3.4 — Evolutionarily Stable Strategies

ECON 316 • Game Theory • Fall 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/gameF21

gameF21.classes.ryansafner.com

Evolution, Natural Selection, and Game Theory

Evolution by Natural Selection

- Evolution: change over time in one or more inherited traits in populations of individuals

“[I]f variations useful to any organic being do occur, assuredly individuals thus characterised will have the best chance of being preserved in the struggle for life; and from the strong principle of inheritance they will tend to produce offspring similarly characterised. This principle of preservation, I have called, for the sake of brevity, Natural Selection,” (Ch. 4).

Darwin, Charles, 1859, On the Origin of Species

Evolution by Natural Selection

Natural selection: Darwin’s greatest idea, main mechanism behind biological change, requires:

- Variation in organisms

- Differential reproduction (“fitness”)

- Heredity (replication)

Fitness: how good a replicator is at replicating relative to other types

“Fitter” traits becomes more common in a population of replicators over time

The Selfish Gene

At first glance, “players” in this game appear to be individual organisms

- But individuals only live through one life cycle of replication

In the long run, its really the strategies themselves (phenotypes — behavioral/traits of an organism) that are in competition over many many generations

These are expressed in the genotypes of organisms

Assume genes are selfish and are the “agent” to model:

- Objective is to maximize reproductive success

The Selfish Gene

Choose: < phenotype (“strategy”) >

In order to maximize: < reproductive fitness >

Subject to: < environment (including other organisms!) >

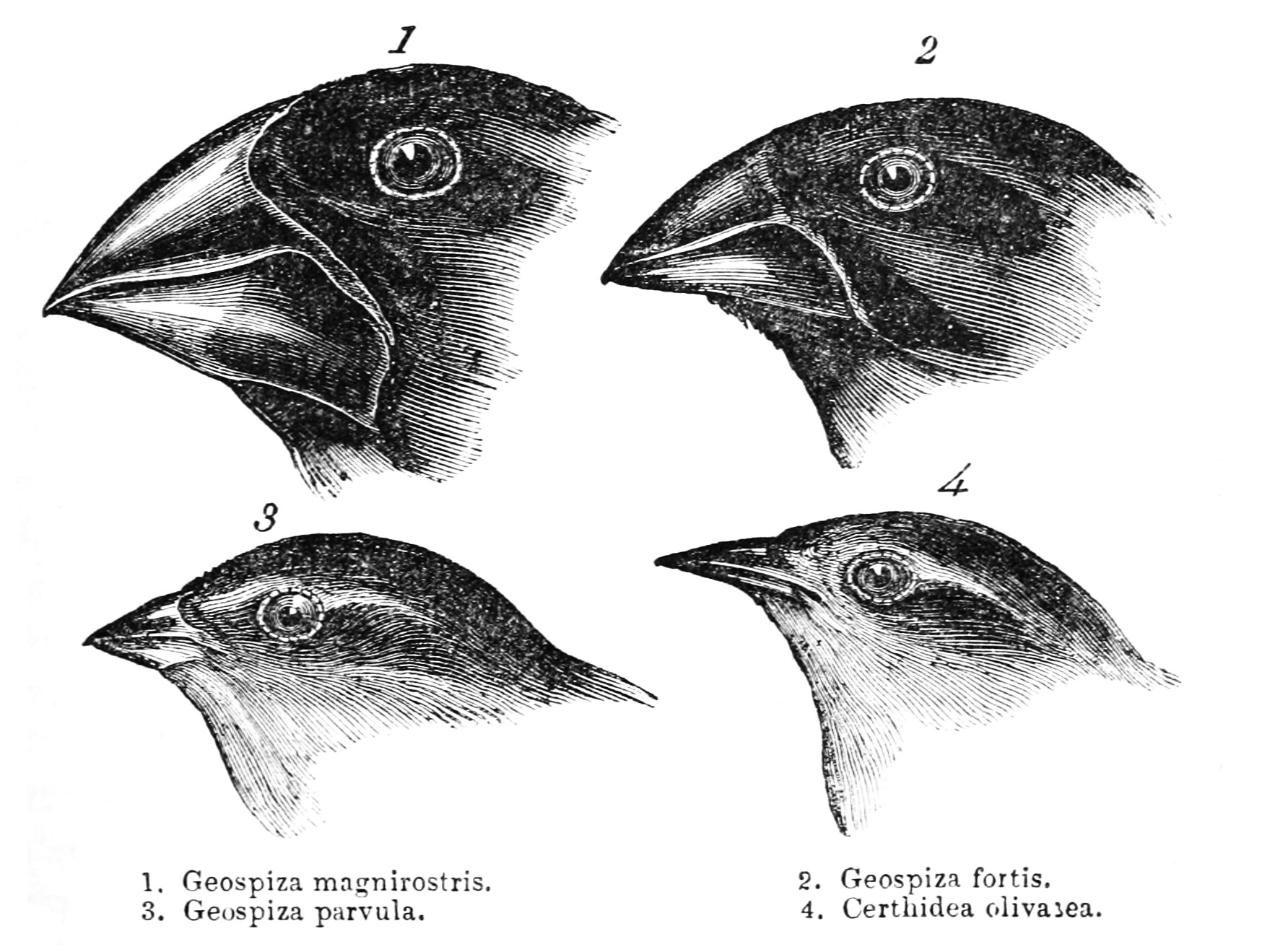

Natural Selection: Darwin’s Finches

Finches on the Galapagos Islands

Island experiences draughts

Finch population evolved deeper, stronger beaks that let them eat tougher seeds

Natural Selection: Darwin’s Finches

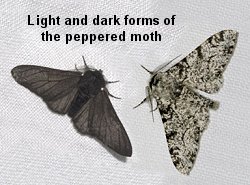

Both light and dark moths existed

Soot from the industrial revolution and coal-fired power plants turned many trees black

