instructive to begin with the...case in which two or more parties have identical interests and face the problem not of reconciling interests but only of coordinating their actions for their mutual benefit, when communication is impossible.”

“When a man loses his wife in a department store without any prior understanding on where to meet if they get separated, the chances are good that they will find each other. It is likely that each will think of some obvious place to meet, so obvious that each will be sure that the other is sure that it is ‘obvious’ to both of them. One does not simply predict where the other will go, since the other will go where he predicts the first to go, which is wherever the first predicts the second to predict the first to go, and so ad infinitum.”

Coordination Games: Focal Points

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“What is necessary is to coordinate predictions, to read the same message in the common situation, to identify the one course of action that their expectations of each other can converge on. They must ‘mutually recognize’ some unique signal that coordinates their expectations of each other. We cannot be sure that they will meet, nor would all couples read the same signal; but the chances are certainly a great deal better than if they pursued a random course of search.” (p.54).

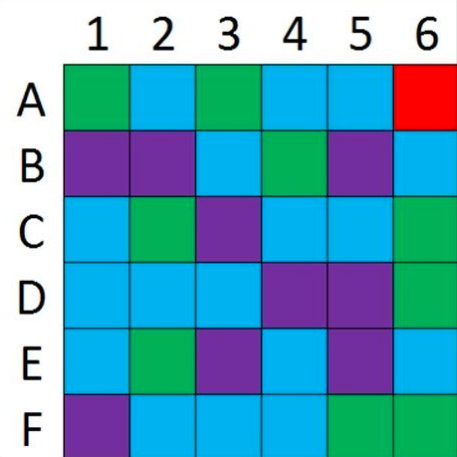

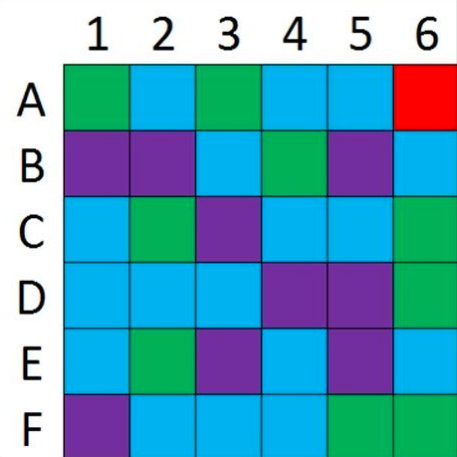

Coordination Games: Focal Points

Example

- If we both pick the same square (without communicating), we each get $100

- Which one would (should?) you choose?

Coordination Games: Focal Points

Example

- If we both pick the same square (without communicating), we each get $100

Which one would (should?) you choose?

Culture and informal norms (“unwritten laws”) play an enormous role!

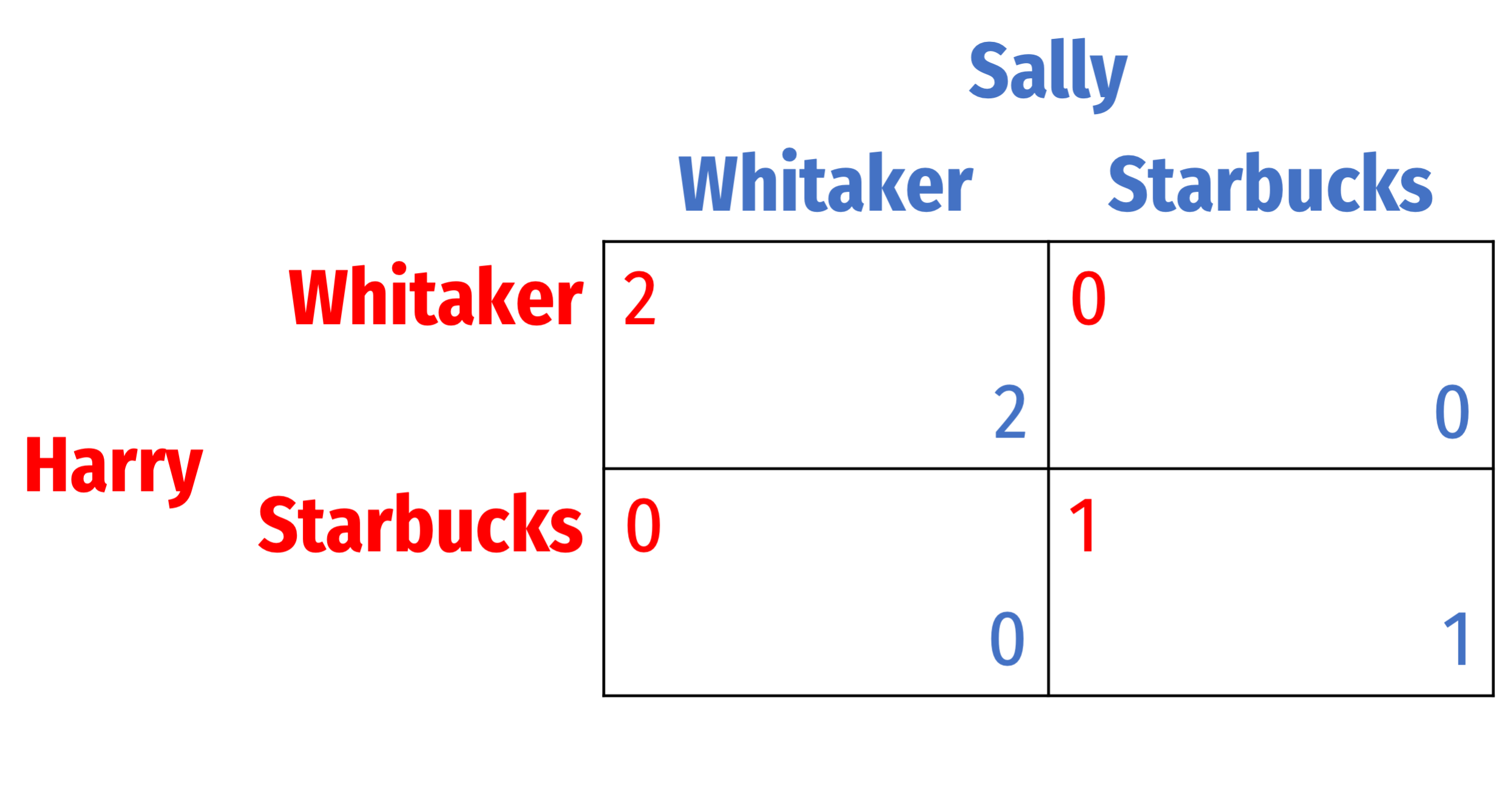

Assurance Games

“Assurance” game: a special case of coordination game where one equilibrium is universally preferred

Here, both prefer (Whit, Whit) over (SB, SB)

Assurance Games

“Assurance” game: a special case of coordination game where one equilibrium is universally preferred

Here, both prefer (Whit, Whit) over (SB, SB)

Still two PSNE

- (Whit, Whit)

- (SB, SB)

Players get their preferred outcome only if each has enough assurance the other is likely to pick it