Being dark became an advantageous trait to hide from predators

After 50 years, nearly all moths become black

The Need for Evolutionary Game Theory

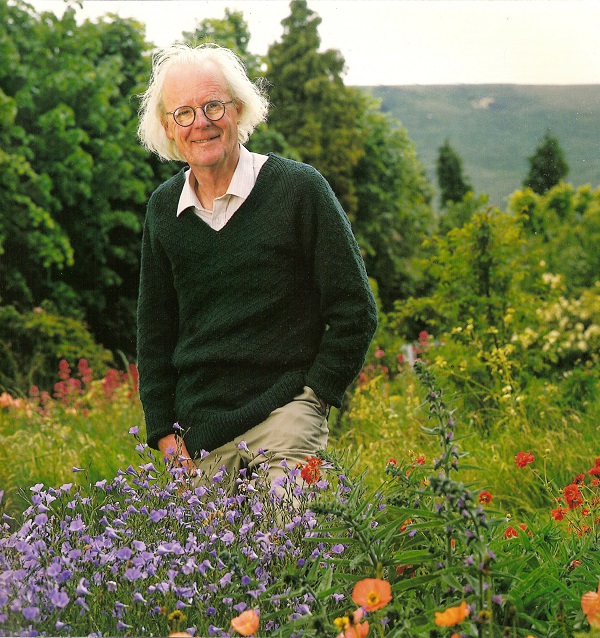

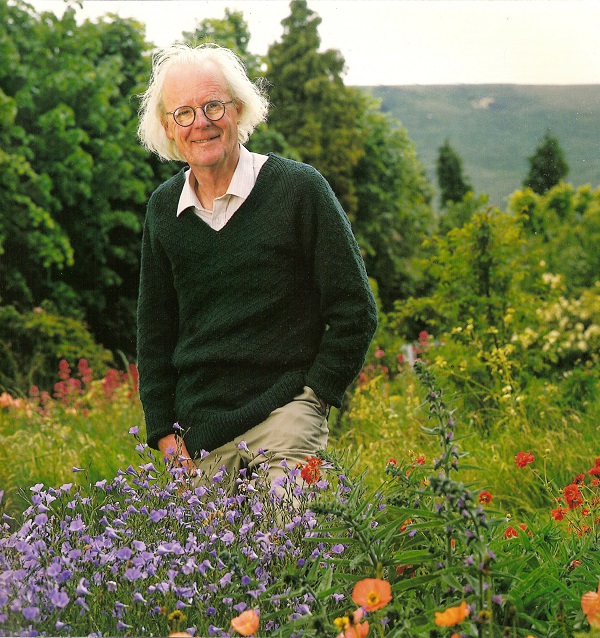

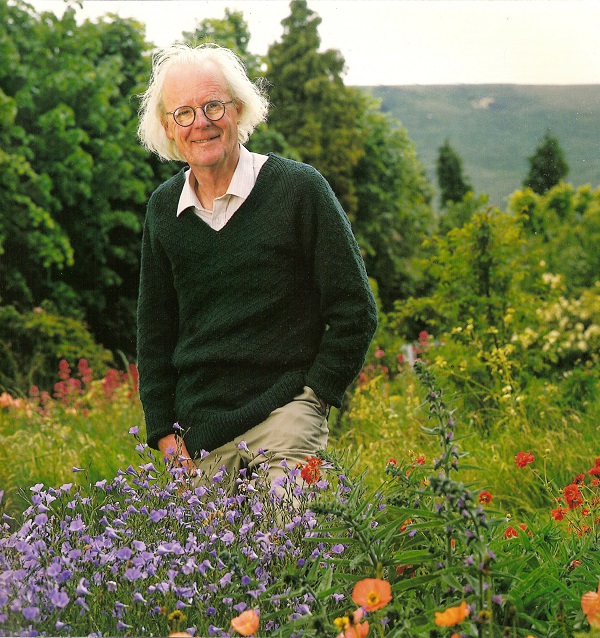

John Maynard Smith

1920—2004

“[If] we want to understand why selection has favoured particular phenotypes [then] the appropriate mathematical tool is optimisation theory. We are faced with the problem of deciding what particular features ... contribute to fitness, but not with the special difficulties which arise when success depends on what others are doing. It is in the latter context that game theory becomes relevant,” (p.1).

Maynard Smith, John, 1982, Evolution and the Theory of Games

The Need for Evolutionary Game Theory II

John Maynard Smith

1920—2004

“Sensibly enough, a central assumption of classical game theory is that the players will behave rationally, and according to some criterion of self-interest. Such an assumption would clearly be out of place in an evolutionary context. Instead, the criterion of rationality is replaced by that of population dynamics and stability, and the criterion of self-interest by Darwinian fitness,” (p.2).

Maynard Smith, John, 1982, Evolution and the Theory of Games

Evolutionary Game Theory

Fitness of an individual depends on what others do — strategic interaction

- These are often “hard wired”, not conscious strategies

This creates an evolutionary biological game

- Players: members of a population/species

- Strategies: “phenotype”: traits, behavior, appearance, etc

- Payoffs: fitness

Evolutionary Game Theory II

John Maynard Smith

1920—2004

“A ‘strategy’ is a behavioural phenotype; i.e. it is a specification ofwhat an individual will do in any situation in which it may find itself,” (p.10).