Assurance Games: A Famed Example

Assurance Games: A Famed Example

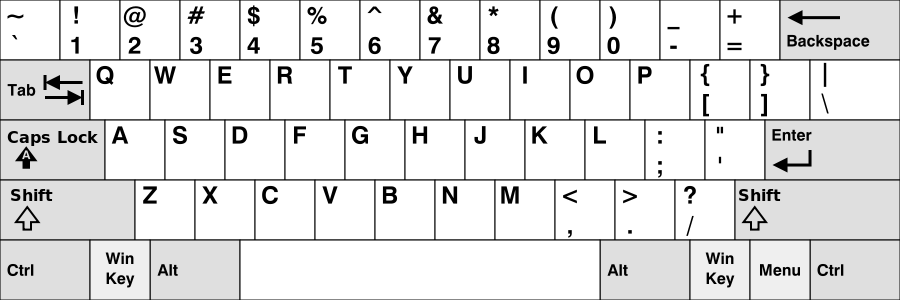

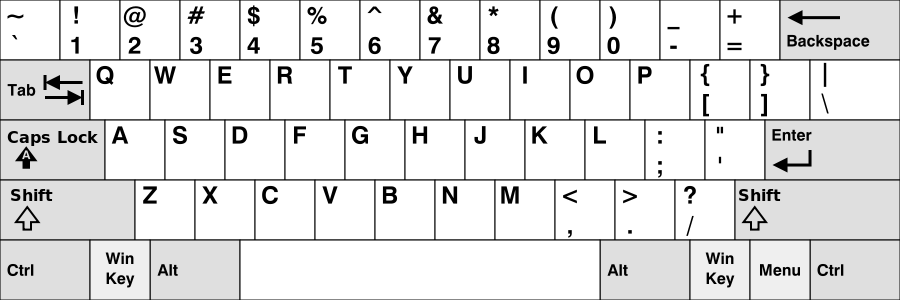

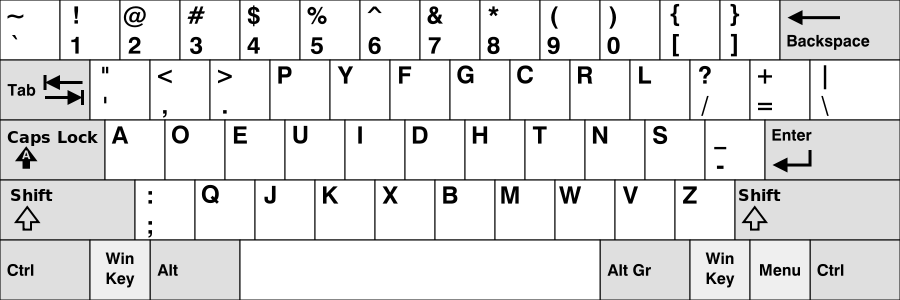

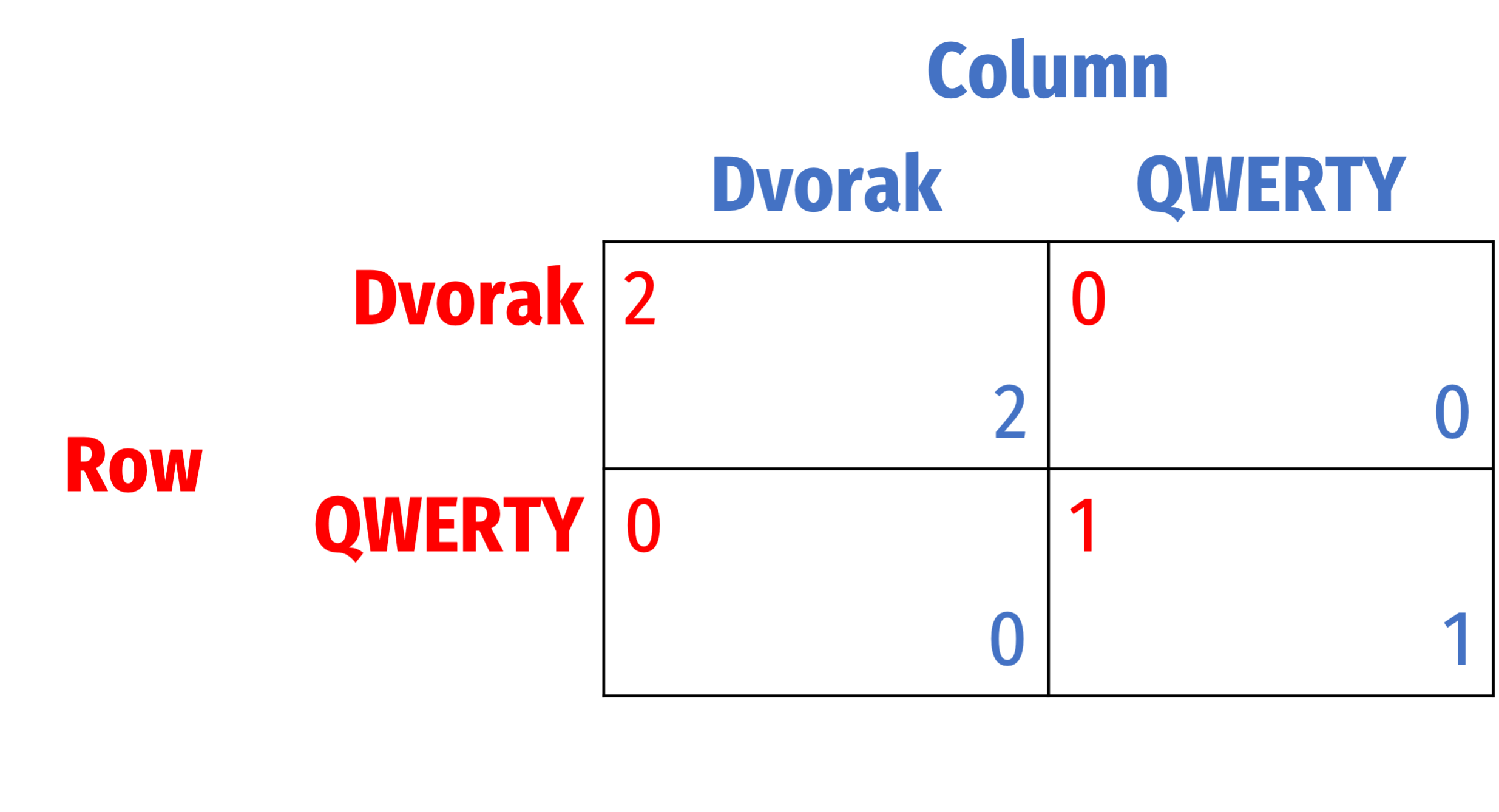

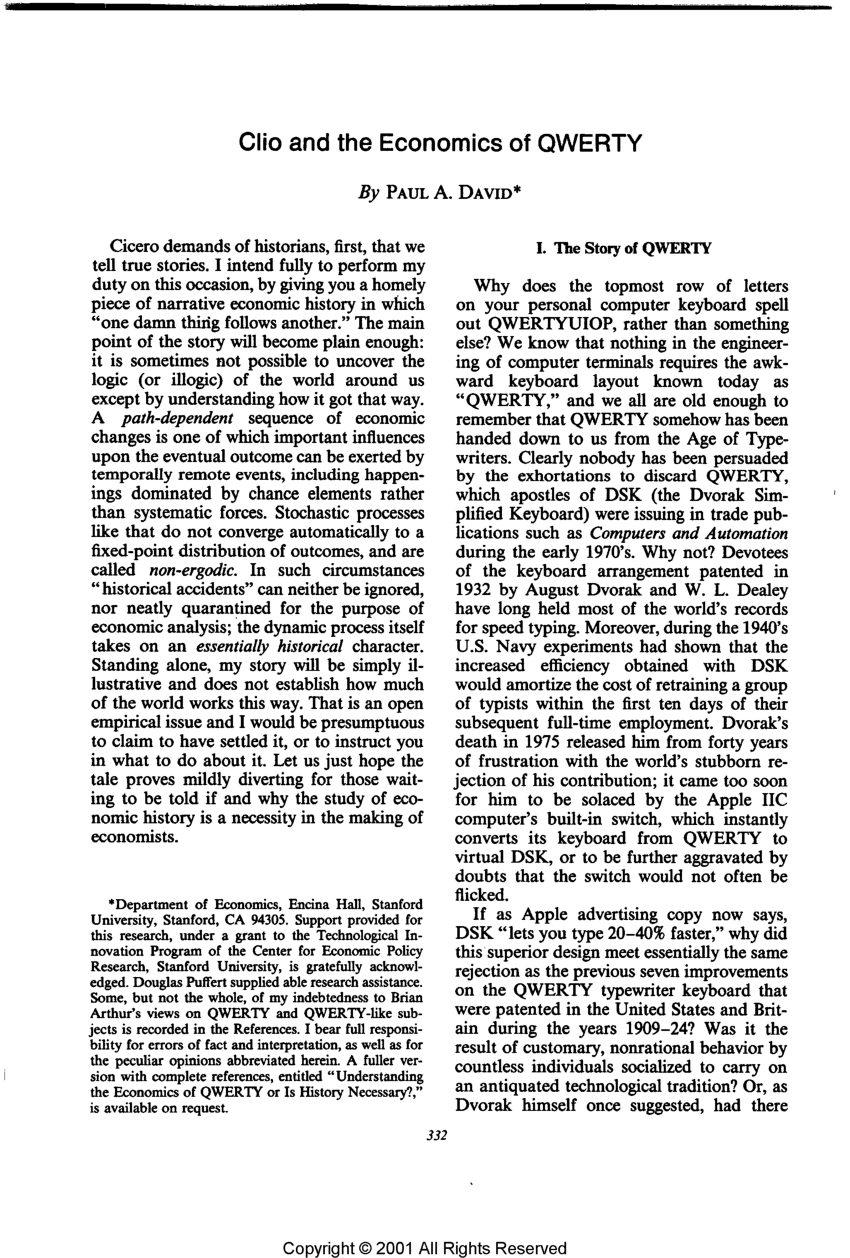

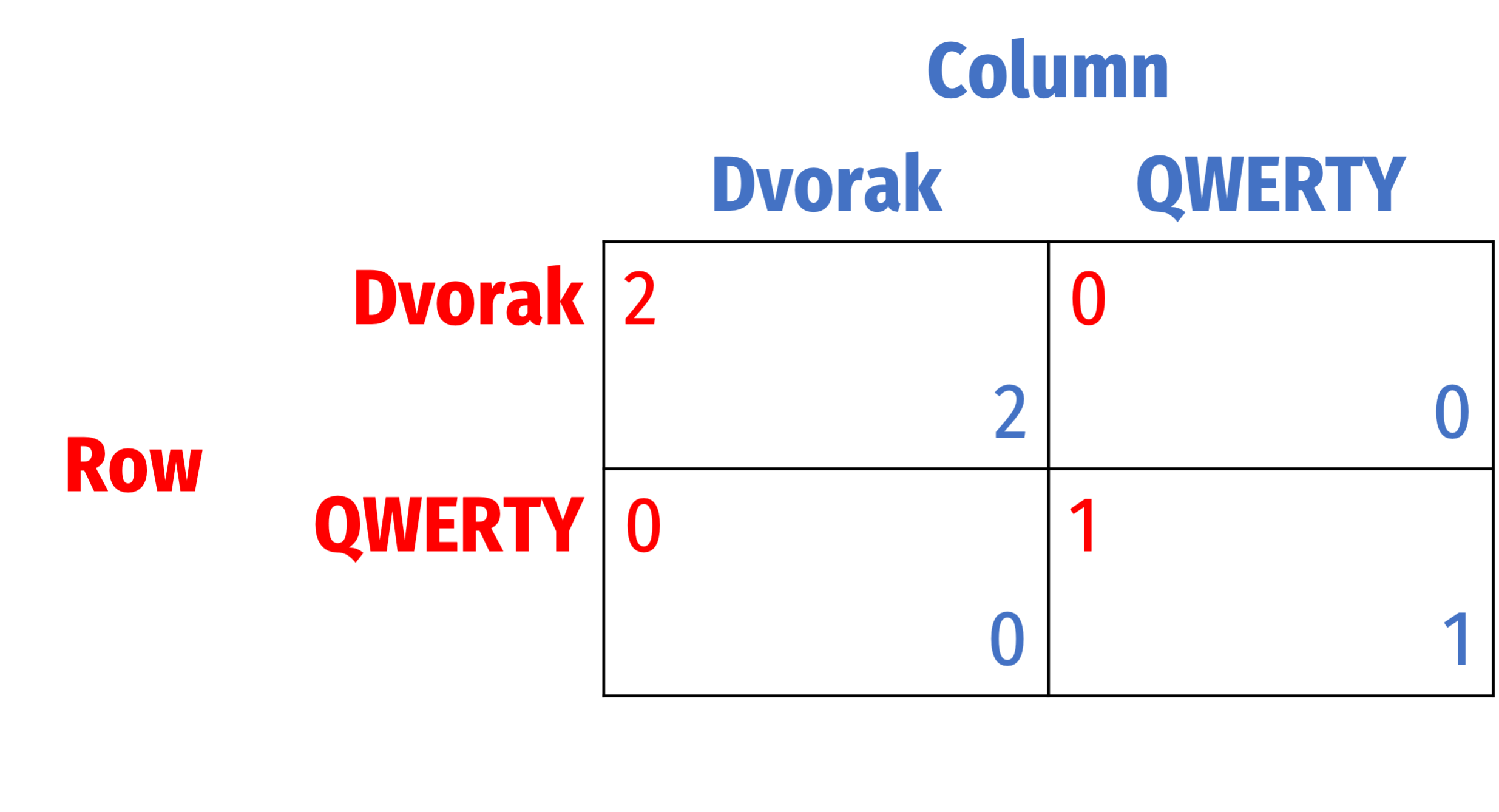

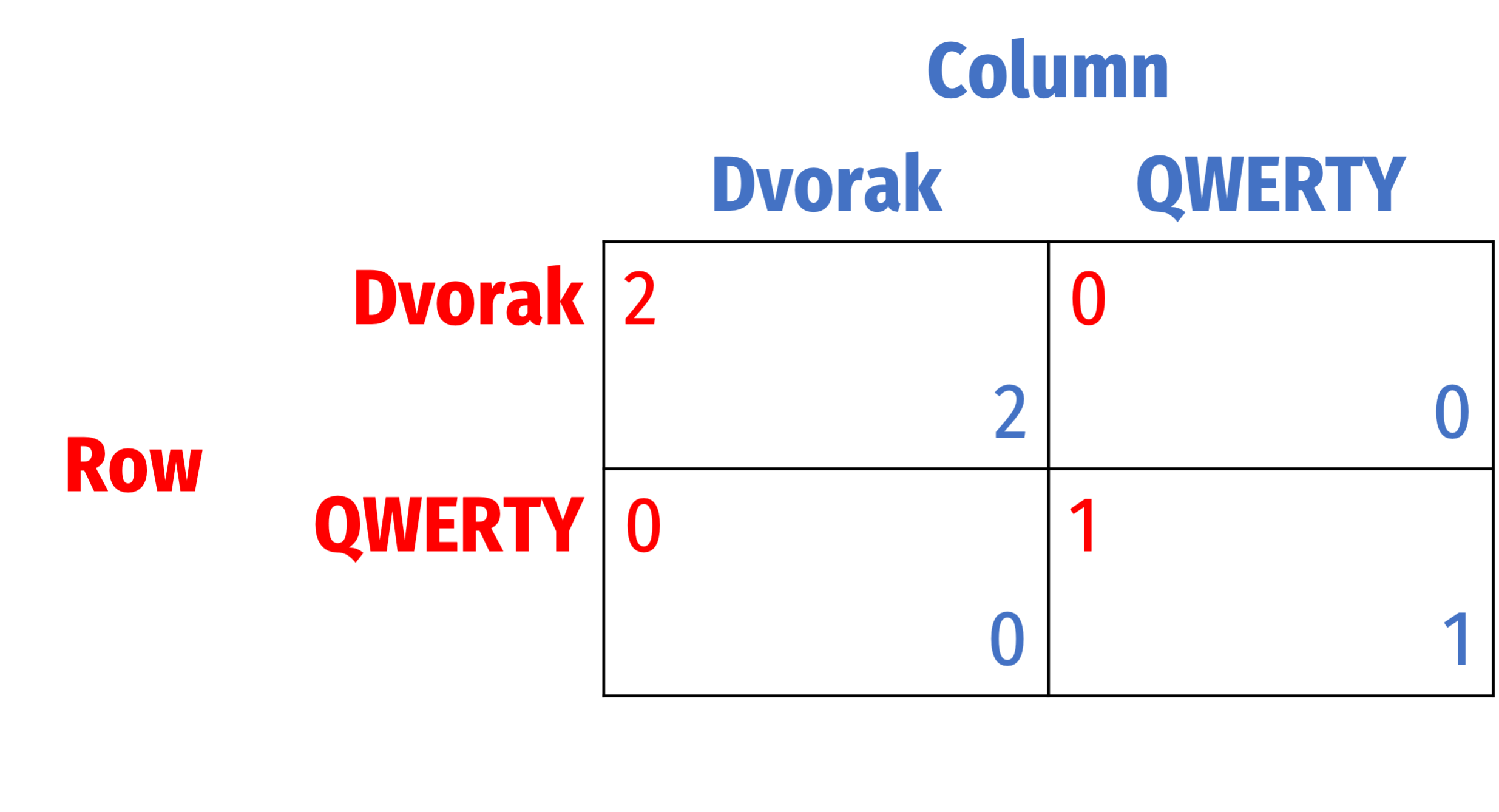

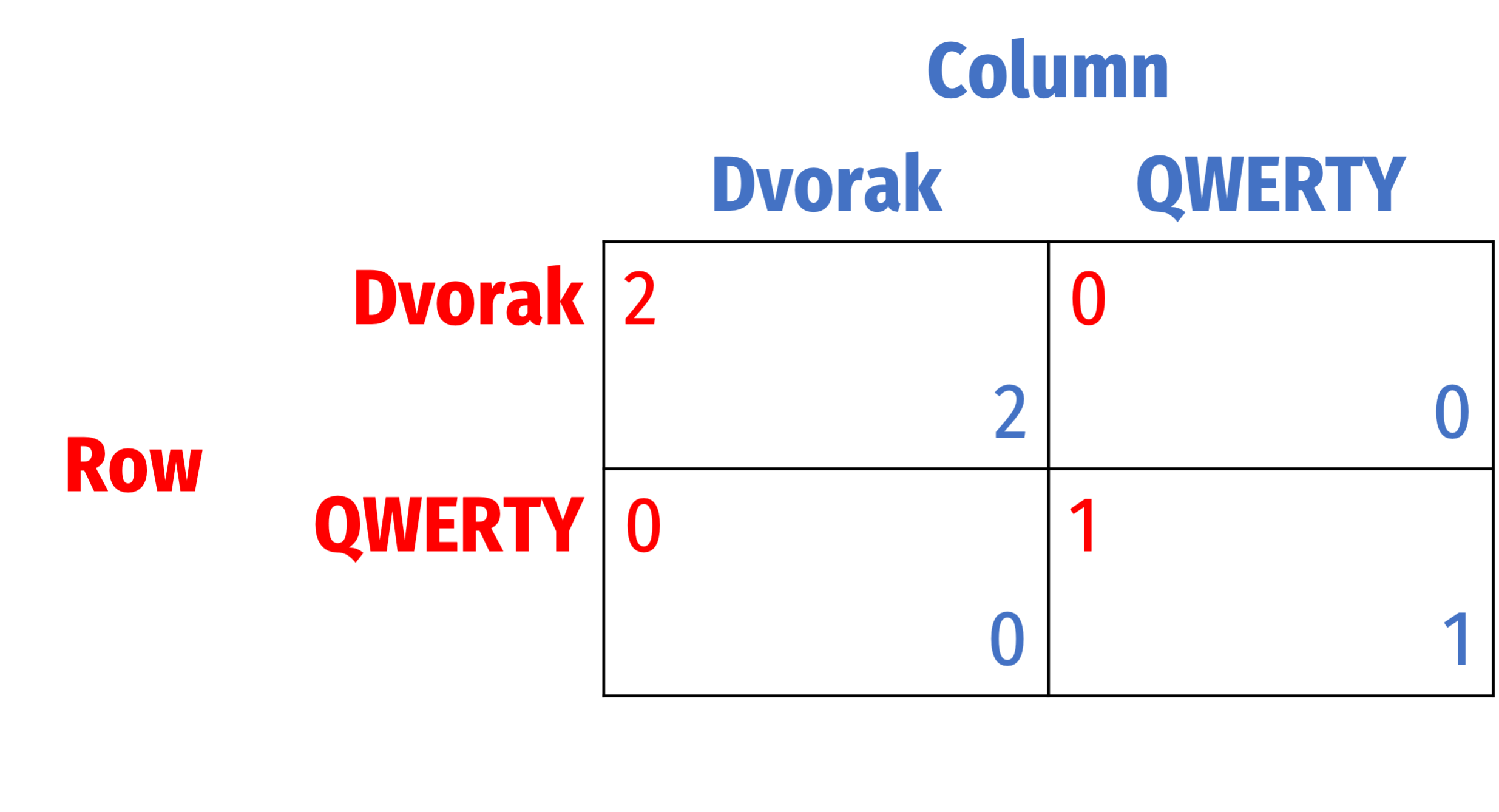

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

Suppose all agree Dvorak is superior

- But not guaranteed to be the outcome!

Path Dependence: early choices may affect later ability to choose or switch

Lock-in: the switching cost of moving from one equilibrium to another becomes prohibitive

David, Paul A, 1985, "Clio and the Economics of QWERTY," American Economic Review, 75(2):332-337

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

"First-degree" path dependency:

- Sensitivity to initial conditions

- But no inefficiency

Examples:

- language

- driving on left vs. right side of road

Liebowitz, Stan J and Stephen E Margolis, 1990, "The Fable of the Keys," Journal of Law and Economics, 33(1):1-25

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

"Second-degree" path dependency:

- Sensitivity to initial conditions

- Imperfect information at time of choice

- Outcomes are regrettable ex post

Not inefficient: no better decision could have been made at the time

Liebowitz, Stan J and Stephen E Margolis, 1990, "The Fable of the Keys," Journal of Law and Economics, 33(1):1-25

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

"Third-degree" path dependency:

- Sensitivity to initial conditions

- Worse choice made

- Avoidable mistake at the time

Inefficient lock-in

Liebowitz, Stan J and Stephen E Margolis, 1990, "The Fable of the Keys," Journal of Law and Economics, 33(1):1-25

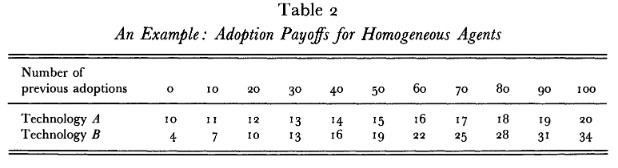

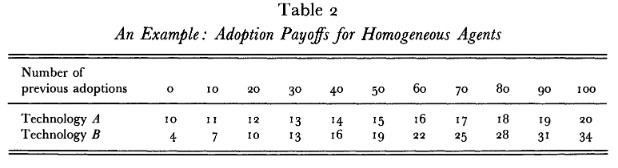

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

Arthur, W. Brian, 1989, "Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events," Economic Journal 99(394): 116-131

In the long-run, Technology B is superior

But in the short-run, Technology A has higher payoffs

Inefficient lock-in

But what about uncertainty?

- What set of institutions will choose best under uncertainty?

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

Arthur, W. Brian, 1989, "Competing Technologies, Increasing Returns, and Lock-In by Historical Events," Economic Journal 99(394): 116-131

Role for entrepreneurial judgment and "championing" a standard

- Someone who "owns" a standard has strong incentive to see it adopted

Champions who forecast higher long-term payoffs can subsidize adoption in the short run

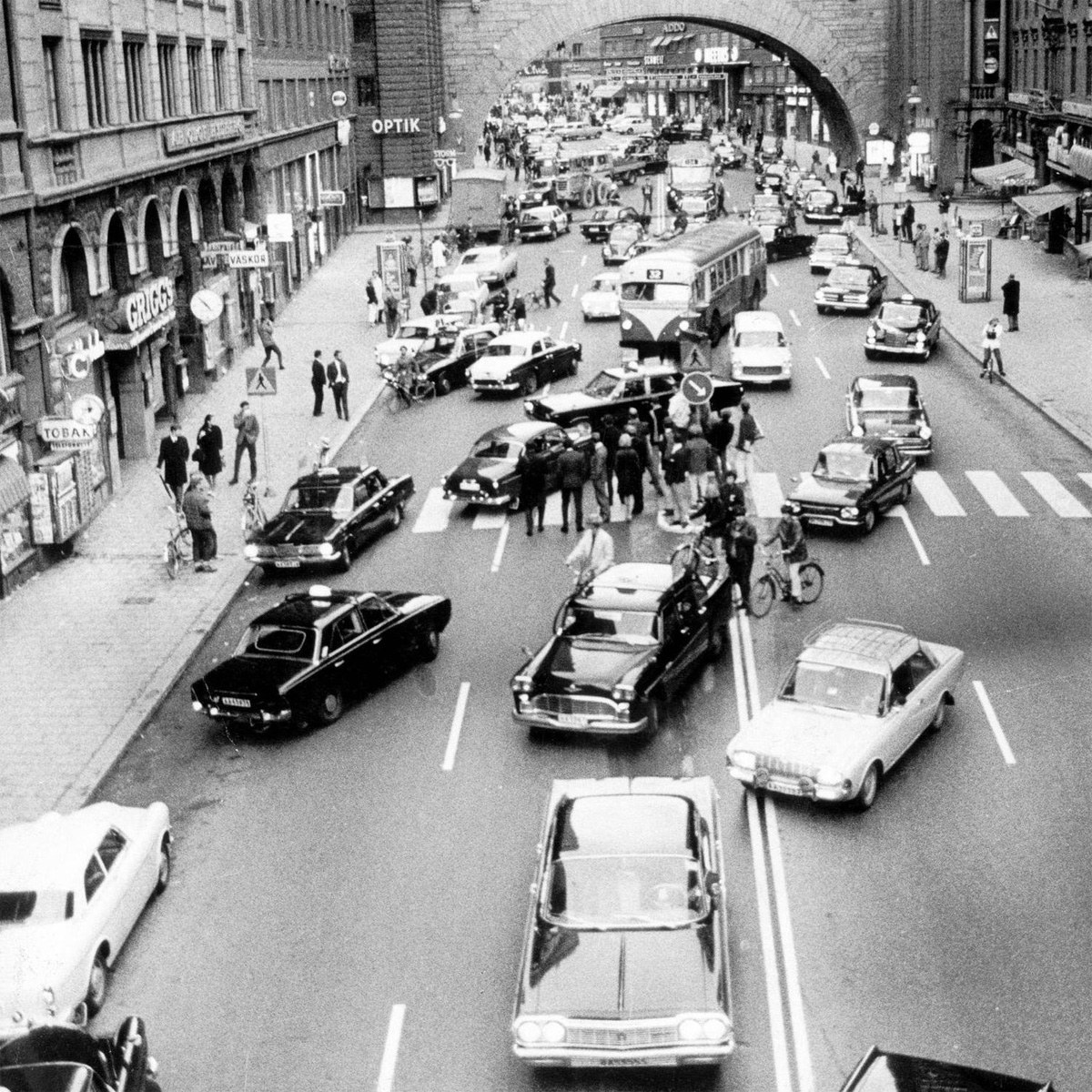

Assurance Games: Path Dependence & Lock-In

September 3, 1967, “H day” in Sweden

- Högertrafikomläggningen: “right-hand traffic diversion”

Sweden switched from driving on the left side of the road to the right

- Both of Sweden’s neighbors drove on the right, 5 million vehicles/year crossing borders

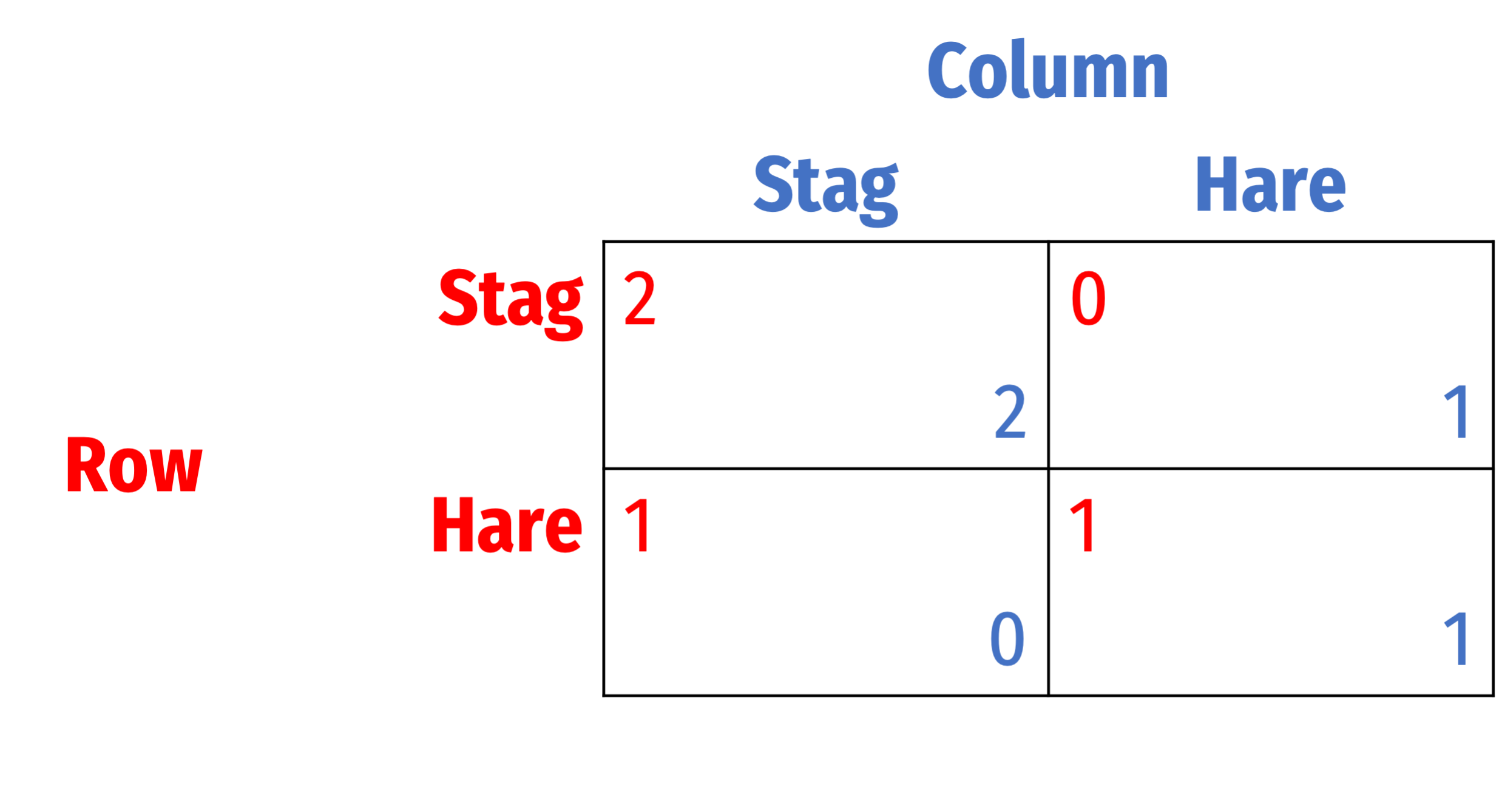

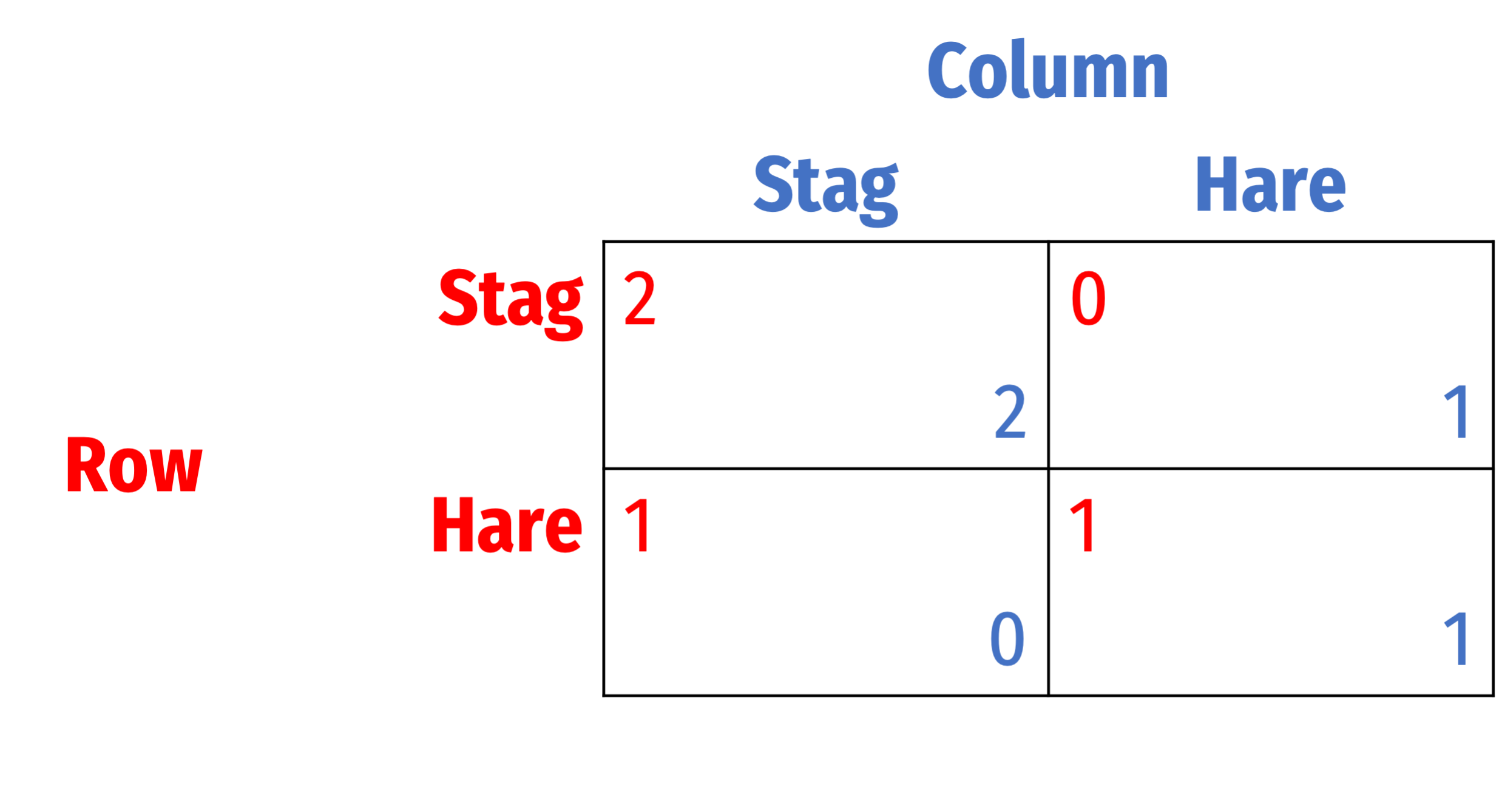

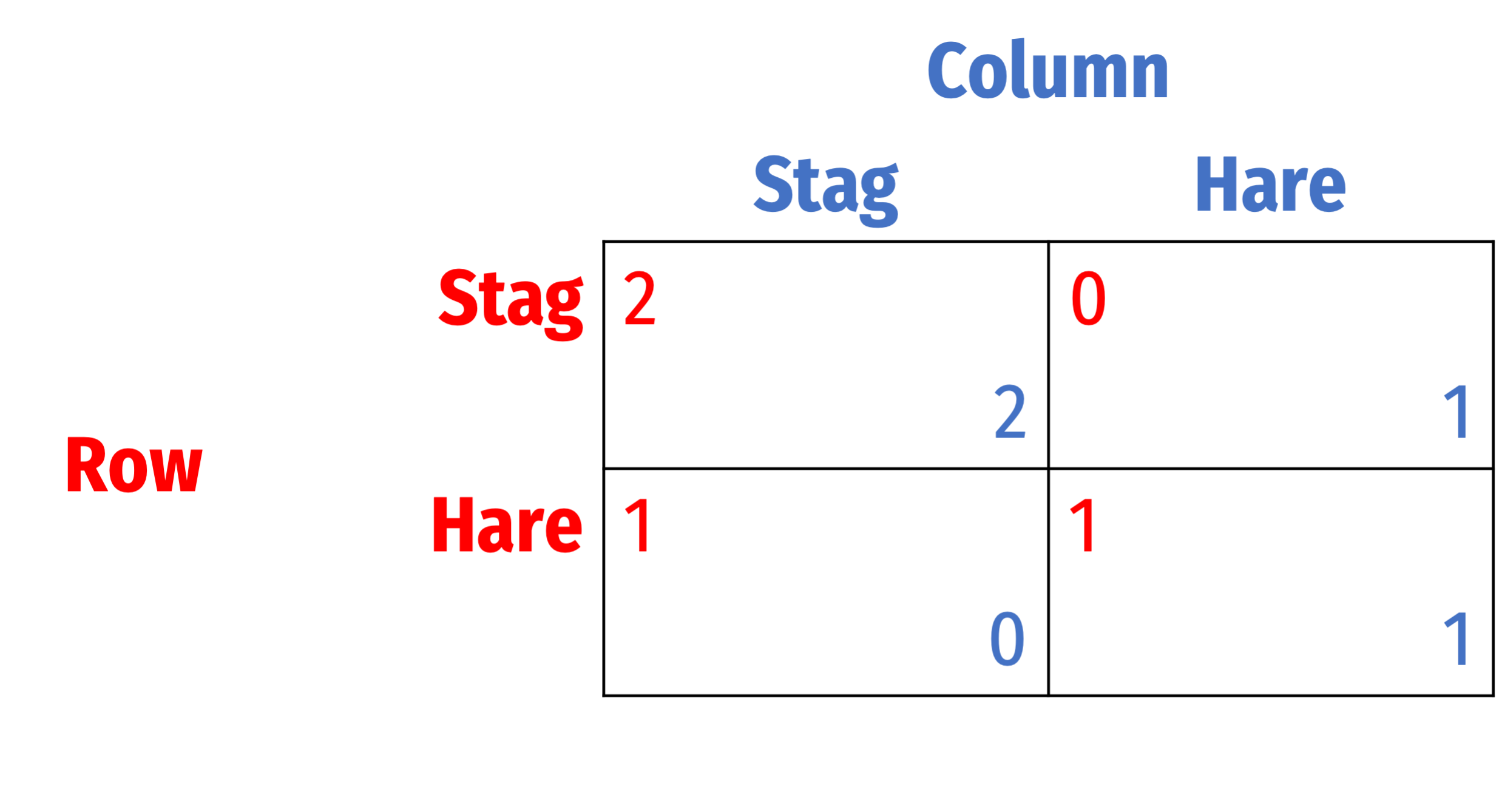

Assurance Games: Stag Hunt

- Famous variant: the “Stag Hunt”