“The idea, however, can be applied equally well to any kind of phenotypic variation, and the word strategy could be replaced by the word phenotype; for example, a strategy could be the growth form of a plant, or the age at first reproduction, or the relative numbers of sons and daughters produced by a parent,” (p.10).

Maynard Smith, John, 1982, Evolution and the Theory of Games

Evolutionary Game Theory III

Fitter phenotypes enjoy reproductive success and continue into future generations

From time to time, random mutations occur that create new phenotypes

If this phenotype is more fit than the original, it may successfully invade a population and replace it

Biologists call a population configuration of phenotypes that cannot be successfully invaded an evolutionarily stable strategy (ESS)

Evolutionary Game Theory IV

John Maynard Smith

1920—2004

“An ESS is a strategy such that, if all the members of a population adopt it, then no mutant strategy could invade the population under the influence of natural selection,” (p.10).

Maynard Smith, John, 1982, Evolution and the Theory of Games

Evolutionary Game Theory V

- Two types of ESS population configurations:

- Monomorphic: every individual plays the same strategy (is same phenotype)

- Polymorphic: different individuals playing different strategies (multiple phenotypes)

- Akin to populations playing mixed strategies

- Different groups of a population where all individuals in that group play same pure strategy

Model and Purpose

Main focus is on population dynamics and changes of strategy

Want to find stable ESS where populations don't change strategies

Start with large population of organisms (of same species) with same phenotype (strategy)

Within-species evolution:

- Strategies and payoffs are the same

- Symmetric games

Model and Purpose II

Heredity:

- With high probability (1−ϵ), each individual adopts parent's strategy

- With low probability (ϵ), individual plays another strategy (mutation)