“If it was a matter of hunting a deer, everyone well realized that he must remain faithful to his post; but if a hare happened to pass within reach of one of them, we cannot doubt that he would have gone off in pursuit without scruple.”

rousseau, Jean Jacques, 1754, Discourse of Inequality

Assurance Games: Stag Hunt

Often invoked to discuss public goods, free rider problems

Two PSNE, and (Stag, Stag) ≻ (Hare, Hare)

Can't take down a Stag alone, need to rely on a group to work together

- But unlike prisoners' dilemma, no incentive to overtly “screw over” the group

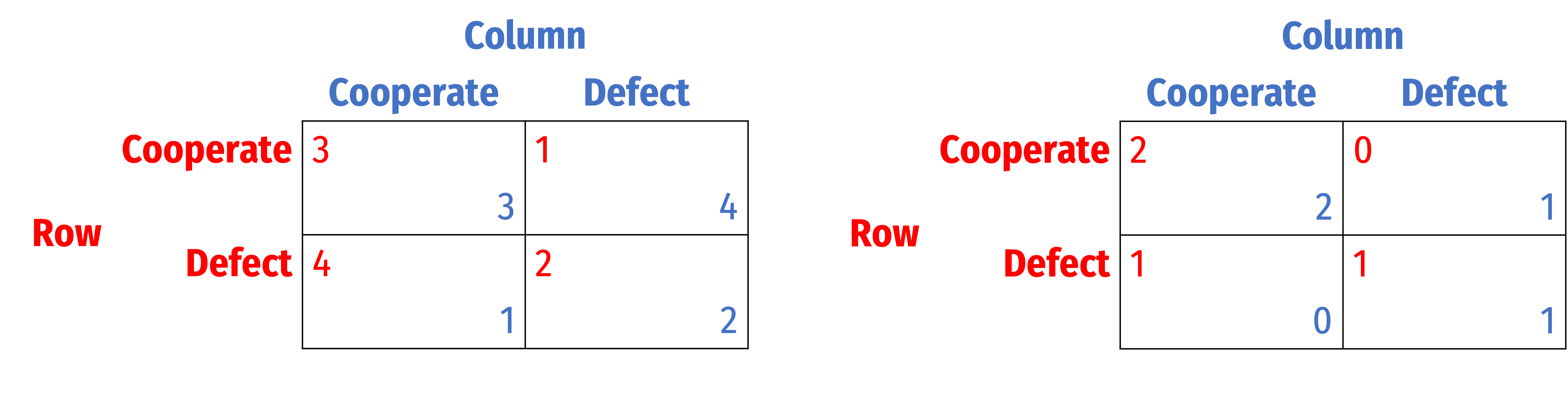

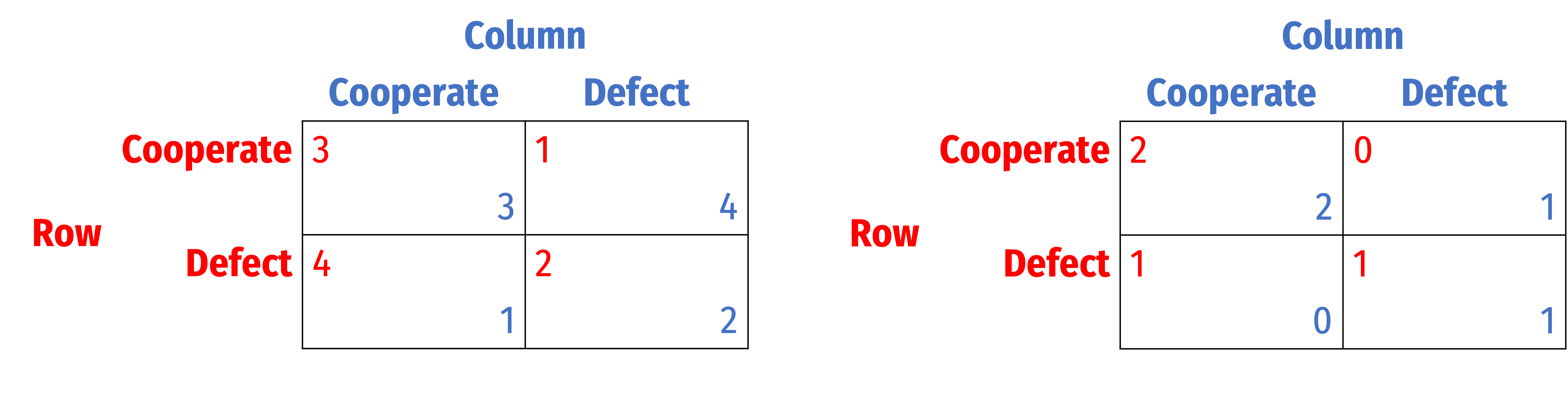

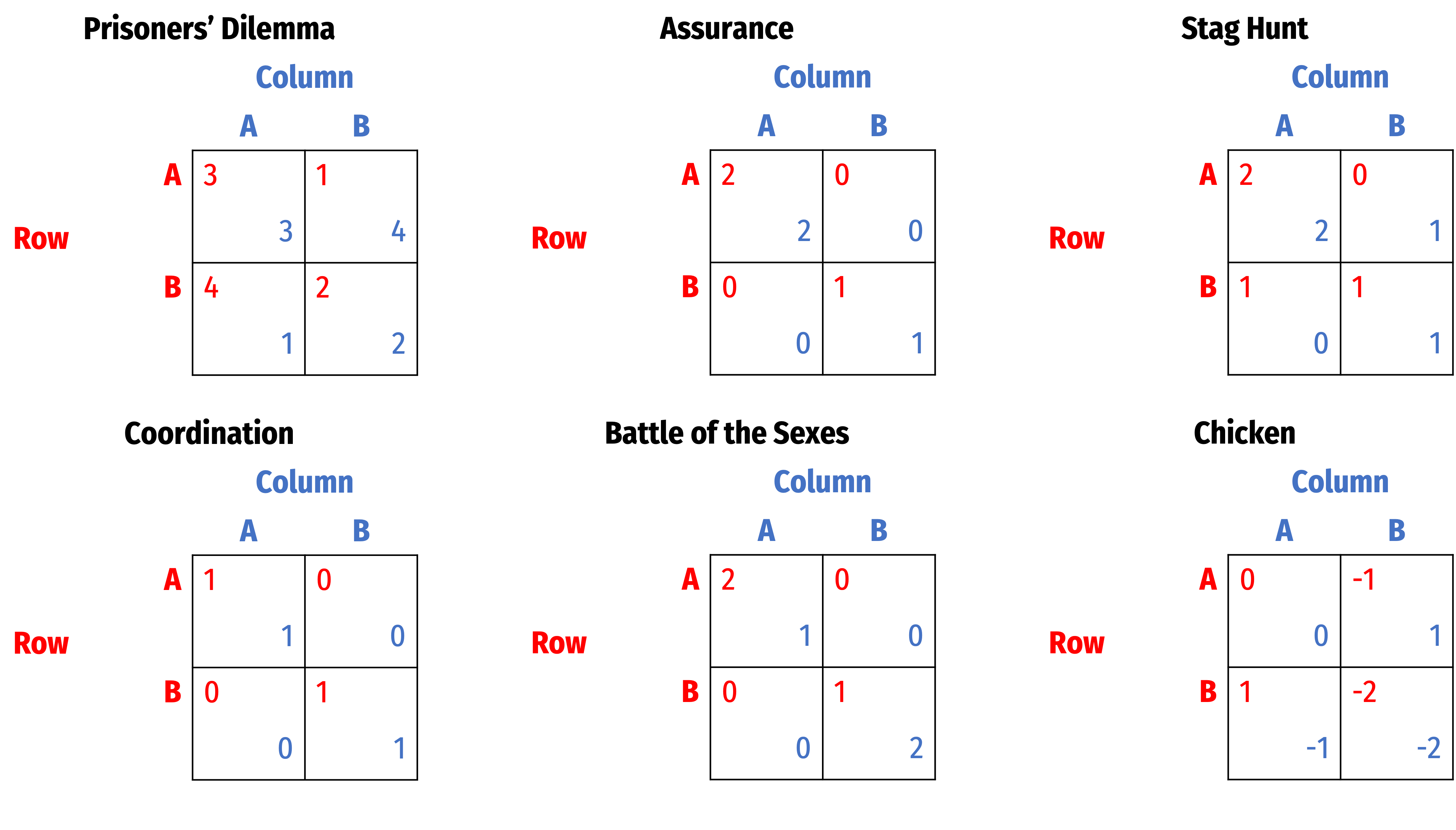

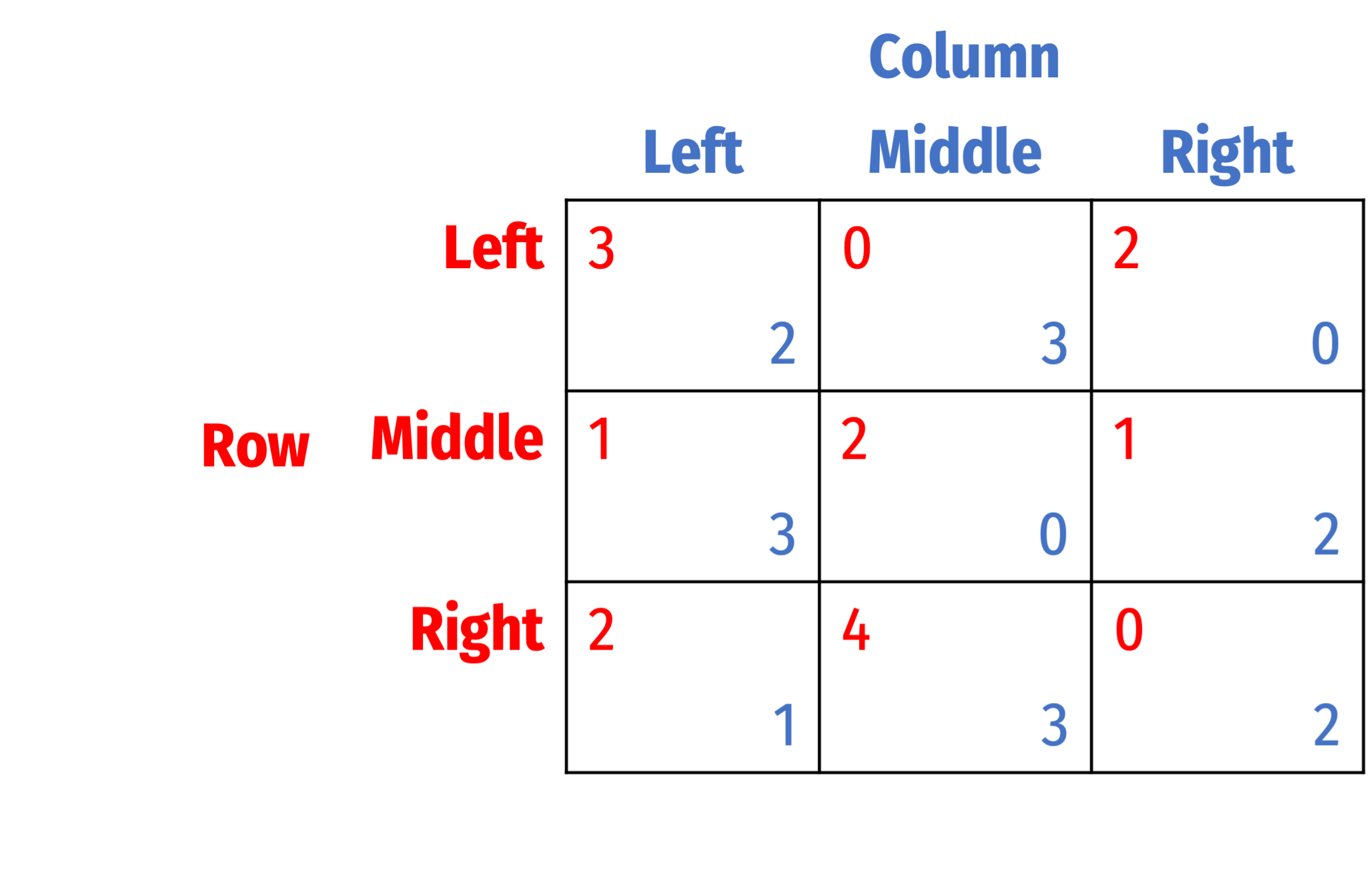

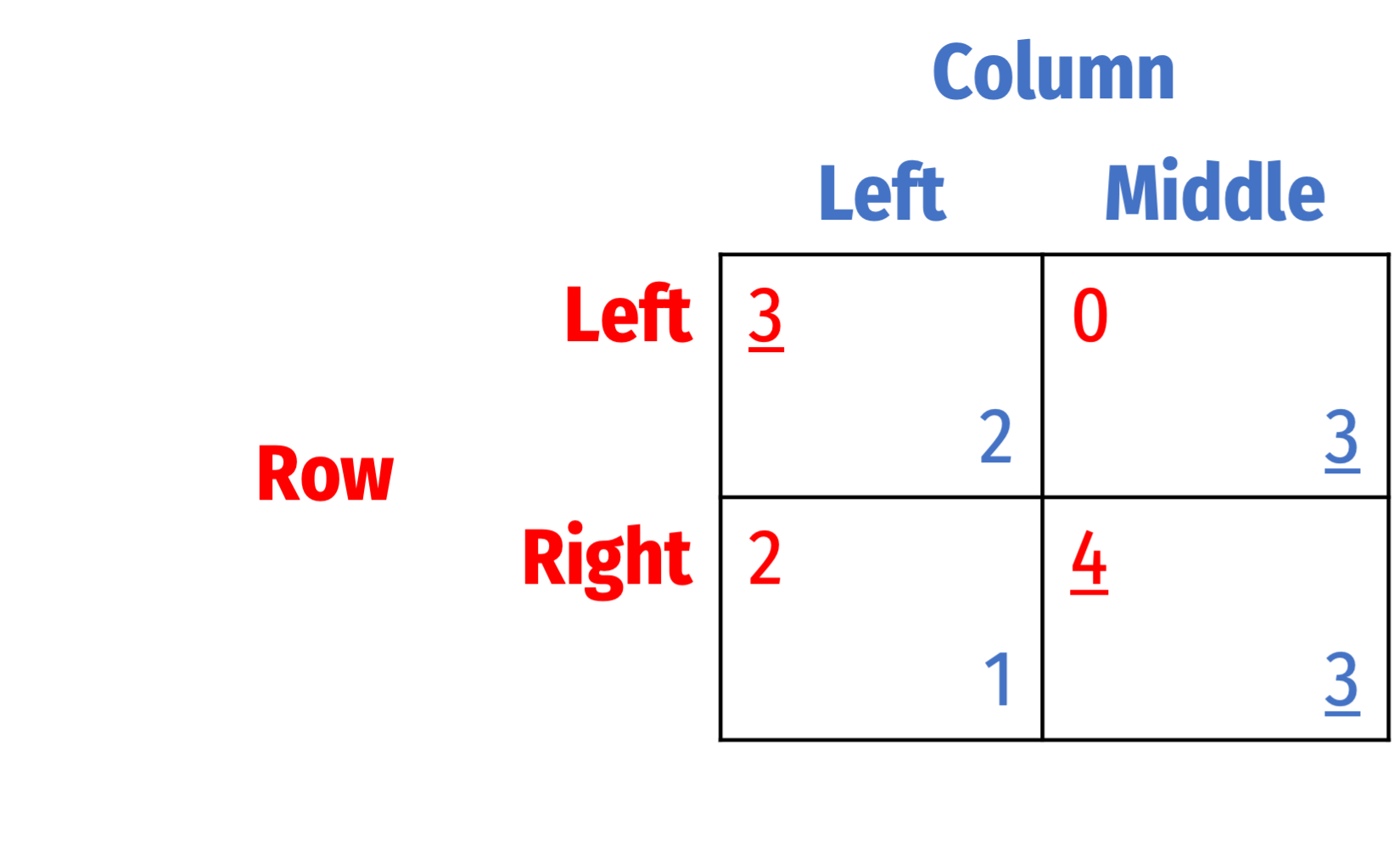

Prisoners' Dilemma vs. Assurance/Stag Hunt

Prisoners' Dilemma vs. Assurance/Stag Hunt

- Dominant strategy to always Defect

- Nash equilibrium: (Defect, Defect)

- (Coop, Coop) ≻ (Defect, Defect)

- (Coop, Coop) not a Nash equilibrium

- No dominant or dominated strategies

- 2 NE: (Coop, Coop) and (Defect, Defect)

- (Coop, Coop) ≻ (Defect, Defect)

- Can get stuck in (Defect, Defect) but (Coop, Coop) is stable & possible

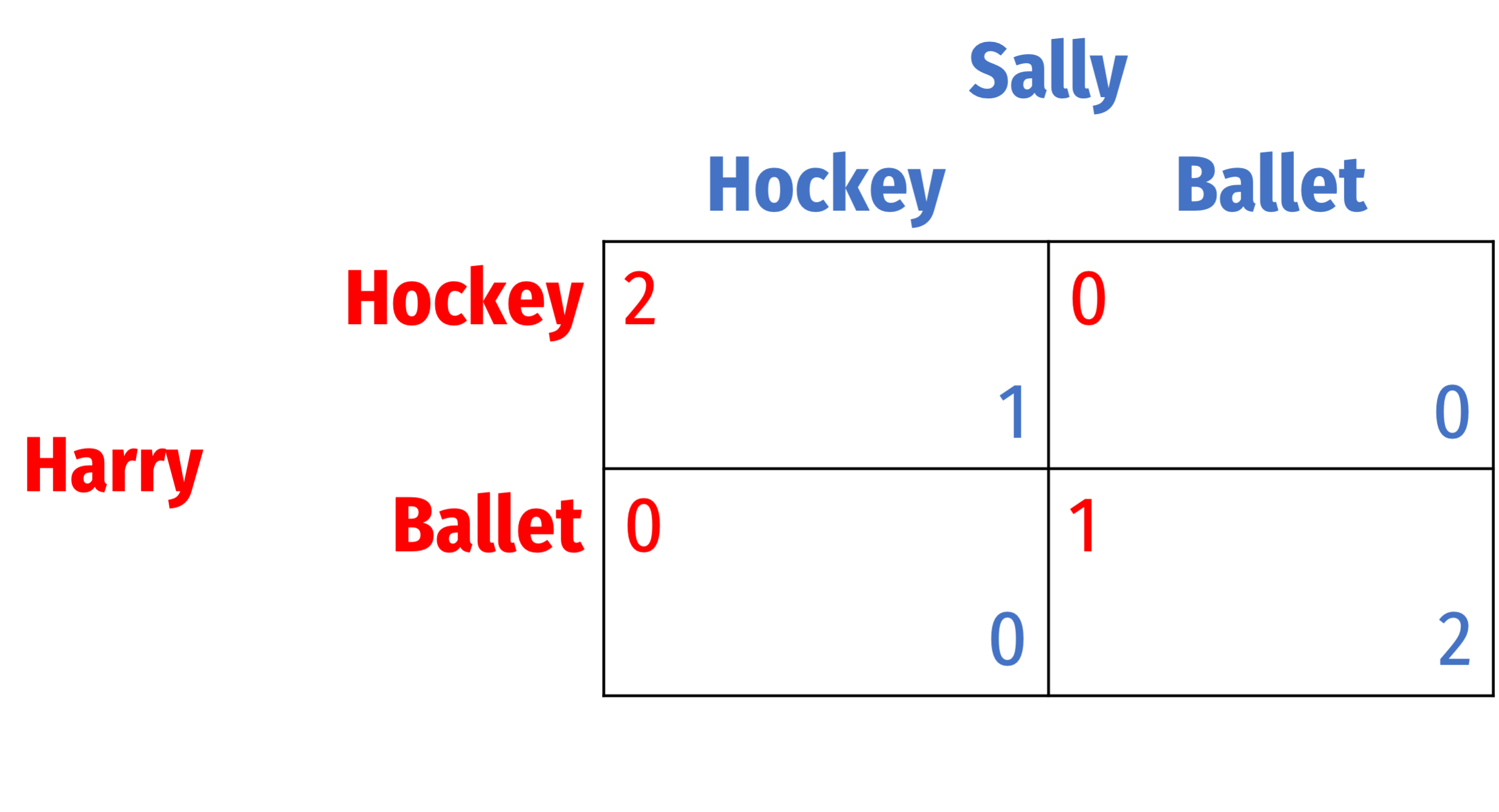

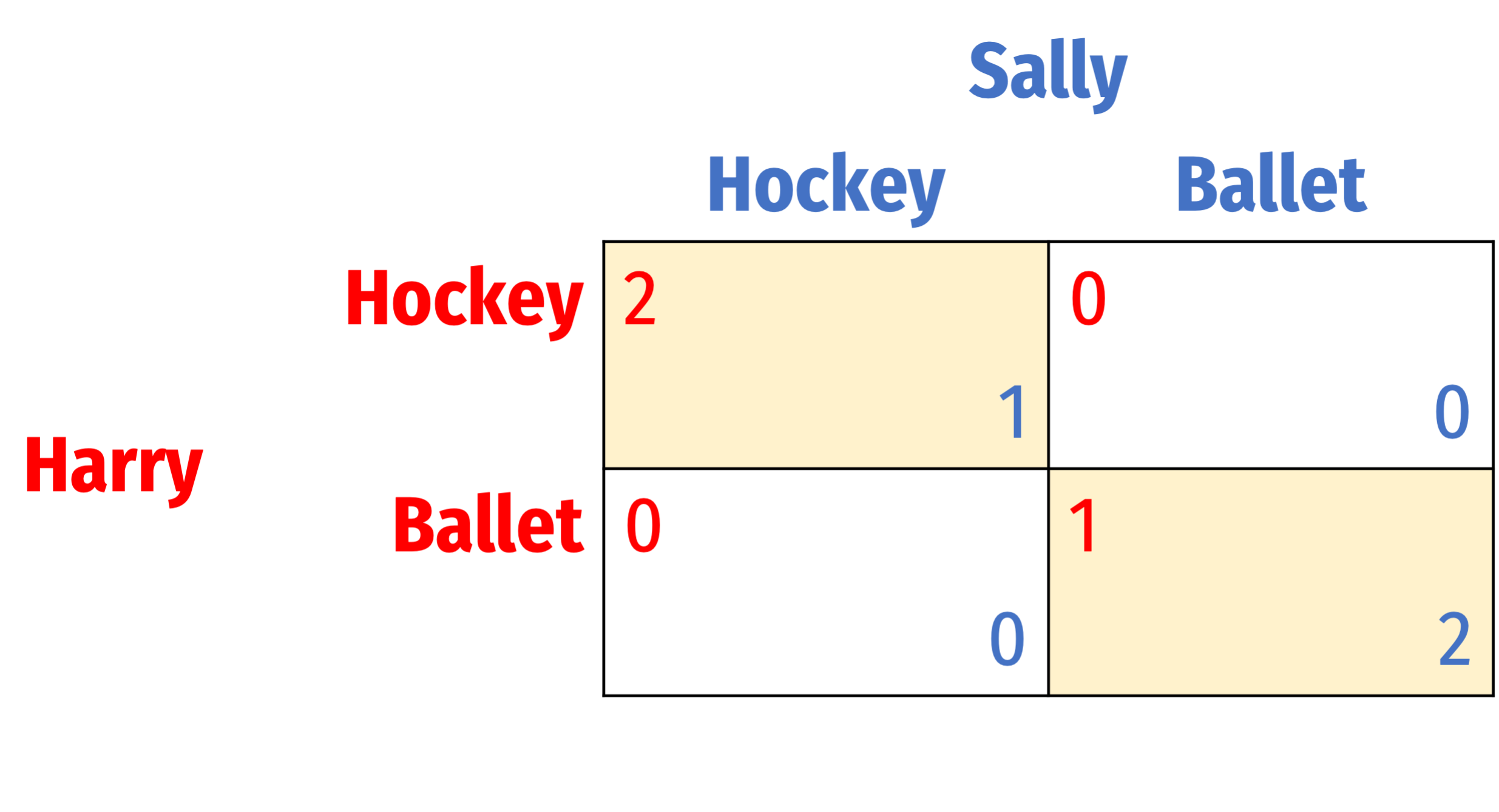

Battle of the Sexes

Each player prefers a different Nash equilibrium over another

But coordinating is better than not-coordinating, for both!

Battle of the Sexes

Each player prefers a different Nash equilibrium over another

But coordinating is better than not-coordinating, for both!

Two PSNE:

- (Hockey, Hockey) — Harry's preference

- (Ballet, Ballet) — Sally's preference

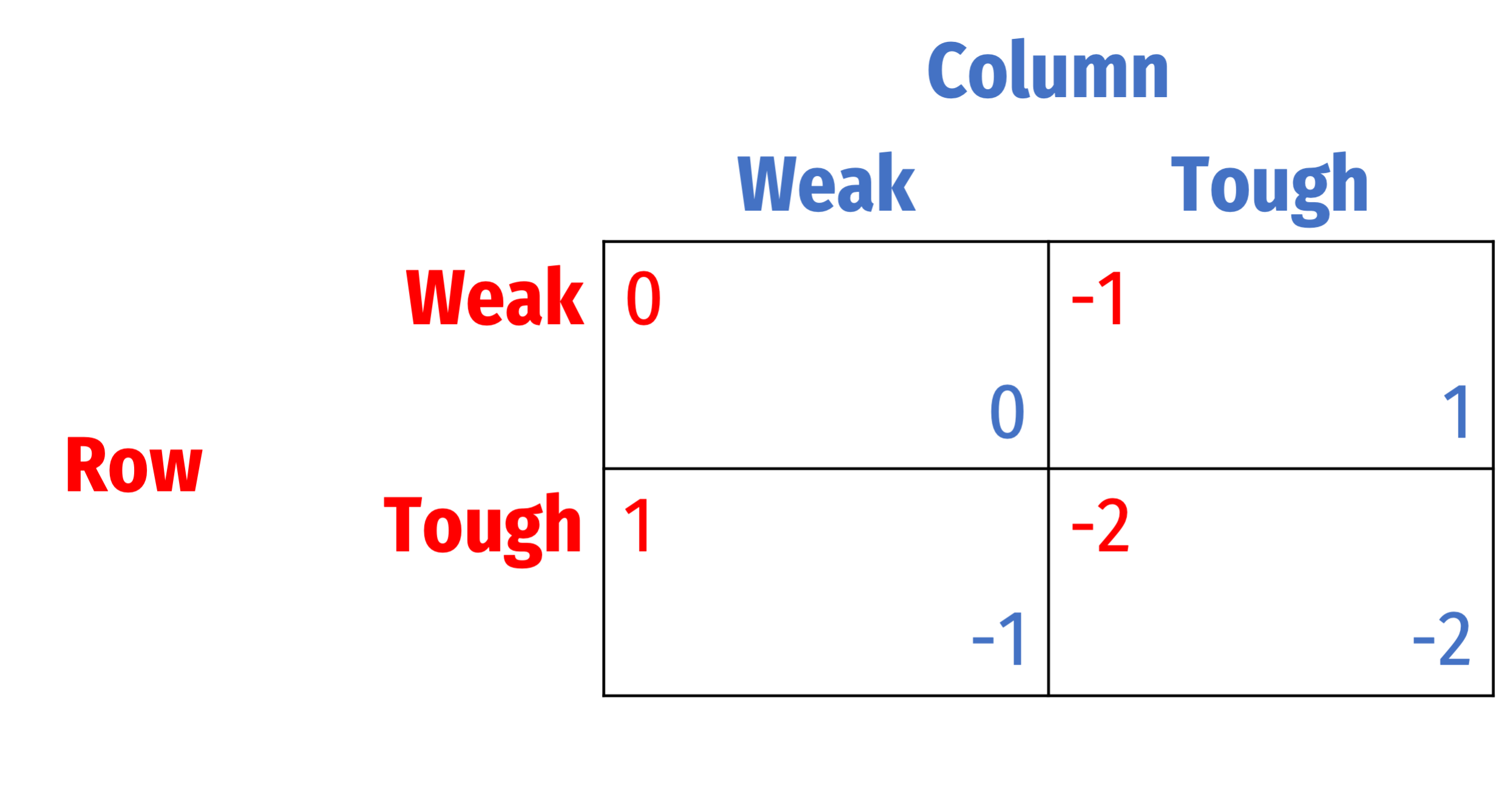

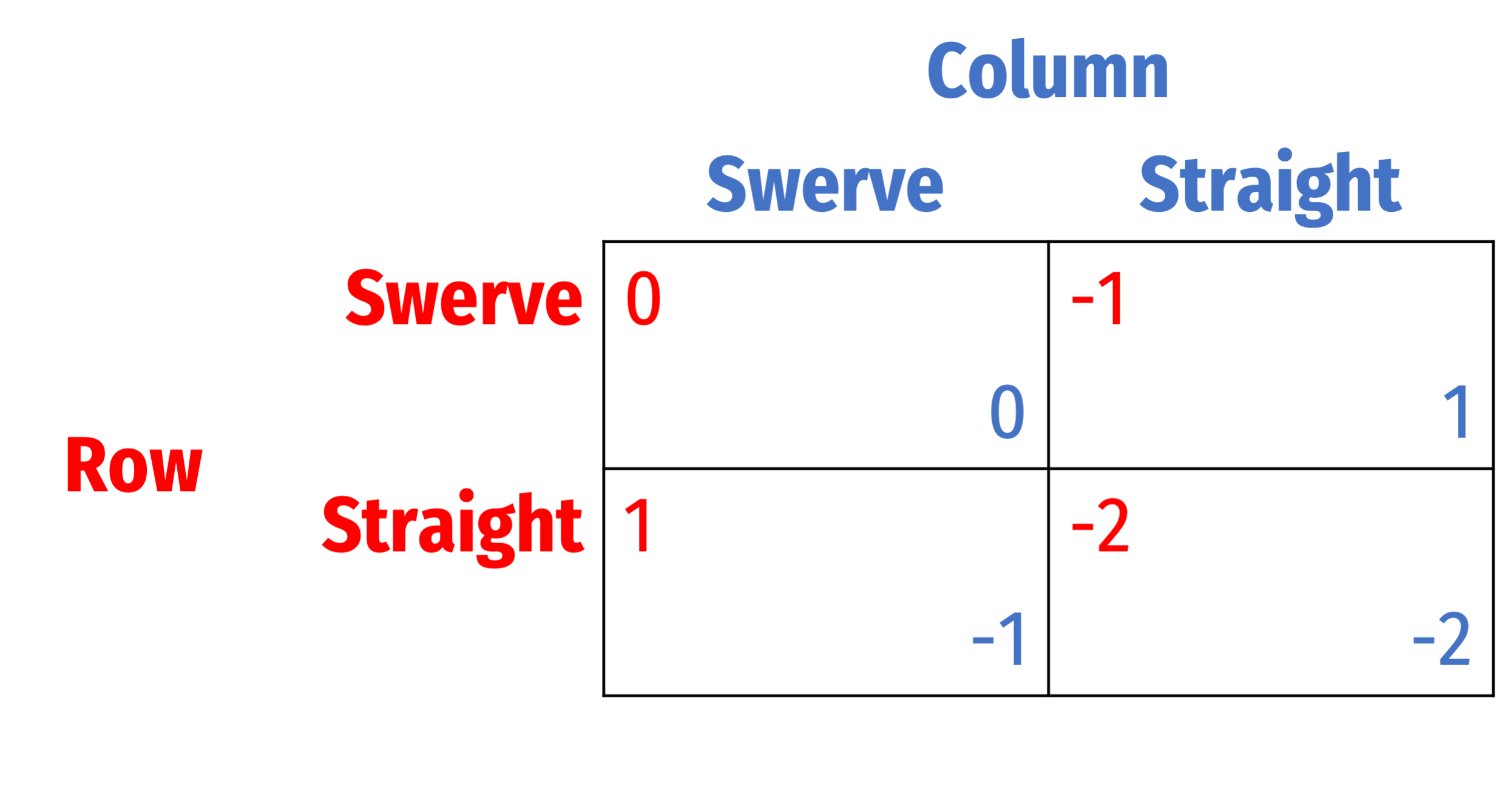

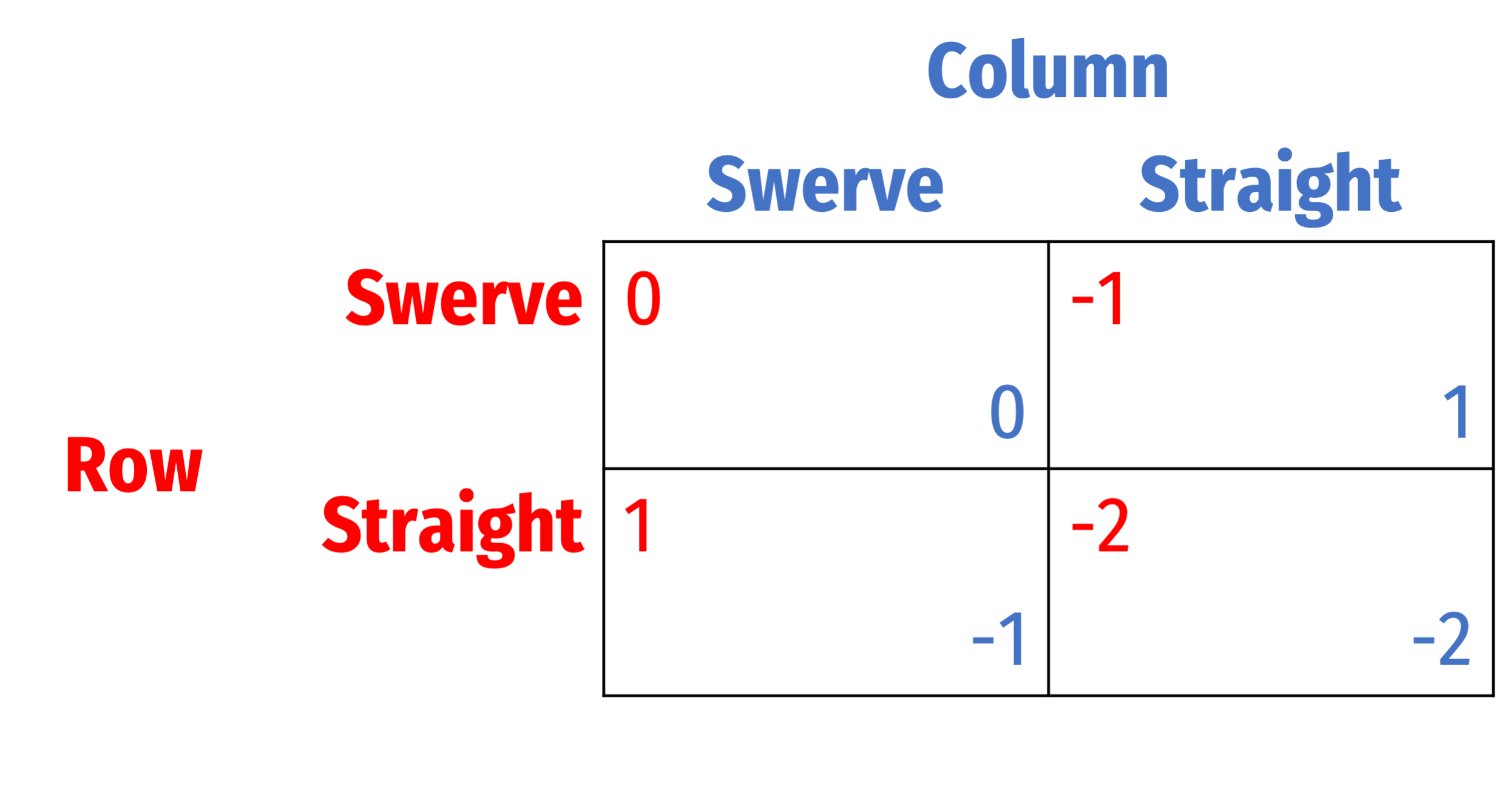

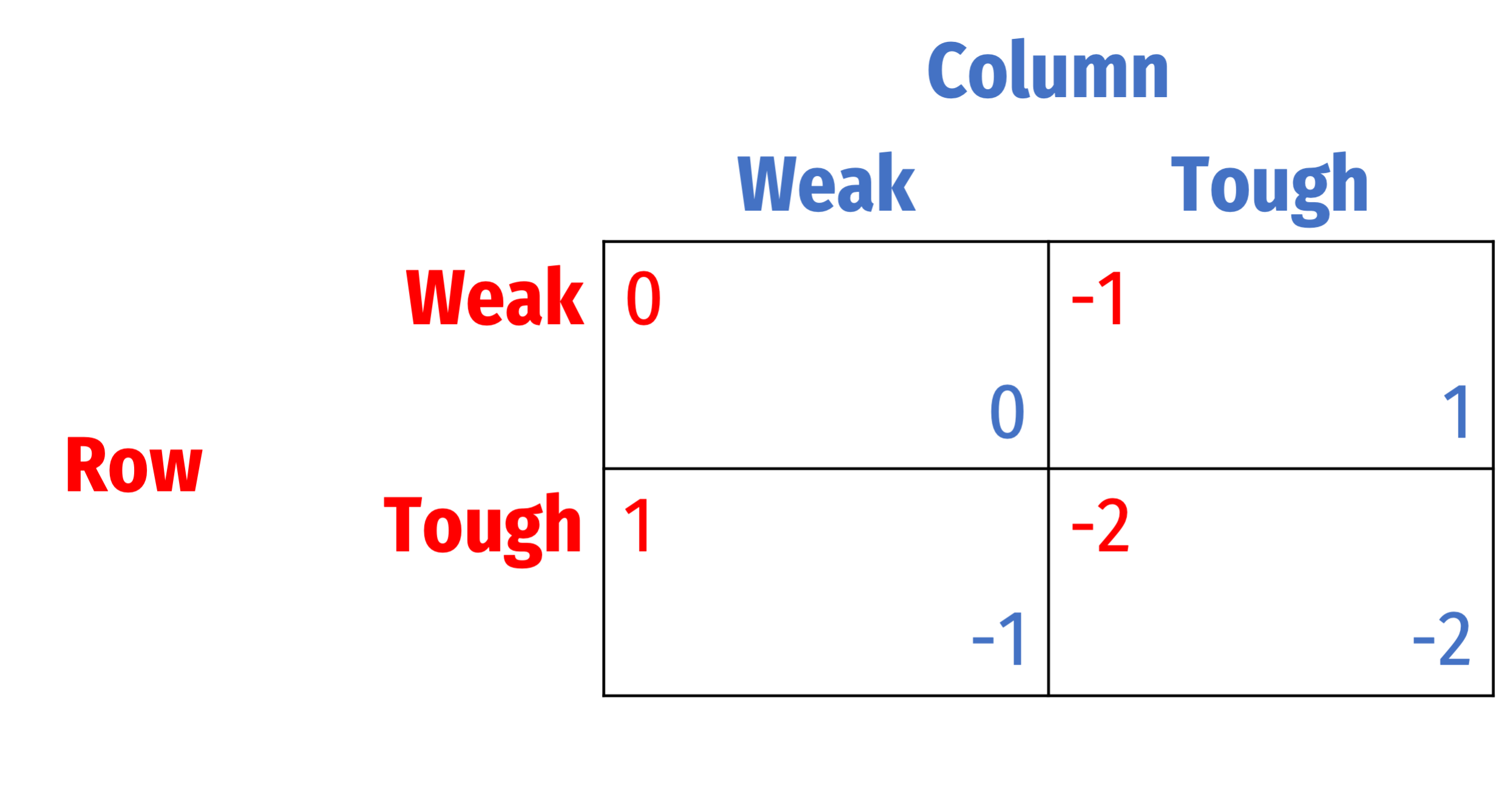

Chicken

Two strategies per player: act tough/cool vs. weak

Each prefers to act tough and have the other player act weak

- But if both act tough, the worst outcome for both

Often called an “anti-coordination” game

Chicken

A common example in movies

Two cars aimed at each other, or racing furthest to edge of cliff

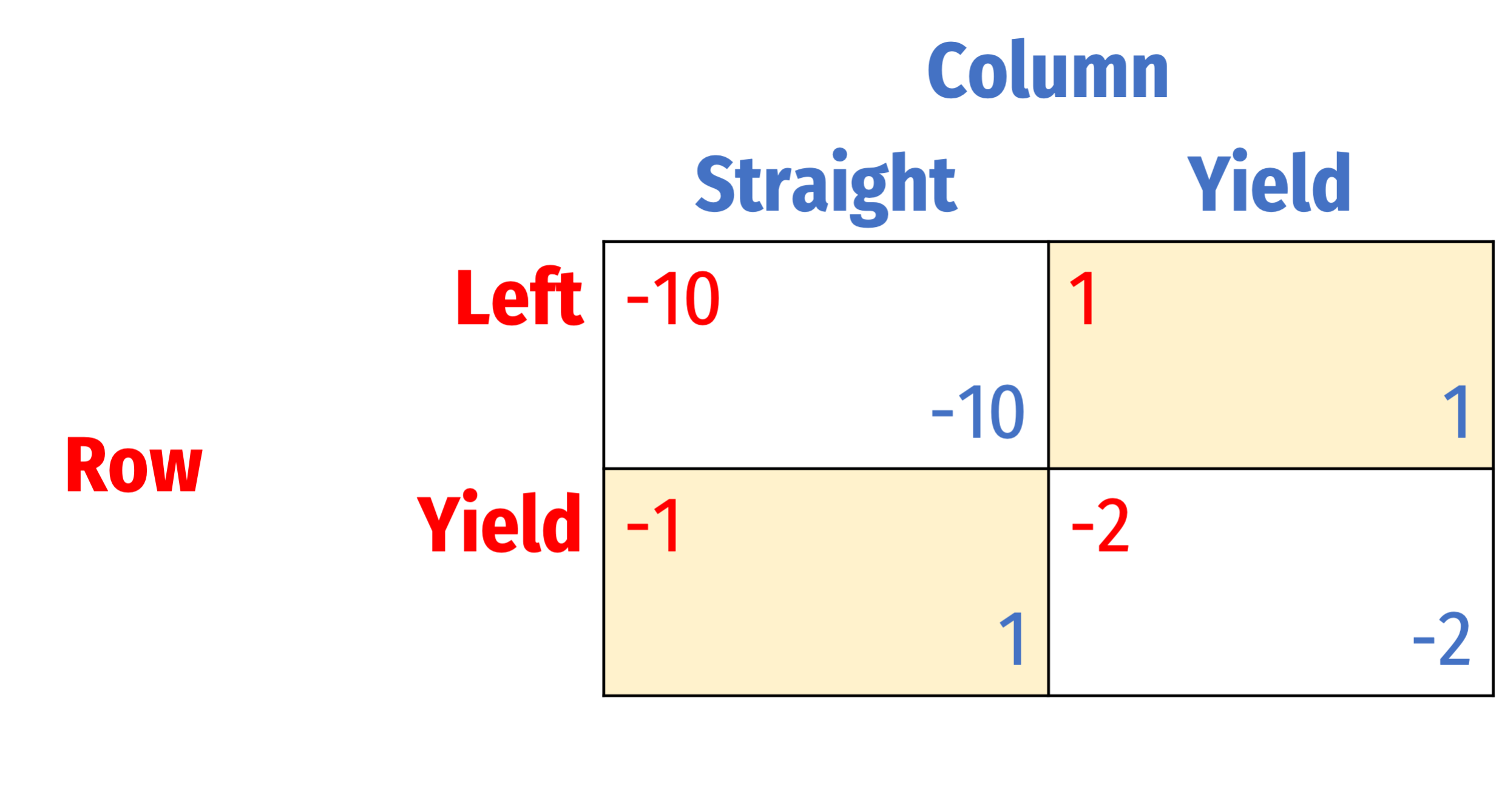

Chicken

A common example in movies

Two cars aimed at each other, or racing furthest to edge of cliff

Two PSNE:

- (Straight, Swerve) — Row's preference

- (Swerve, Straight) — Column's preference

So long as both choose different strategies, avoids worst outcome

Chicken

Chicken

Chicken and Commitment

Each player may try to influence the game beforehand

Project and signal “toughness” (or that they are “crazy”) before the game

Find a commitment strategy so you have no choice but to play tough

- e.g. rip out the steering wheel!

Schelling: “If you're invited to play chicken and you decline, you've already played [and lost]”

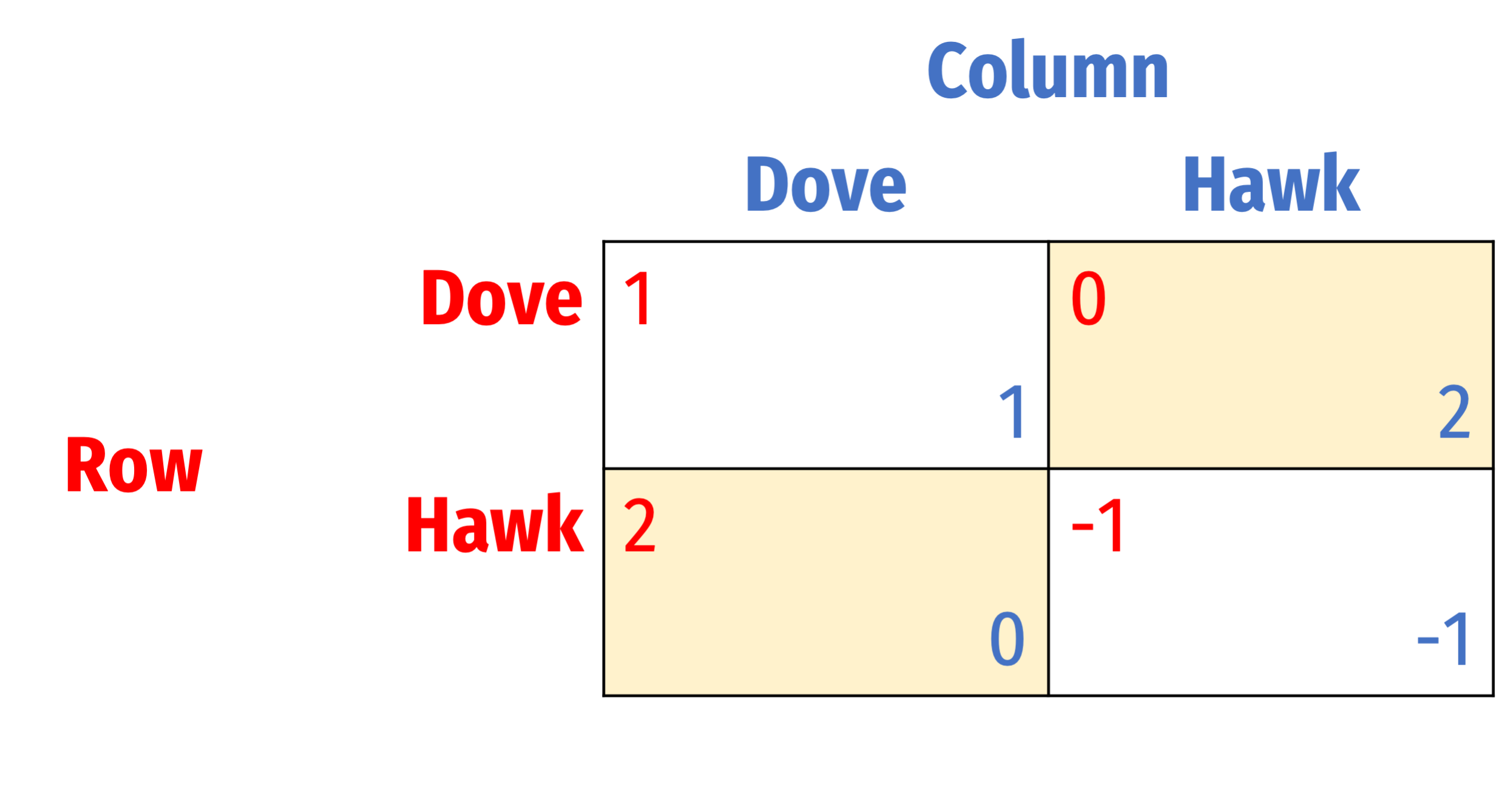

Chicken: Hawk Dove

One variant of chicken is also famous: Hawk-Dove game

- (actually, chicken is just a special case of hawk dove!)

Evolutionary biology, political science, bargaining

Game Types

Modeling Social Interactions

Can all players potentially benefit from the interaction?

- No: chicken

Do all players prefer one outcome over another?

- Yes: assurance game

Does the players prefer different outcomes?

- Yes: battle of the sexes

Is there a Pareto improvement from Nash equilibrium?

- Yes: assurance game

- Yes, but it's not a NE: prisoners' dilemma

Multiple Equilibria

Multiple Equilibria: What to Do?

Nash equilibrium is the most well known solution concept in game theory

- Method of predicting the outcome of a game

Suppose we have a coordination game with multiple equilibria

What can we say about behavior of players?

Multiple Equilibria: What to Do?

- One answer: nothing!

- Both equilibria are mutual best responses

- Coordination problem on which strategy to jointly select

- Two sides of the road to drive on, no one side better than the other

Multiple Equilibria: What to Do?

Another answer: we must confront multiple equilibria in economics

- still want to predict which outcome will occur

We need to consider multiple criteria beyond best responses to select a plausible equilibrium

- Focalness/salience

- Fairness/envy-free-ness

- Efficiency/payoff dominance

- Risk dominance

Multiple Equilibria: Efficiency

Which equilibrium is most (Pareto) efficient?

- Must be no other equilibrium where at least one player earns a higher payoff and no player earns a lower payoff

Stag Hunt:

- Both (Stag, Stag) and (Hare, Hare) are Nash equilibria

- (Stag, Stag) is Pareto superior to (Hare, Hare)

Multiple Equilibria: Efficiency

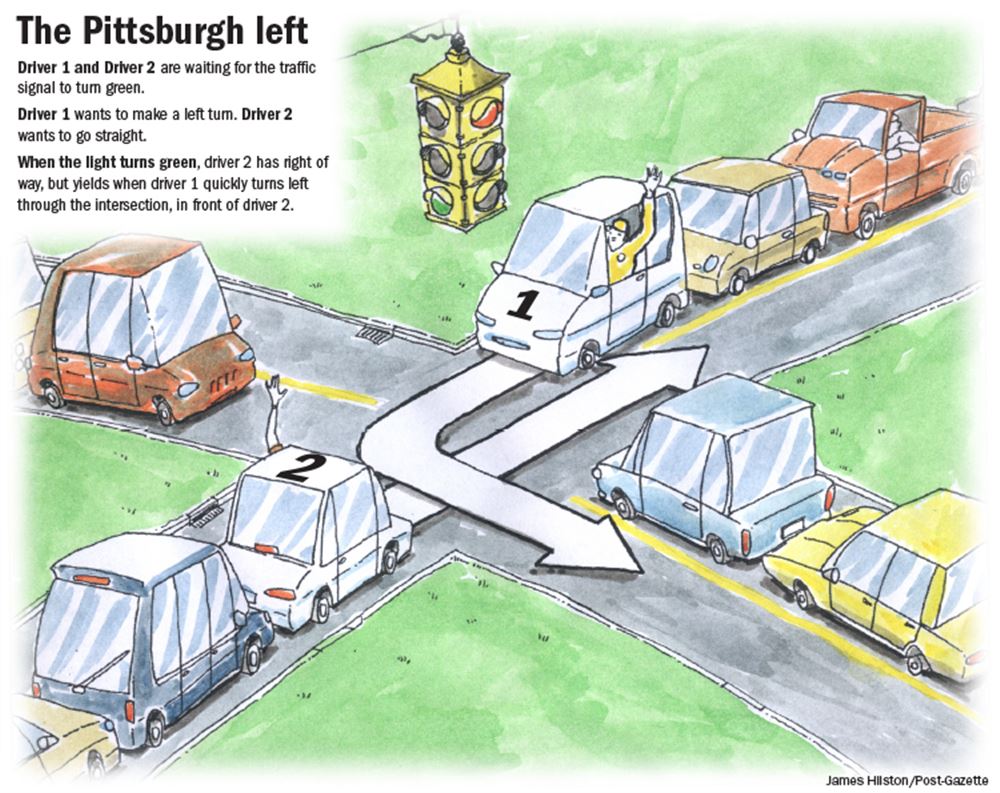

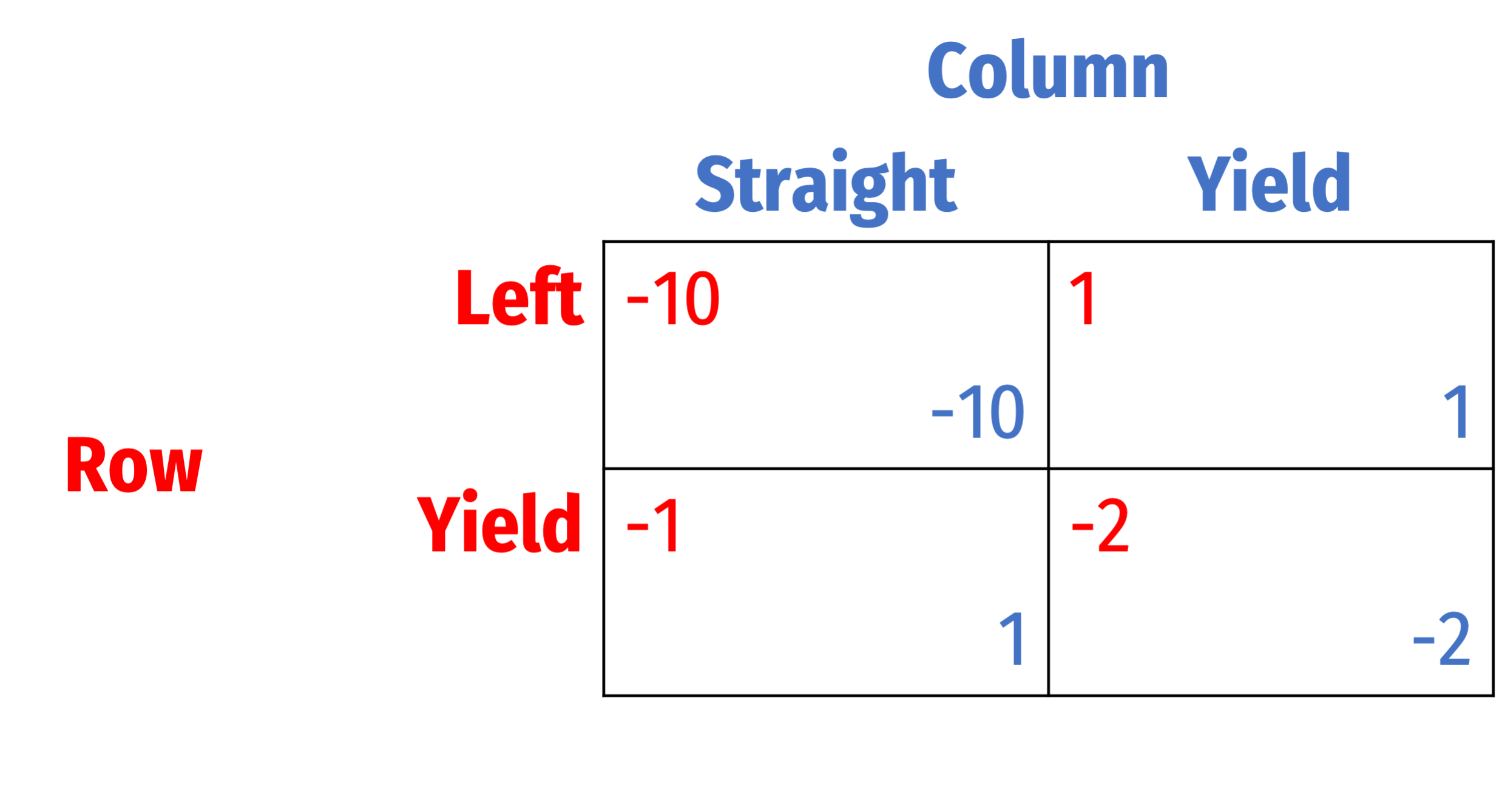

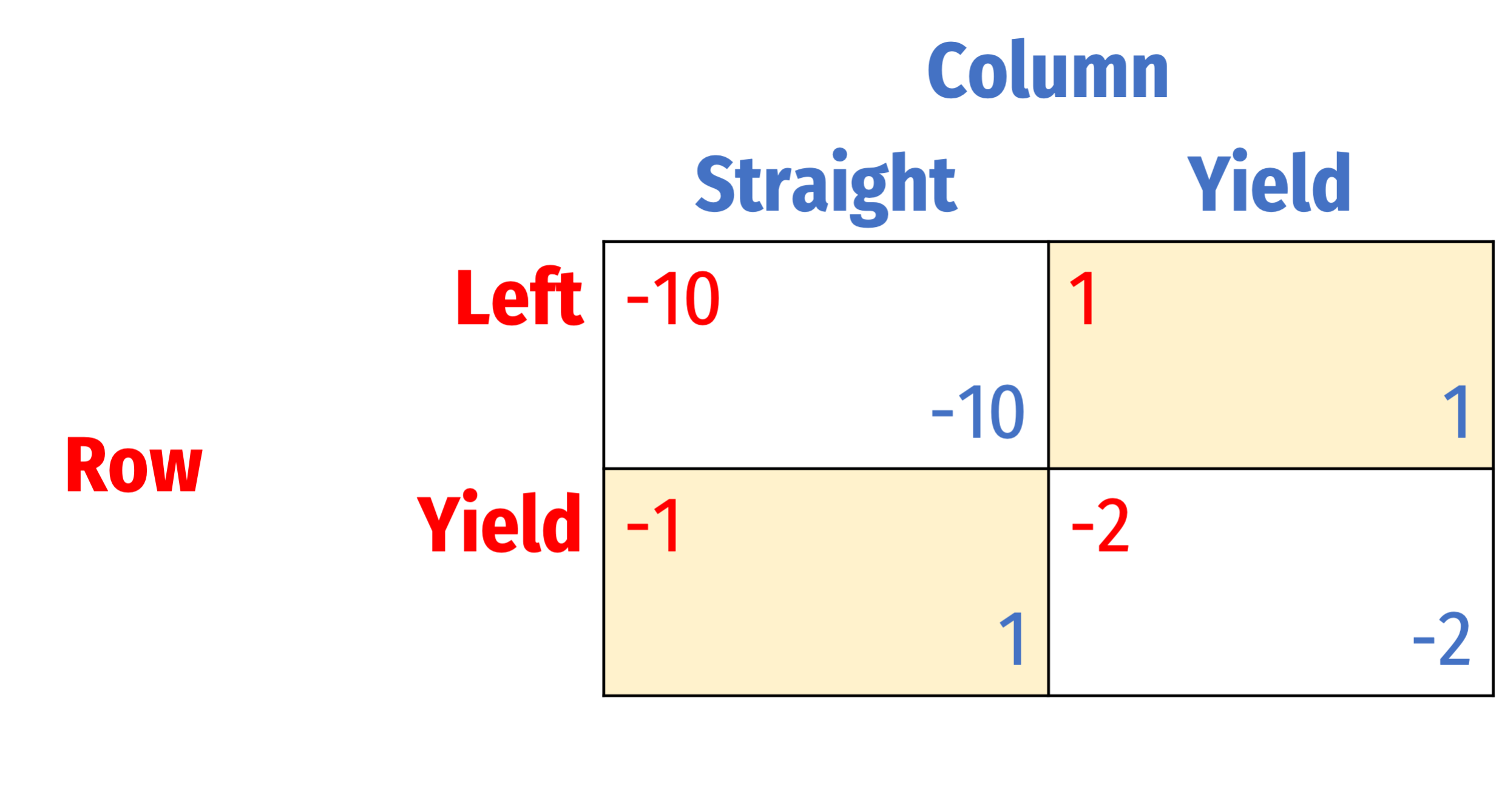

- Consider the “Pittsburgh Left” game

Multiple Equilibria: Efficiency

Consider the “Pittsburgh Left” game

Two PSNE: (Left, Yield) and (Yield, Straight)

- Each driver prefers that the other yield

This is just a variant of Chicken

Both equilibria are Pareto efficient!

Multiple Equilibria: Efficiency

We often face multiple Pareto efficient equilibria

Sometimes institutions are created to select and enforce a particular equilibrium

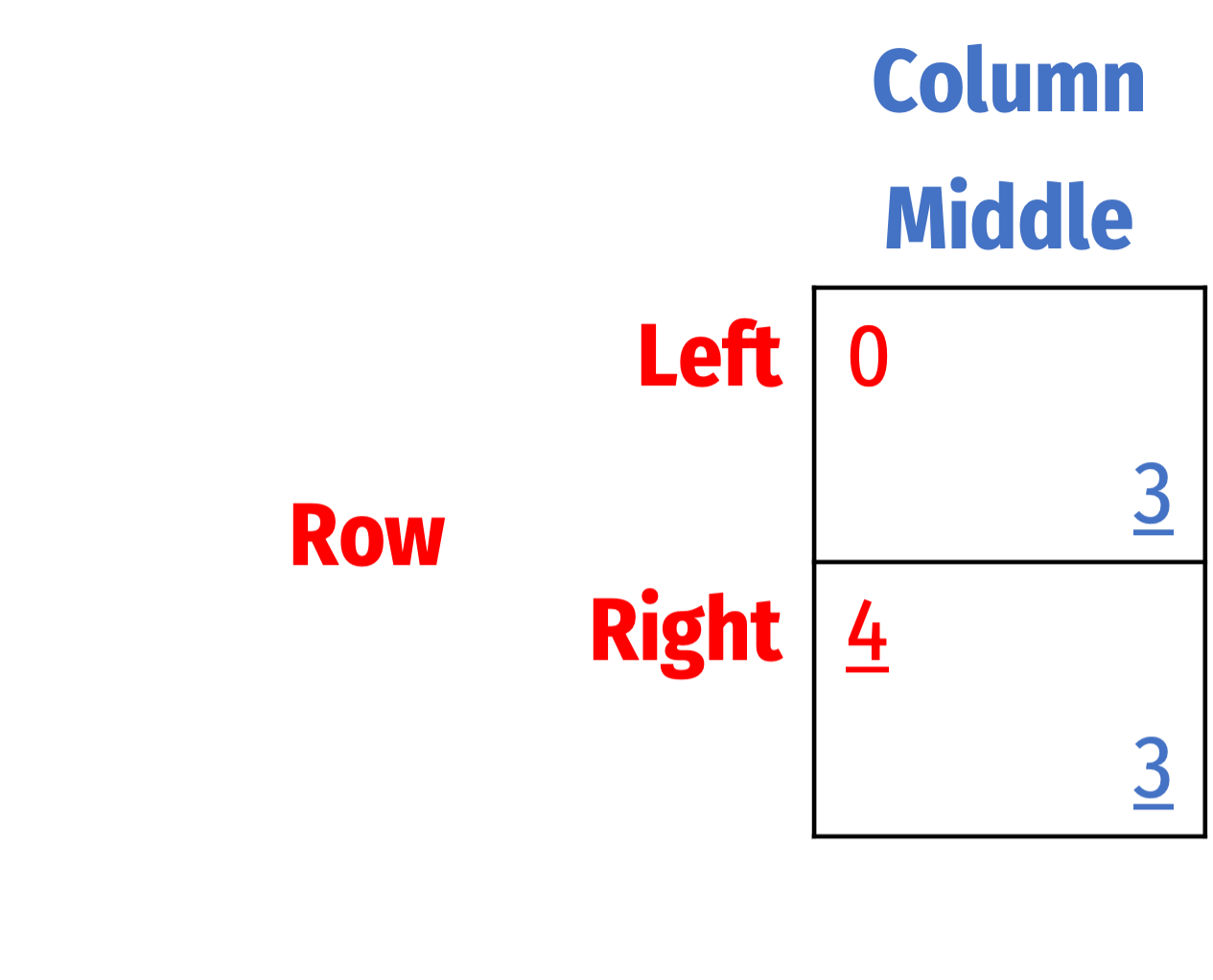

Multiple Equilibria: Risk Dominance

Consider a Stag Hunt

(Stag, Stag) is efficient and “payoff dominant”

- Highest payoff for each player, no possible Pareto improvement

(Hare, Hare) is “risk dominant”

- A less-risky equilibrium

- By playing Hare, each player guarantees themself 1 regardless of other player's strategy

Rationalizability & the Role of Beliefs

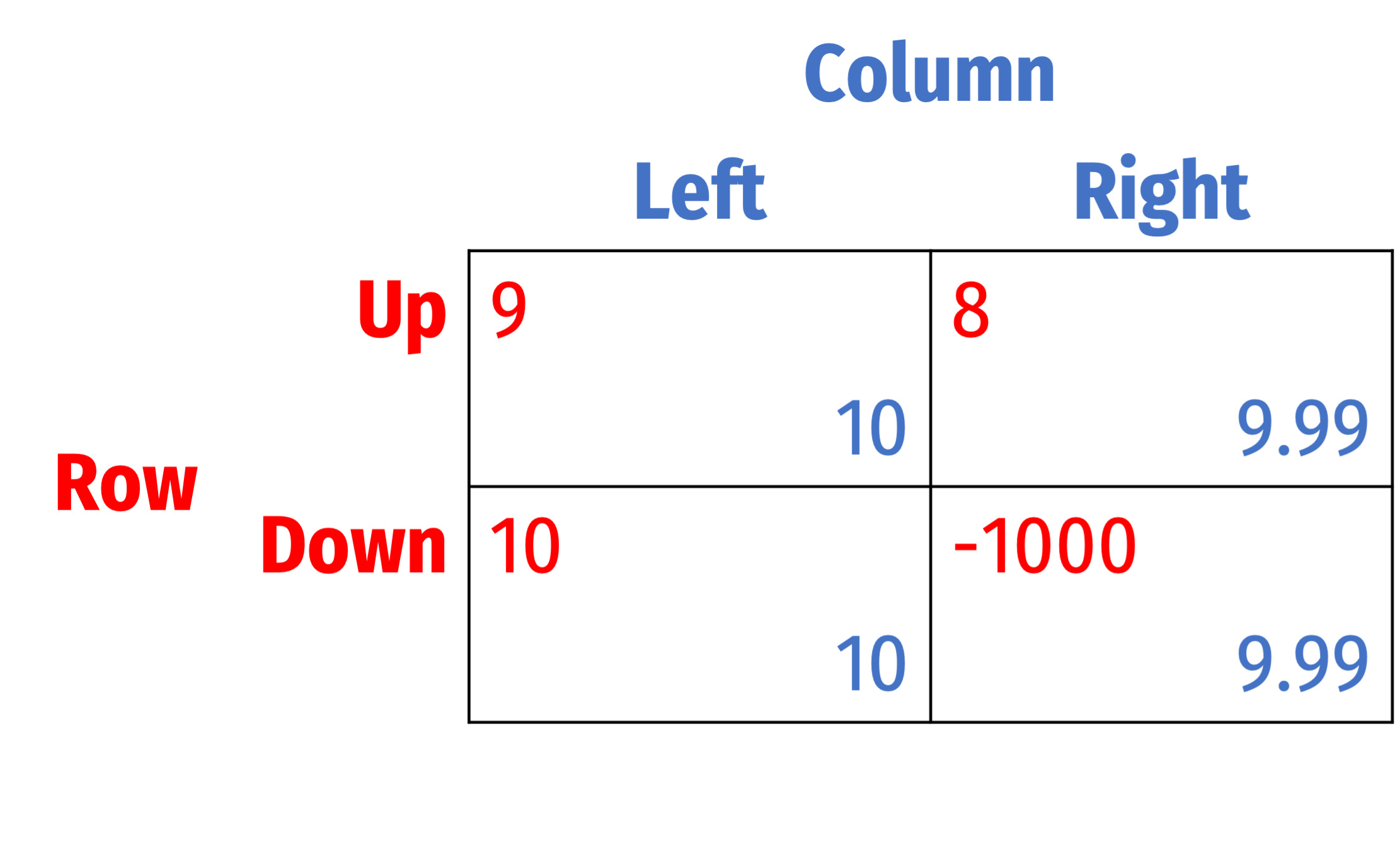

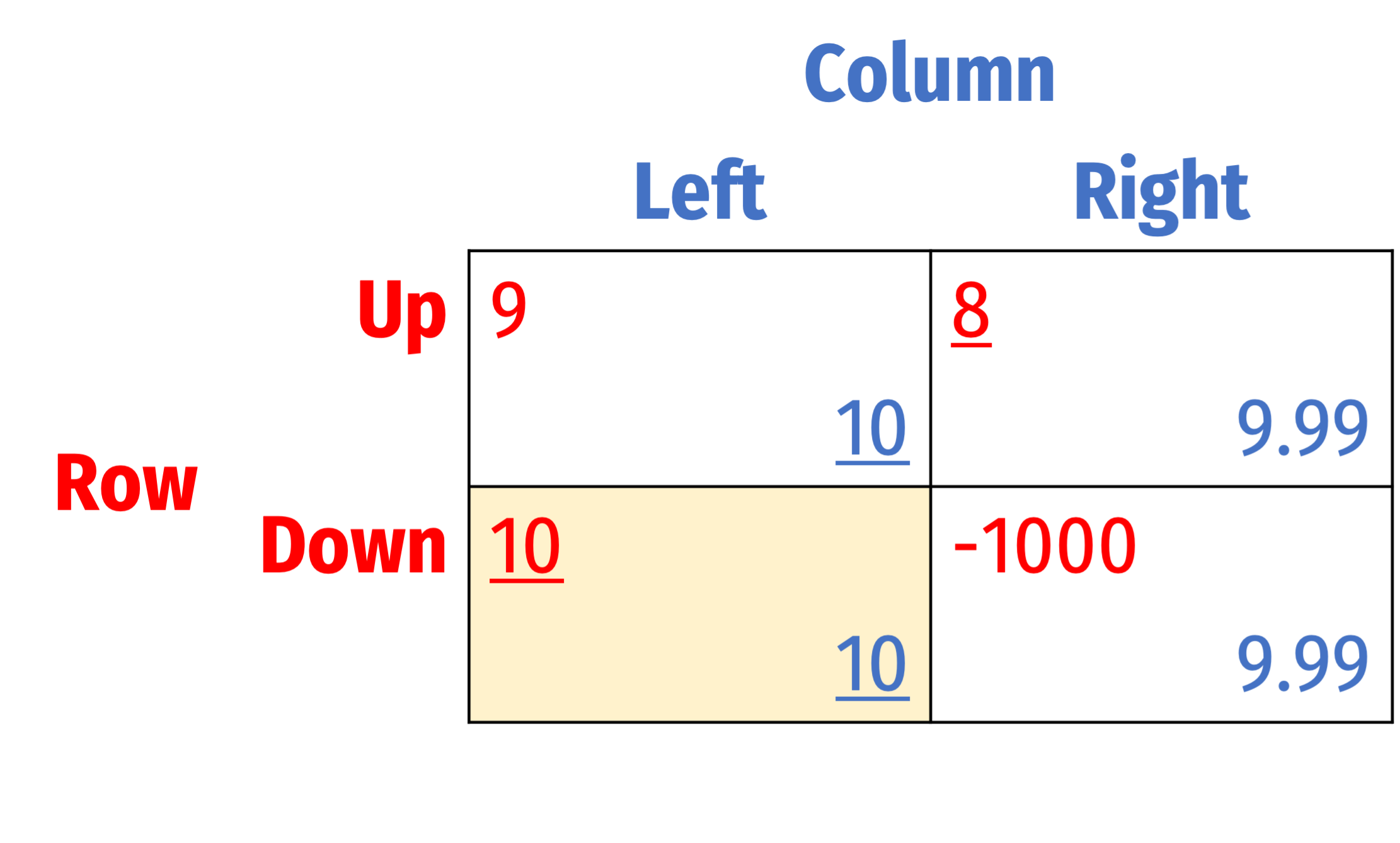

The Role of Beliefs

- Consider the following game

The Role of Beliefs

Consider the following game

Column has a dominant strategy to always play Left

Given this, Row should play Down

Unique Nash equilibrium: (Down, Left)

The Role of Beliefs

- If you were playing as Row, would you risk playing Down if you believed there was the slightest chance that Column would play Right?

Nash Equilibrium and Beliefs

- Nash equilibrium requires players to have accurate beliefs about each others' actions

- Each player should choose the strategy with the highest-payoff given their beliefs about the other player's (choice of) strategy

- These beliefs should be correct, i.e. match what the other players actually do

Nash Equilibrium and Beliefs

Rationalizable game outcomes are a more general solution concept than Nash equilibrium

- Allows for variations in beliefs

Nash equilibria are a subset of rationalizable outcomes

- Where players' maximize their payoff and their beliefs happen to be correct

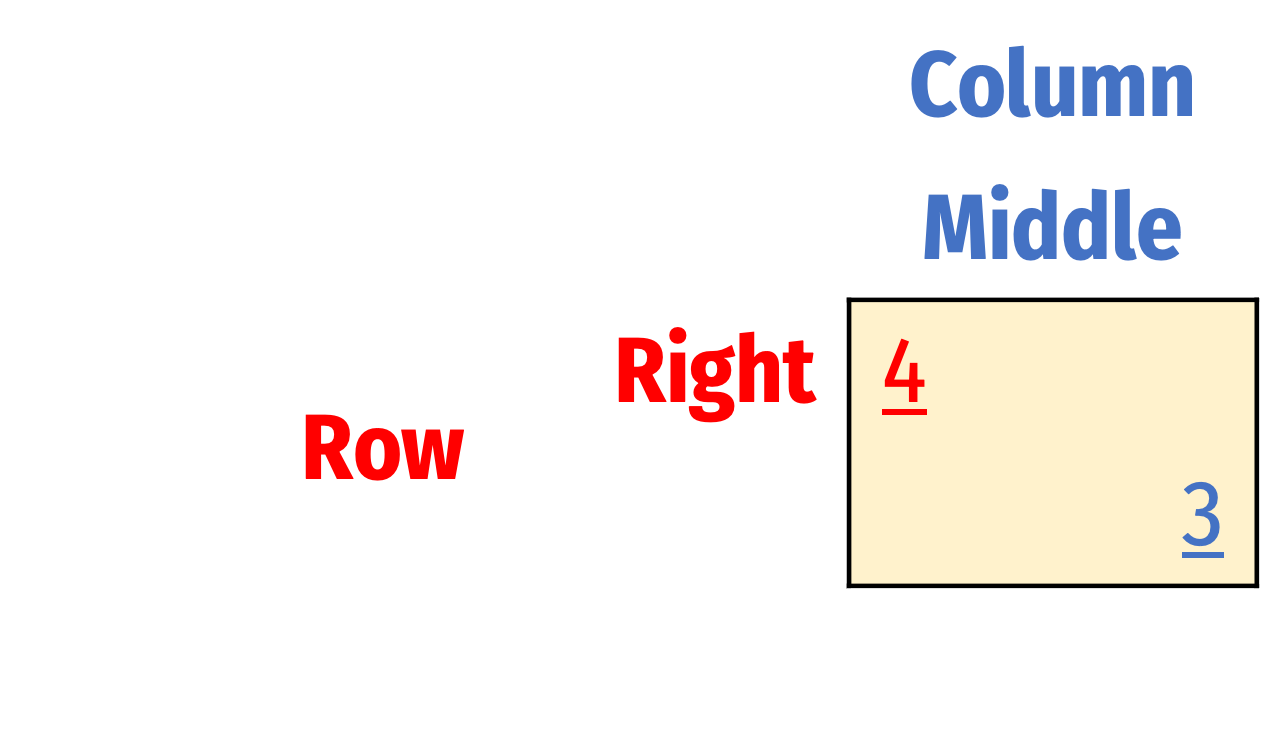

Rationalizability

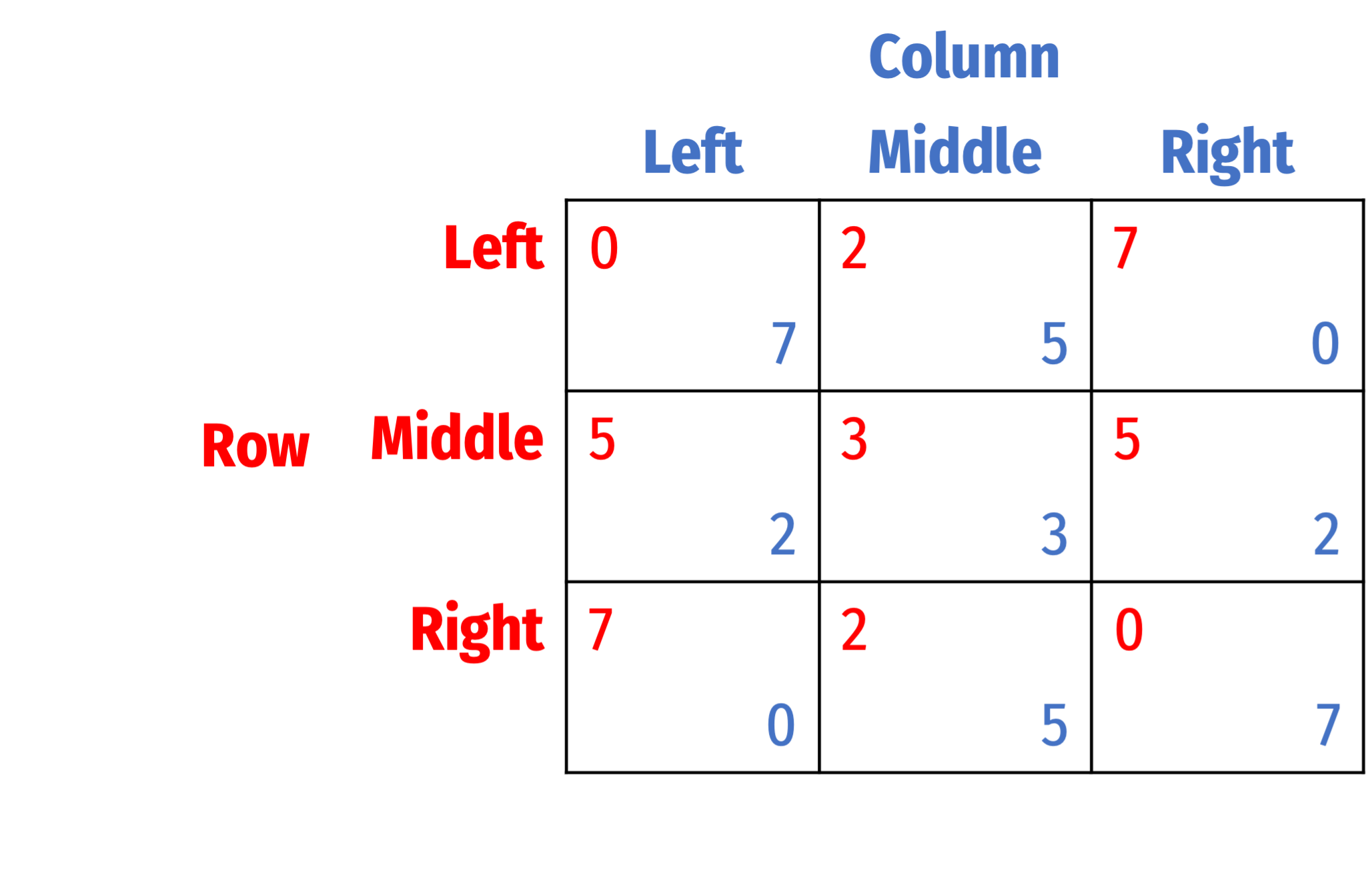

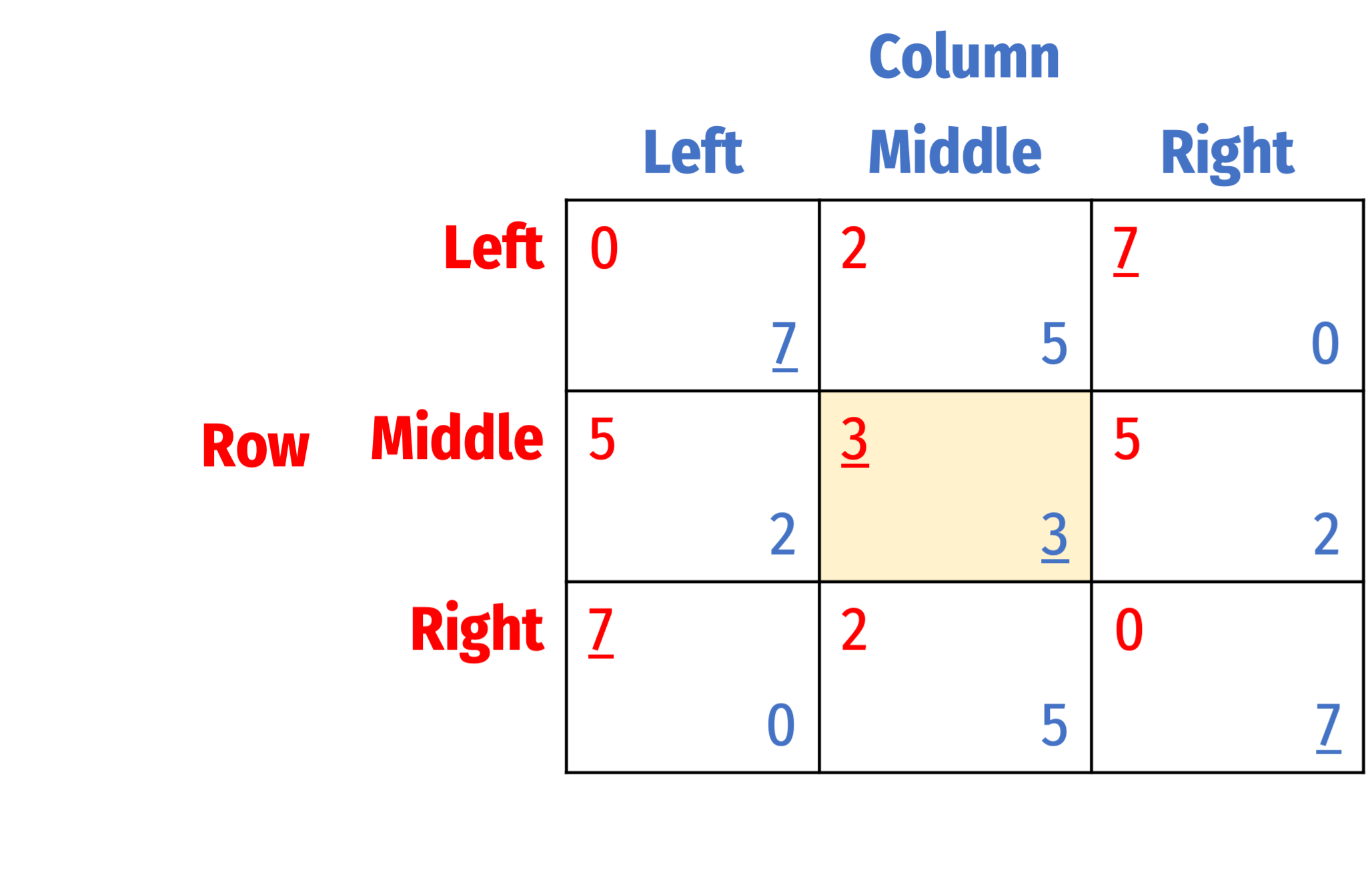

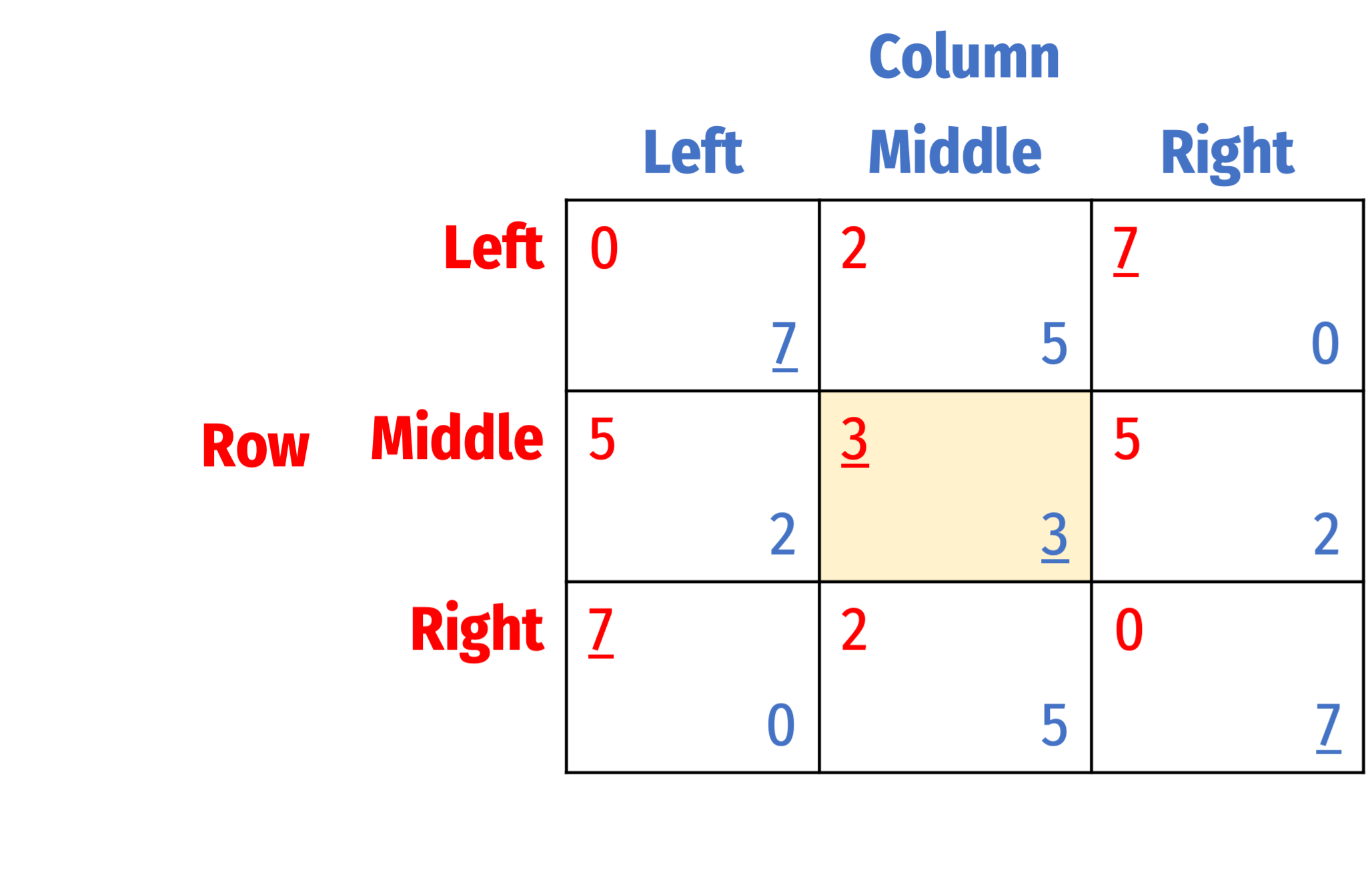

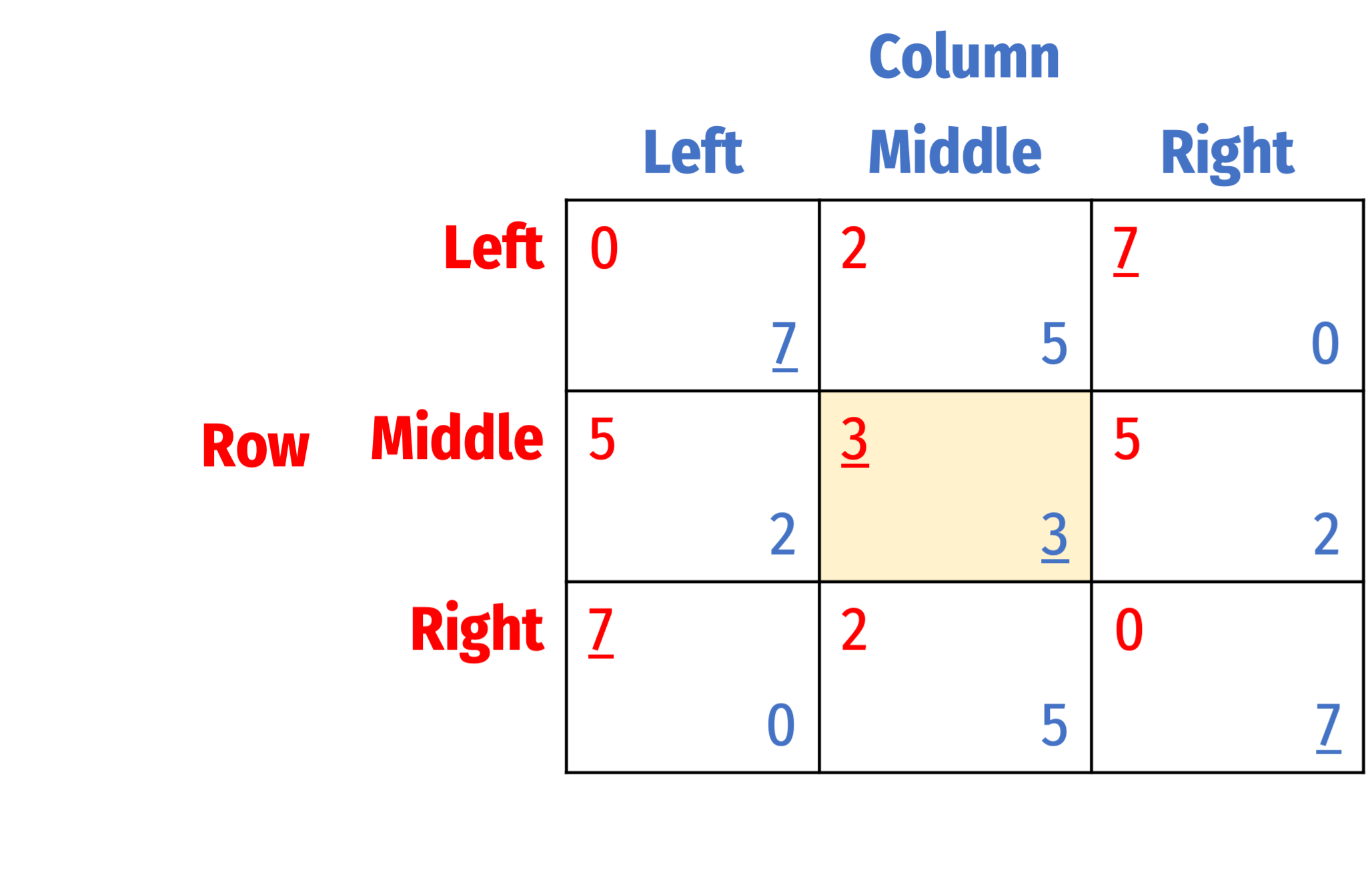

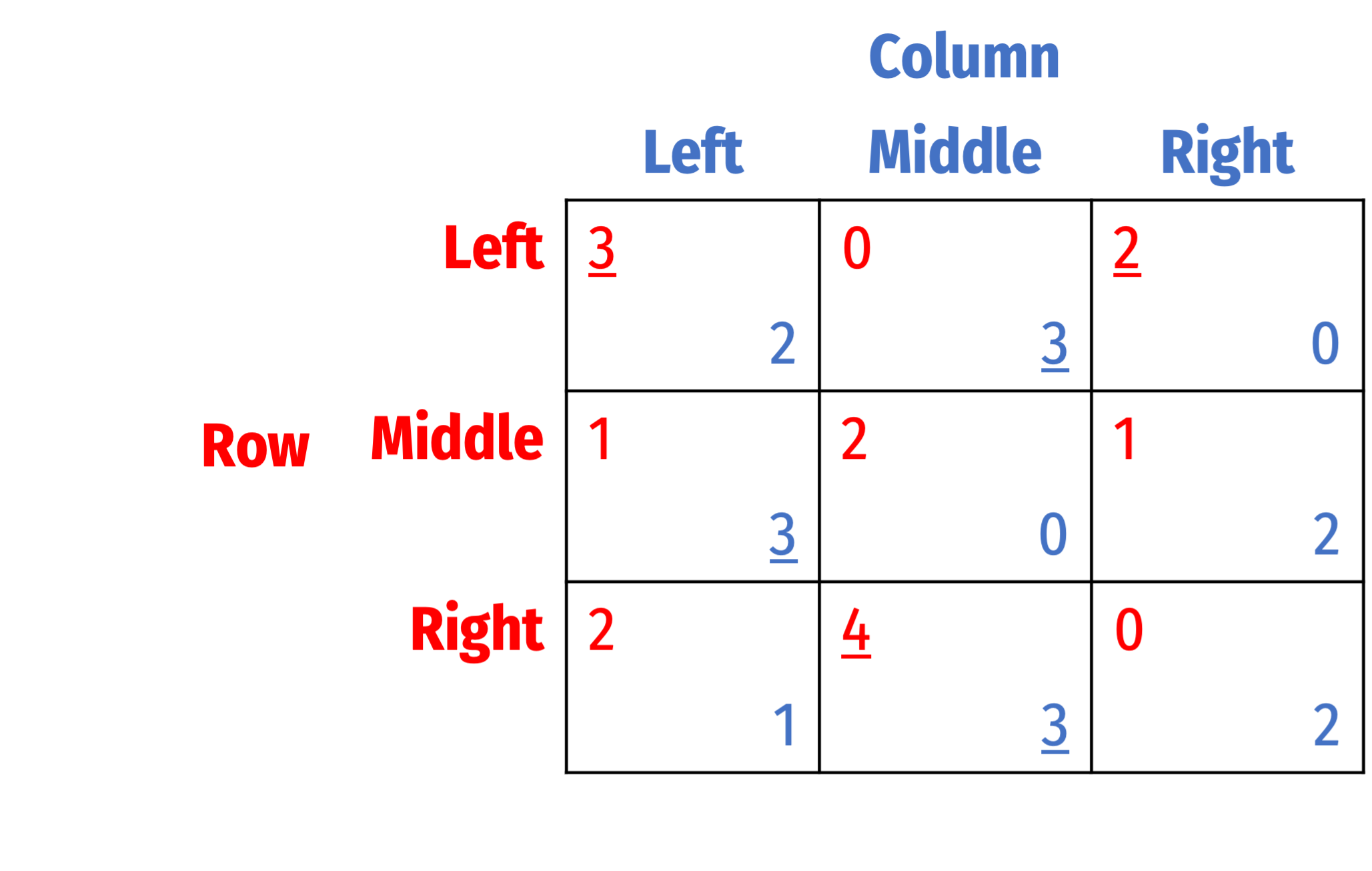

- Consider the following game

Rationalizability

Consider the following game

Solved using best response analysis, we see a unique Nash equilibrium: (Middle, Middle)

Rationalizability

Row plays Middle because she believes Column will rationally play Middle (who plays that because he believes that Row will play Middle)...

But players can also rationalize other possibilities

Rationalizability

For example, Row can rationalize playing Left

- If she thinks Column will play Right, then playing Left is her best response

Column can rationalize playing Right

- If he thinks Row will play Right, then playing Right is his best response

Similarly, we can rationalize many game outcomes under certain beliefs that players have

Rationalizability

- In this particular game (i.e. not every game!), all 9 outcomes are rationalizable!

(1) (Left, Left): Row will play Left if she believes Column will play Right; Column will play Left if he believes Row will play Left

(2) (Left, Middle): Row will play Left if she believes Column will play Right; Column will play Middle if he believes Row will play Middle

(3) (Left, Right): Row will play Left if she believes Column will play Right; Column will play Right if he believes Row will play Right

Rationalizability

- In this particular game (i.e. not every game!), all 9 outcomes are rationalizable!

(4) (Middle, Left): Row will play Middle if she believes Column will play Middle; Column will play Left if he believes Row will play Left

(5) (Middle, Middle): Row will play Middle if she believes Column will play Middle; Column will play Middle if he believes Row will play Middle

(6) (Middle, Right): Row will play Middle if she believes Column will play Middle; Column will play Right if he believes Row will play Right

Rationalizability

- In this particular game (i.e. not every game!), all 9 outcomes are rationalizable!

(7) (Right, Left): Row will play Right if she believes Column will play Left; Column will play Left if he believes Row will play Left

(8) (Right, Middle): Row will play Right if she believes Column will play Left; Column will play Middle if he believes Row will play Middle

(9) (Right, Right): Row will play Right if she believes Column will play Left; Column will play Right if he believes Row will play Right

Rationalizability and Best Reponses

What is key here is that players can rationalize playing a strategy if it is a best response to at least one strategy

Inversely, if a strategy is never a best response, playing it is not rationalizable

For this game, since each strategy is sometimes a best-response, for both players, all 9 outcomes are rationalizable

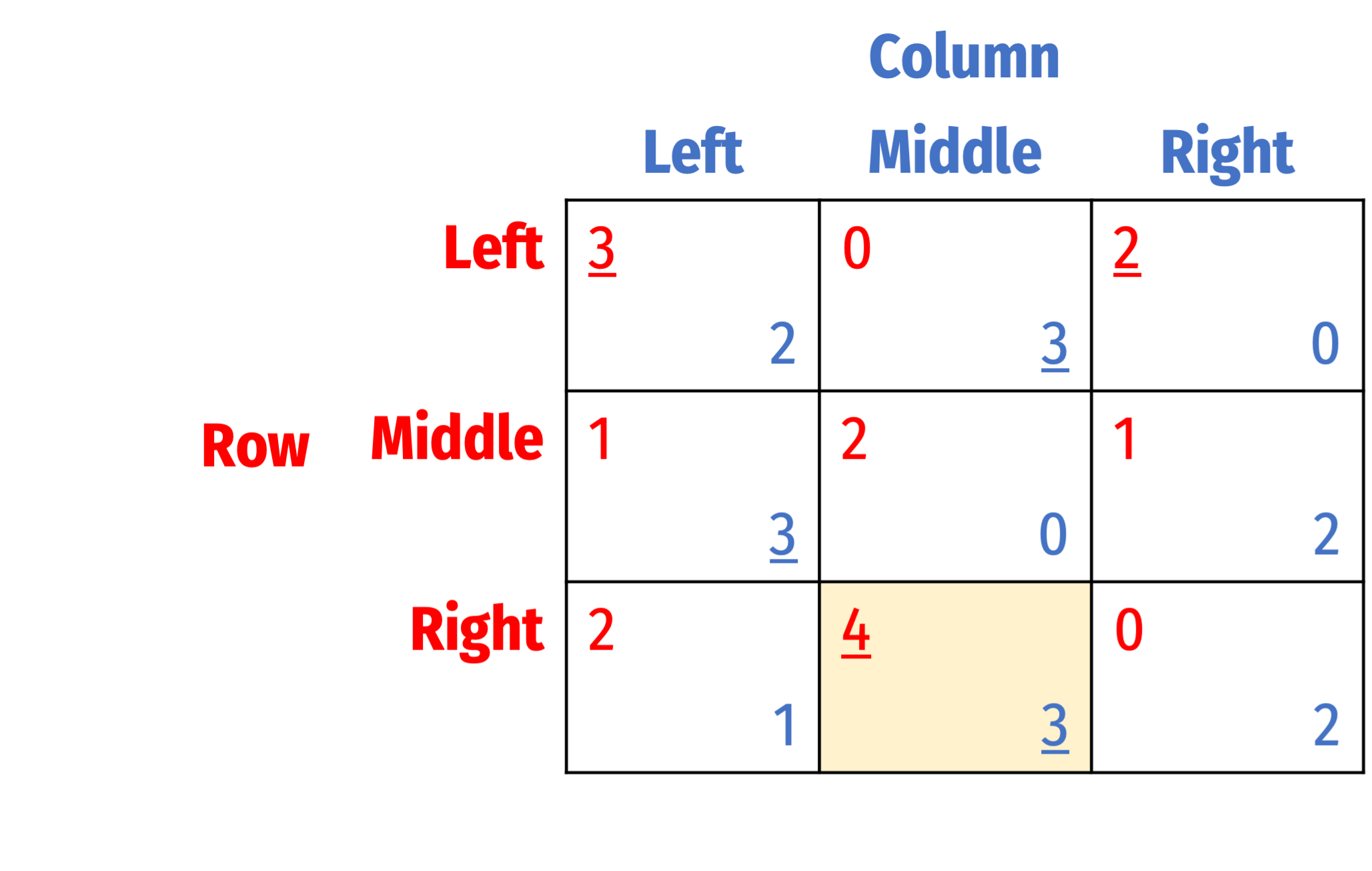

Rationalizability and Best Responses

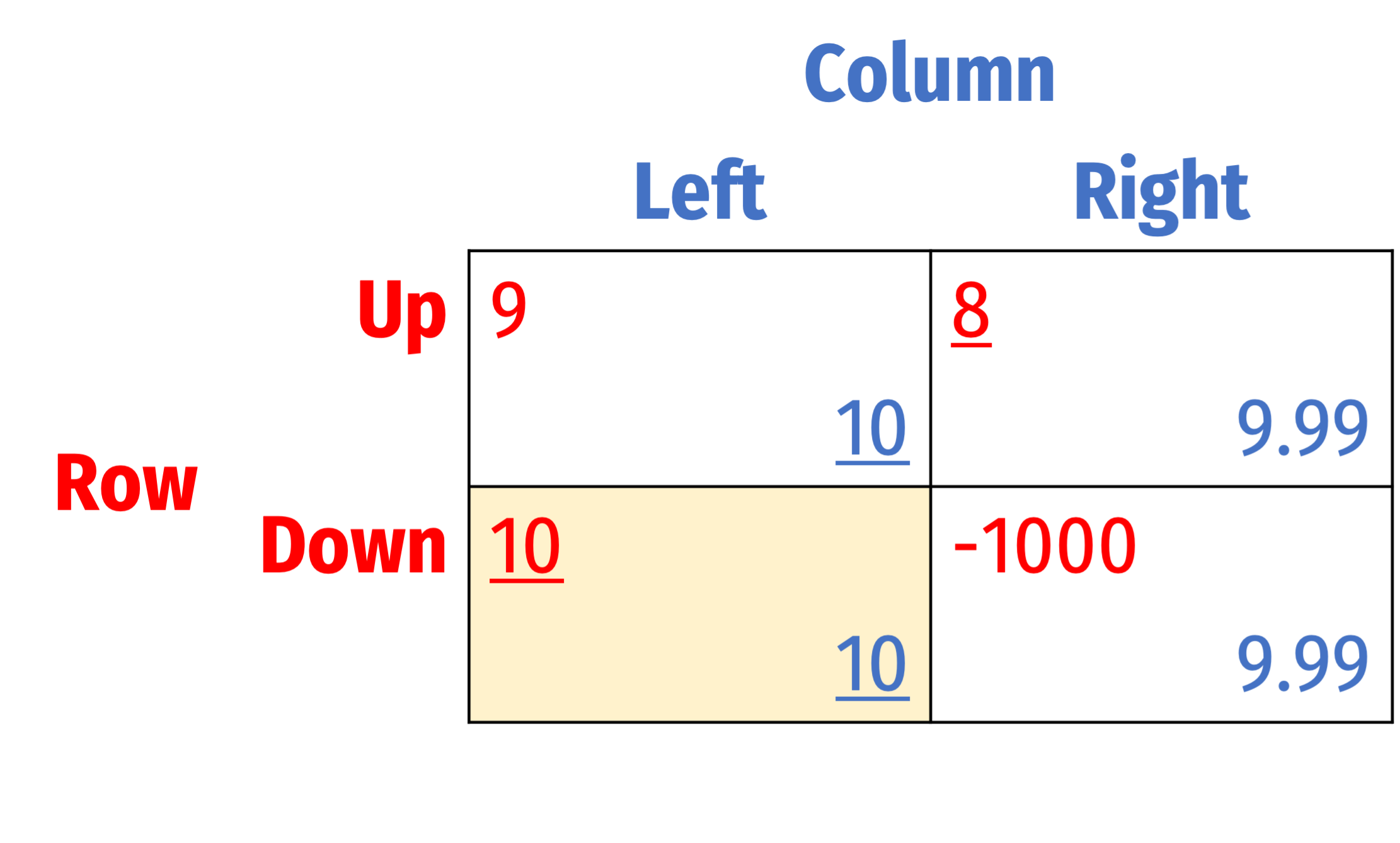

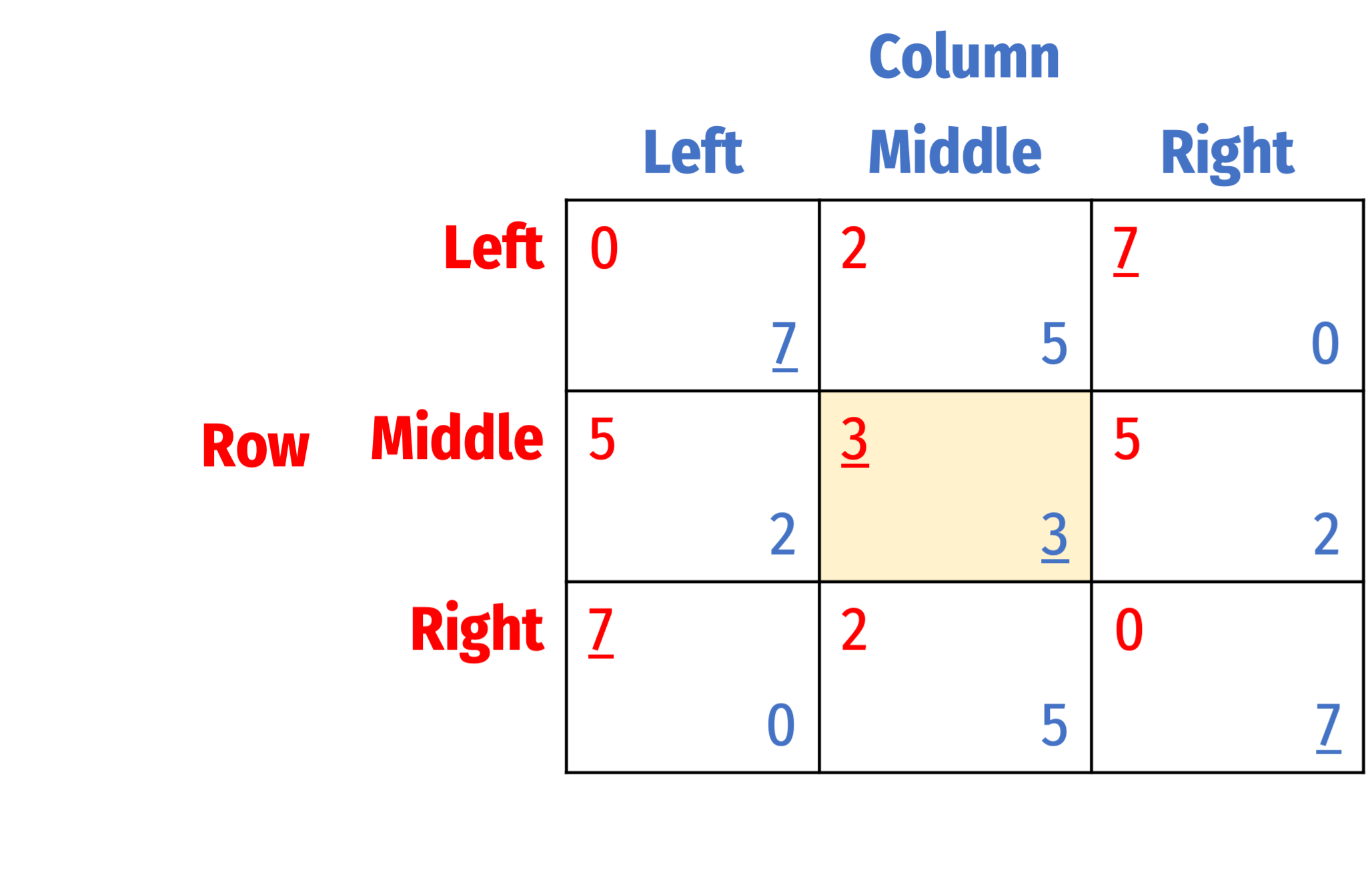

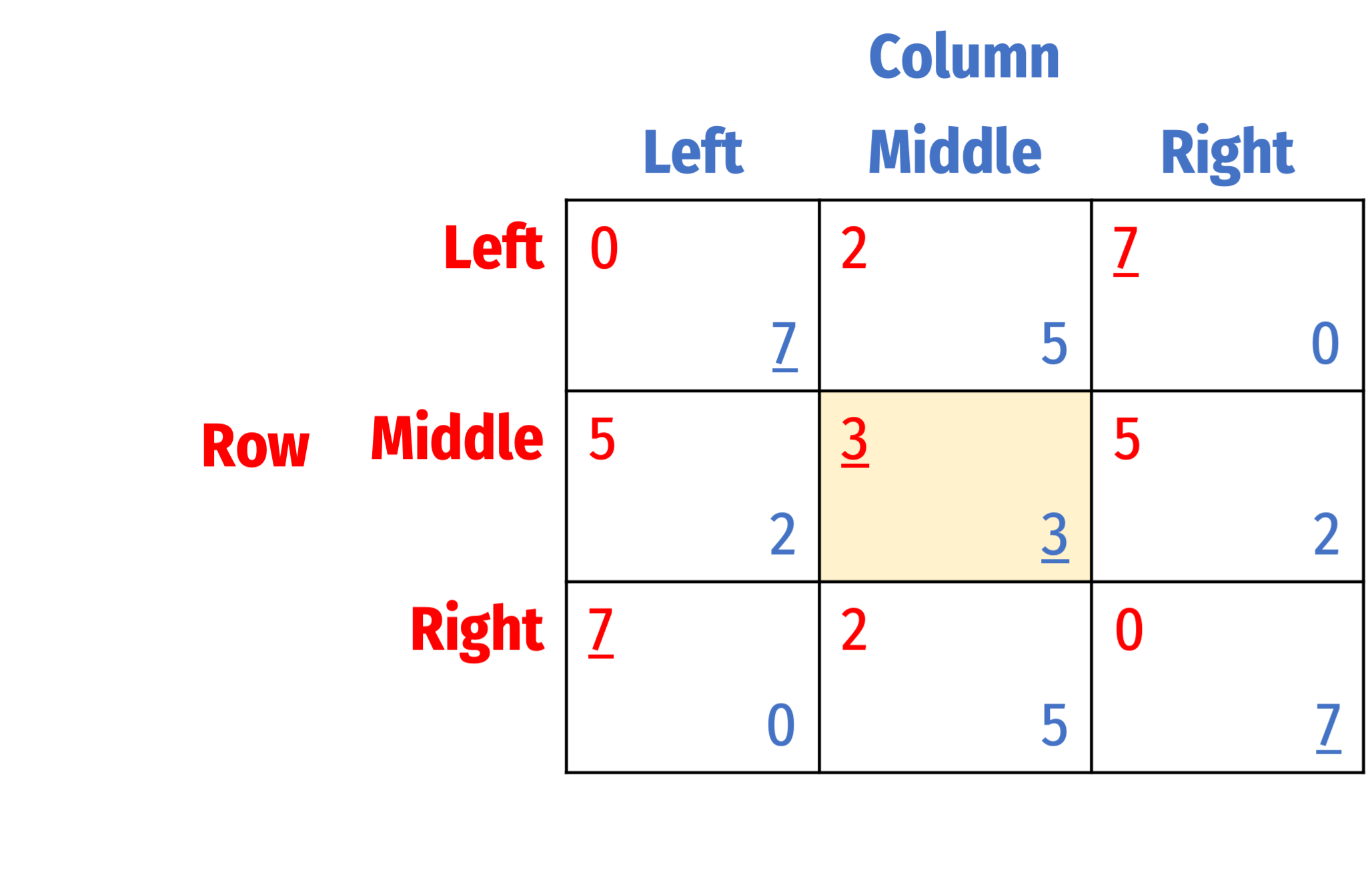

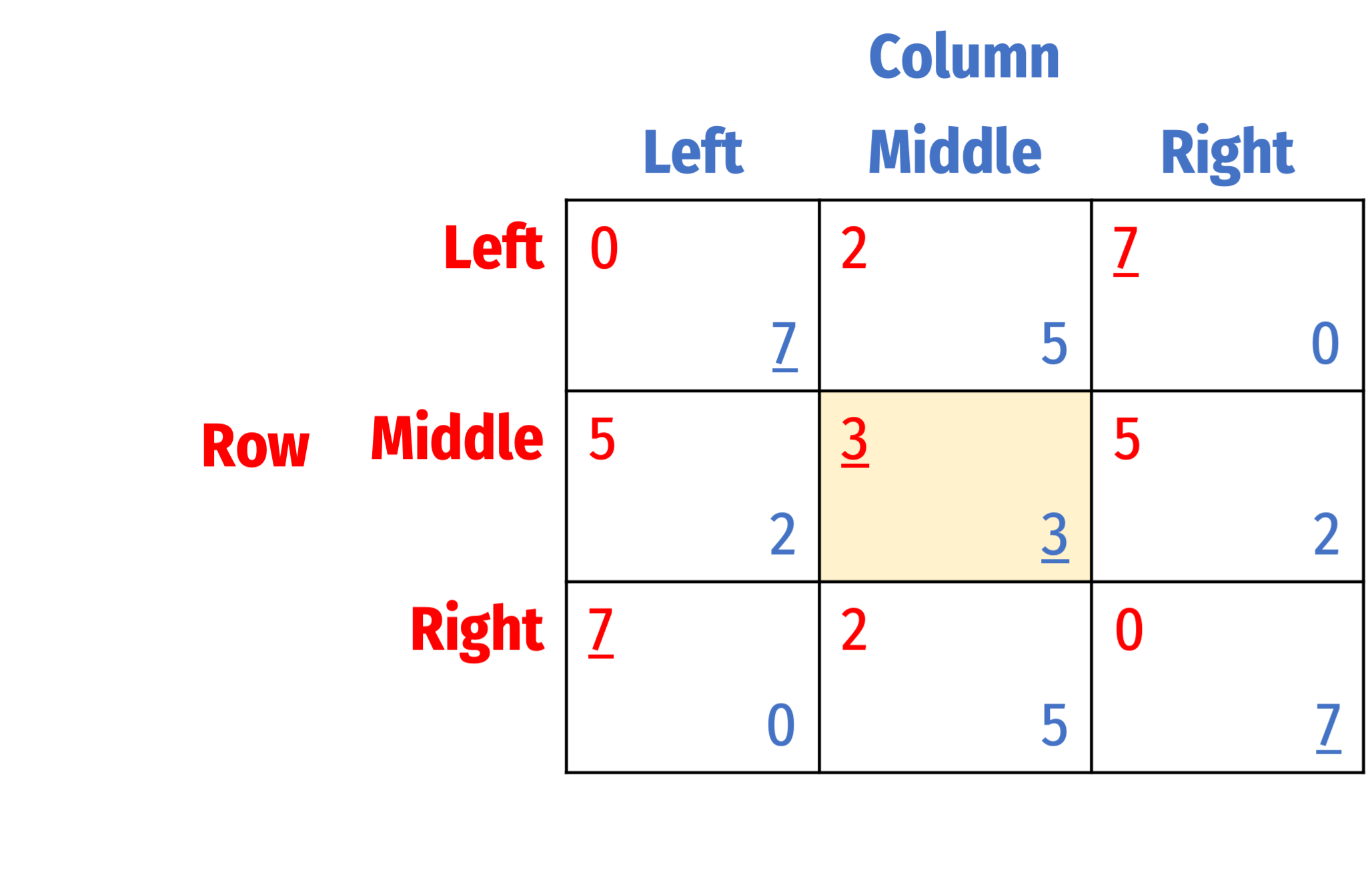

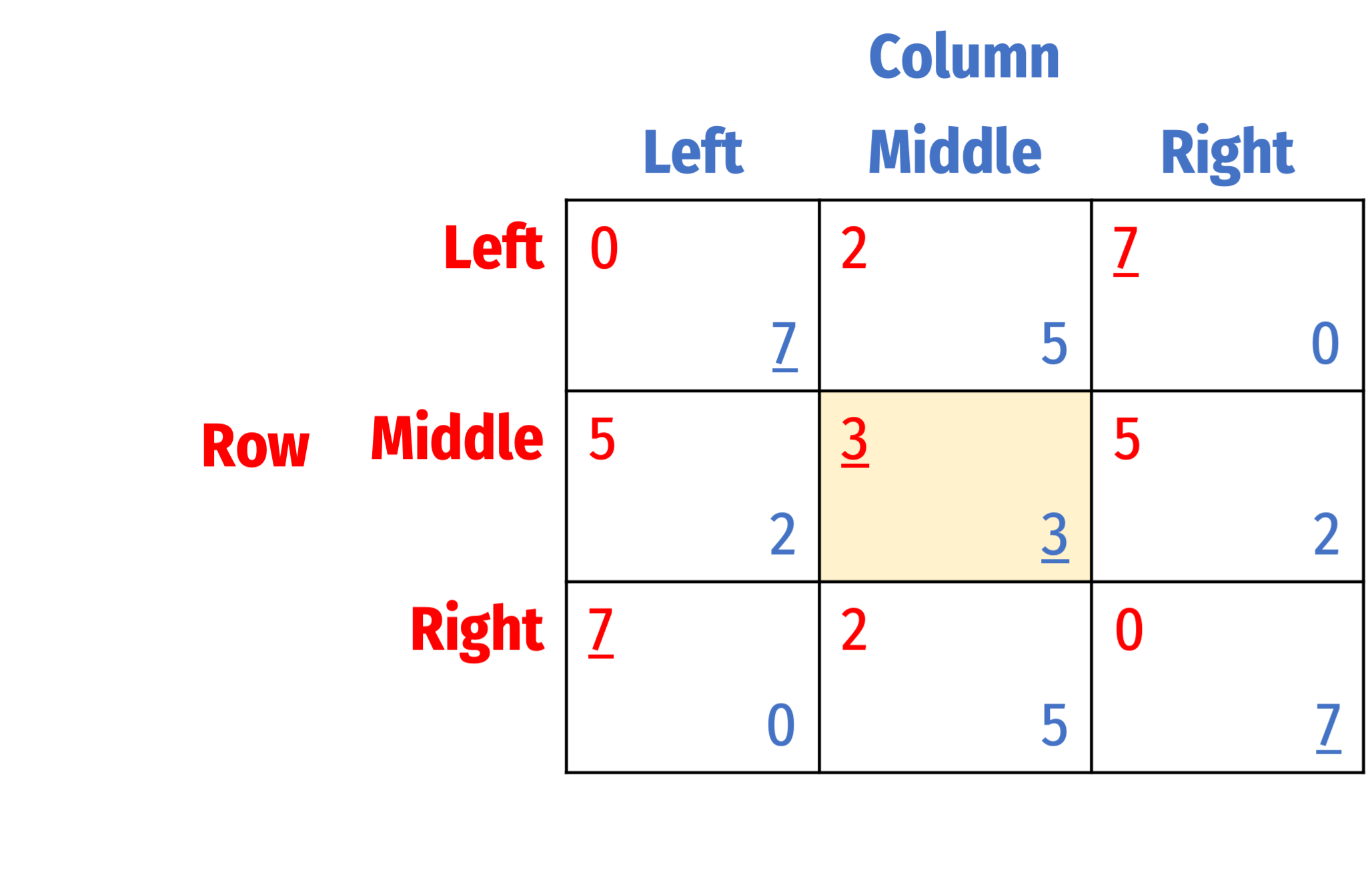

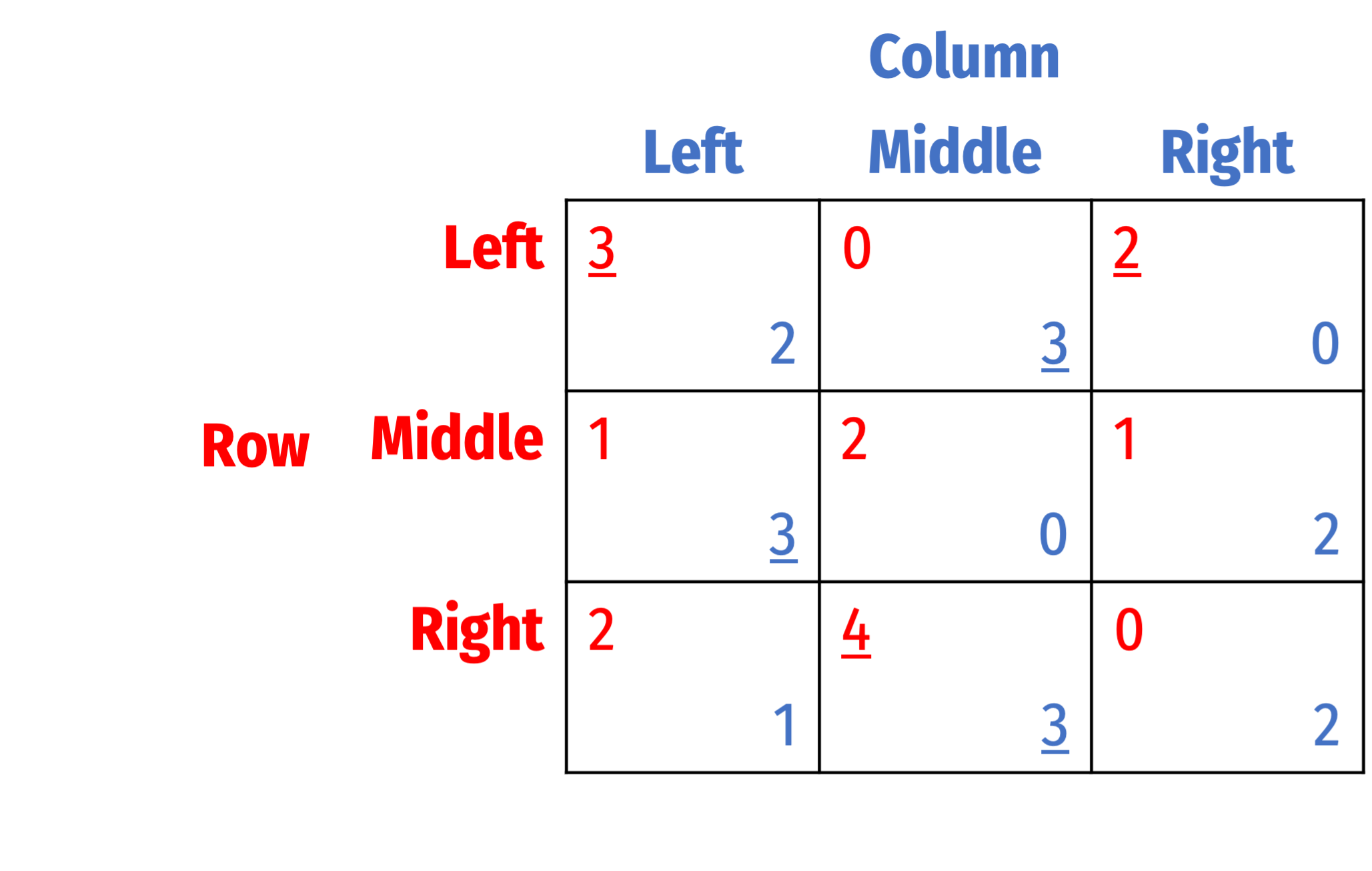

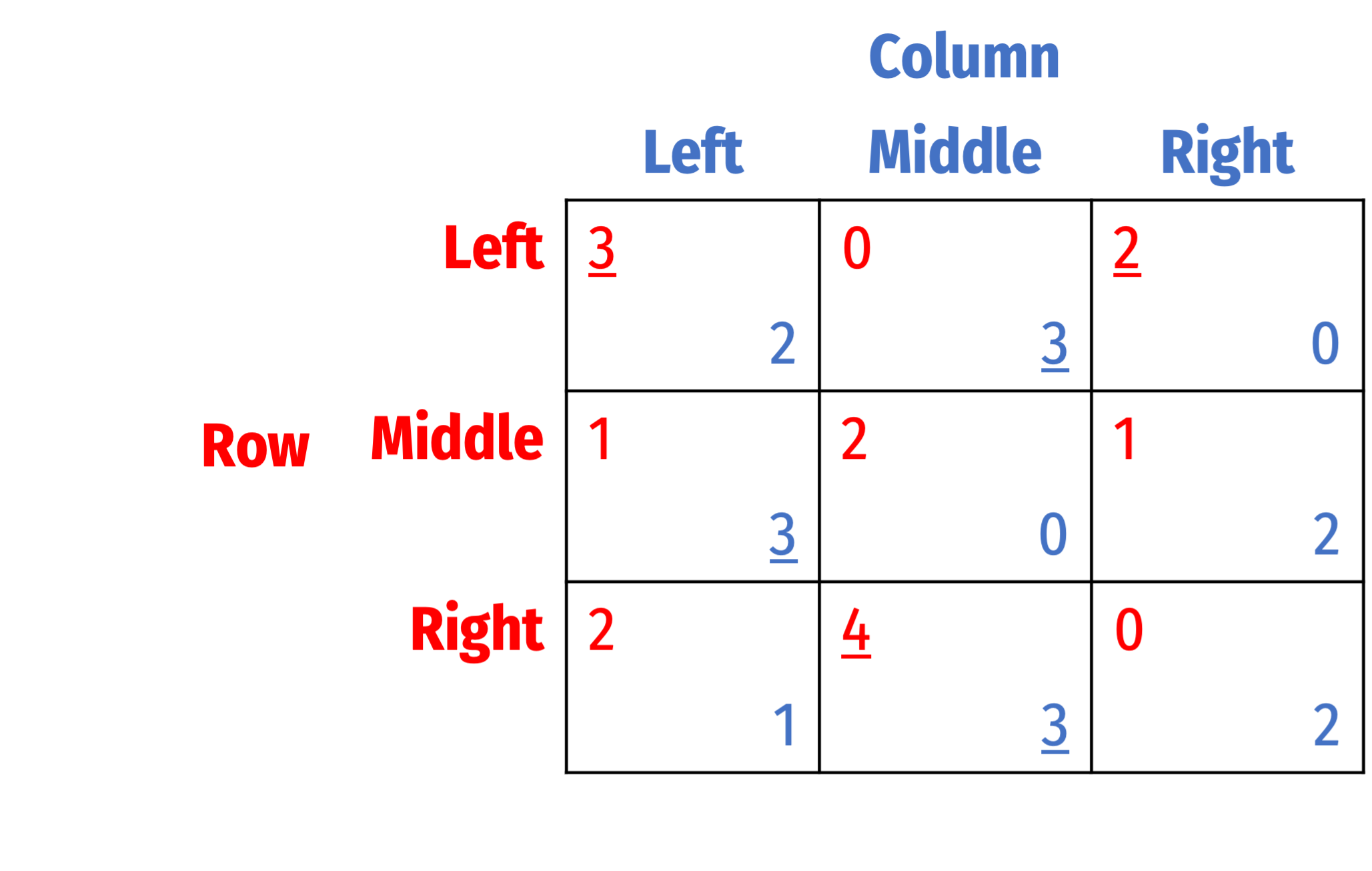

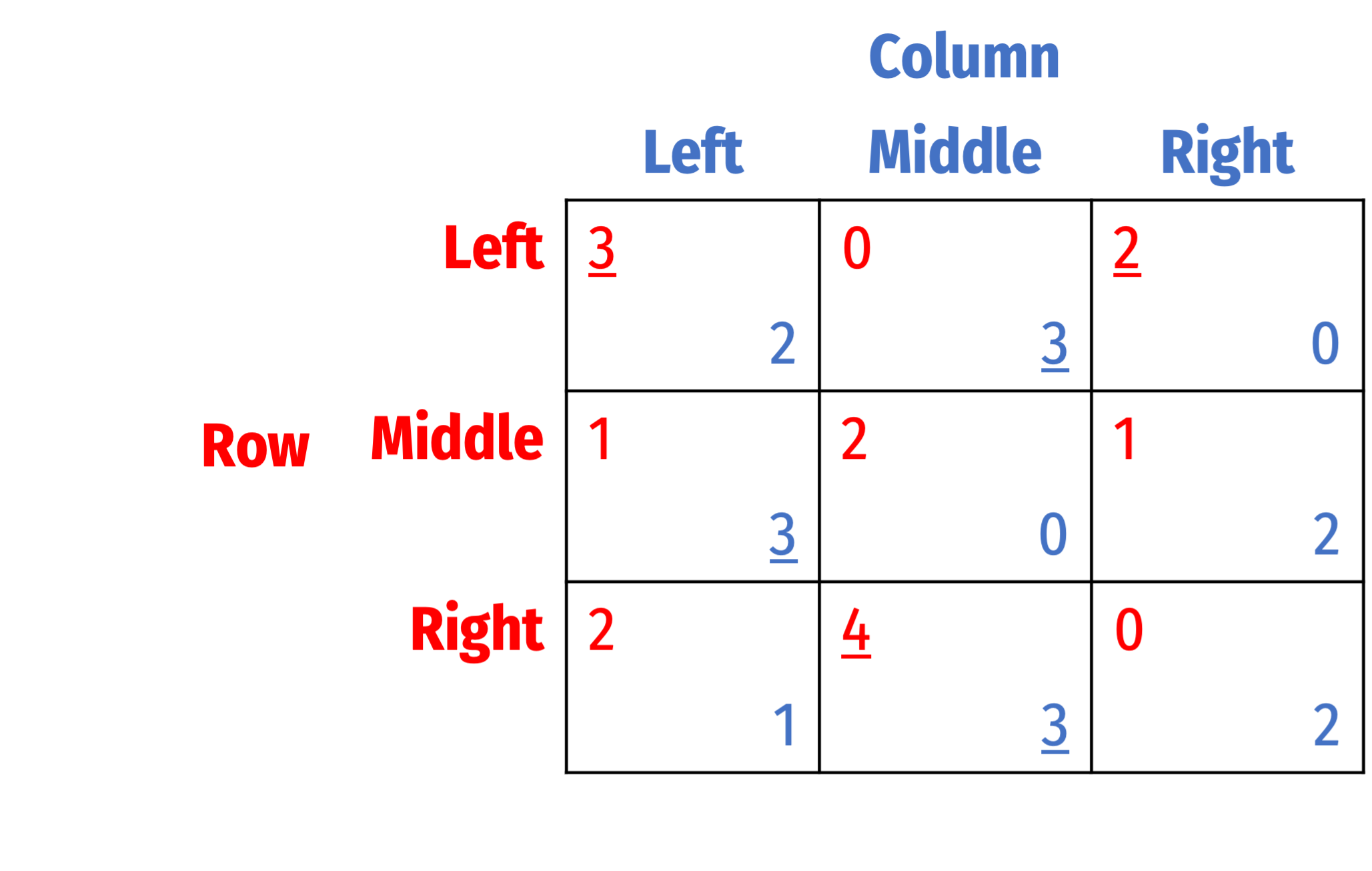

Rationalizability can sometimes find us the Nash equilibrium

Consider the game with some different payoffs

Rationalizability and Best Responses

Rationalizability can sometimes find us the Nash equilibrium

Consider the game with some different payoffs

First, find all best responses

Rationalizability and Best Responses

Rationalizability can sometimes find us the Nash equilibrium

Consider the game with some different payoffs

First, find all best responses, and next delete all strategies that are never a best response

Rationalizability and Best Responses

Rationalizability can sometimes find us the Nash equilibrium

Consider the game with some different payoffs

First, find all best responses, and next delete all strategies that are never a best response

- Note here there are no strictly dominated strategies!

Rationalizability and Best Responses

Rationalizability can sometimes find us the Nash equilibrium

Consider the game with some different payoffs

First, find all best responses, and next delete all strategies that are never a best response

- Note here there are no strictly dominated strategies!

- For Row, playing Middle is never a best response

- For Column, playing Right is never a best response

Rationalizability and Best Responses

- Now we see Column will not play Left

Rationalizability and Best Responses

- Now we see Row will not play Left

Rationalizability and Best Responses

- This brings us to the outcome that is the Nash equilibrium: (Right, Middle)

Rationalizability and Best Responses

- This brings us to the outcome that is the Nash equilibrium: (Right, Middle)

Rationalizability and Best Responses

- We will examine the role of beliefs much more rigorously later in the semester when we consider games with incomplete information and Bayesian games (and a whole separate set of solution concepts!)