Individuals within population are randomly matched to (to play game)

Payoffs represent (reproductive) fitness

Model and Purpose II

Strategies with higher fitness spread, those with lower fitness diminish

Over time, mutations of higher fitness spread and replace those of lower fitness

ESS where a population playing a strategy can not be successfully invaded and replaced by another strategy

Evolutionarily Stable Strategies

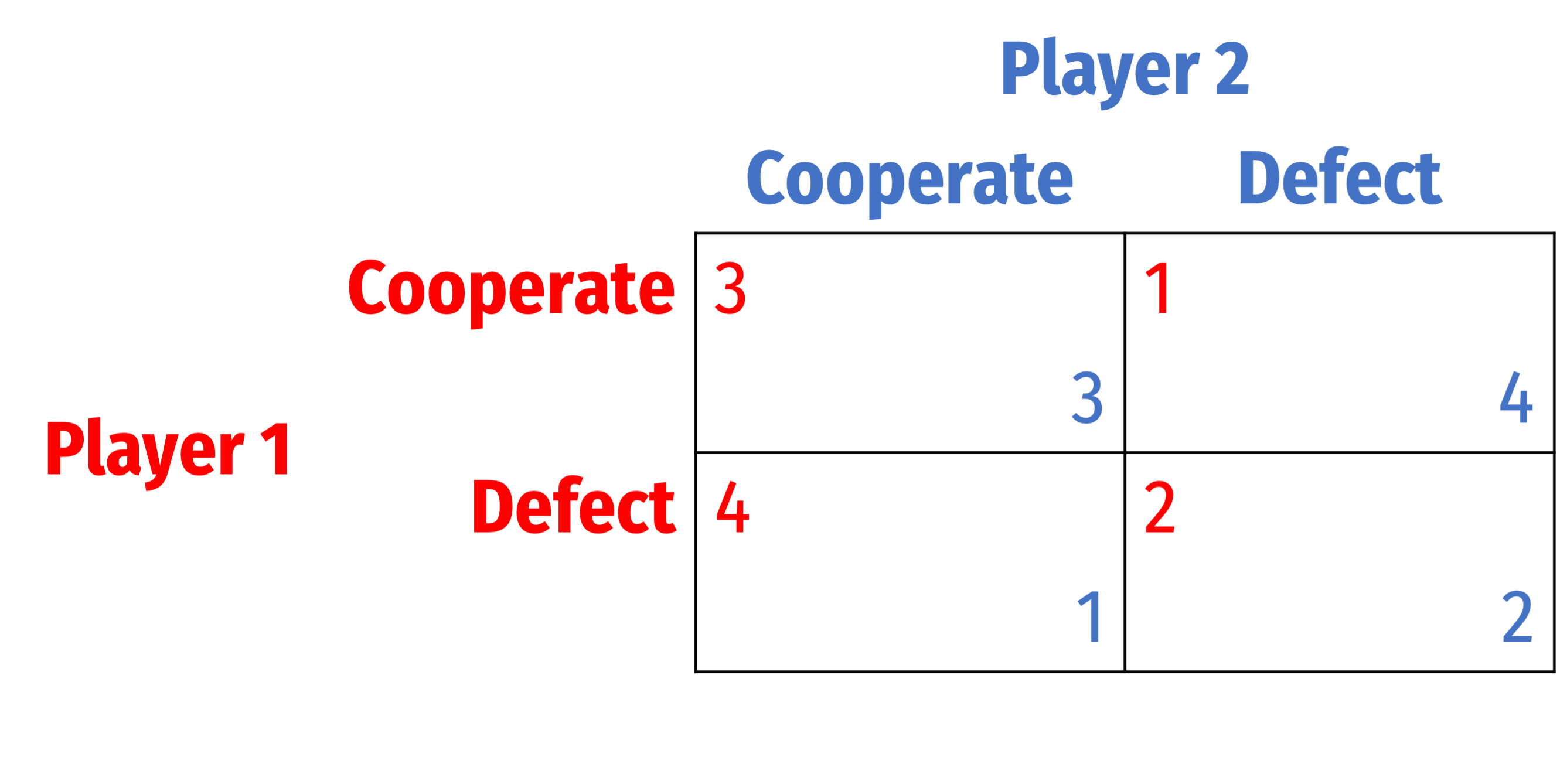

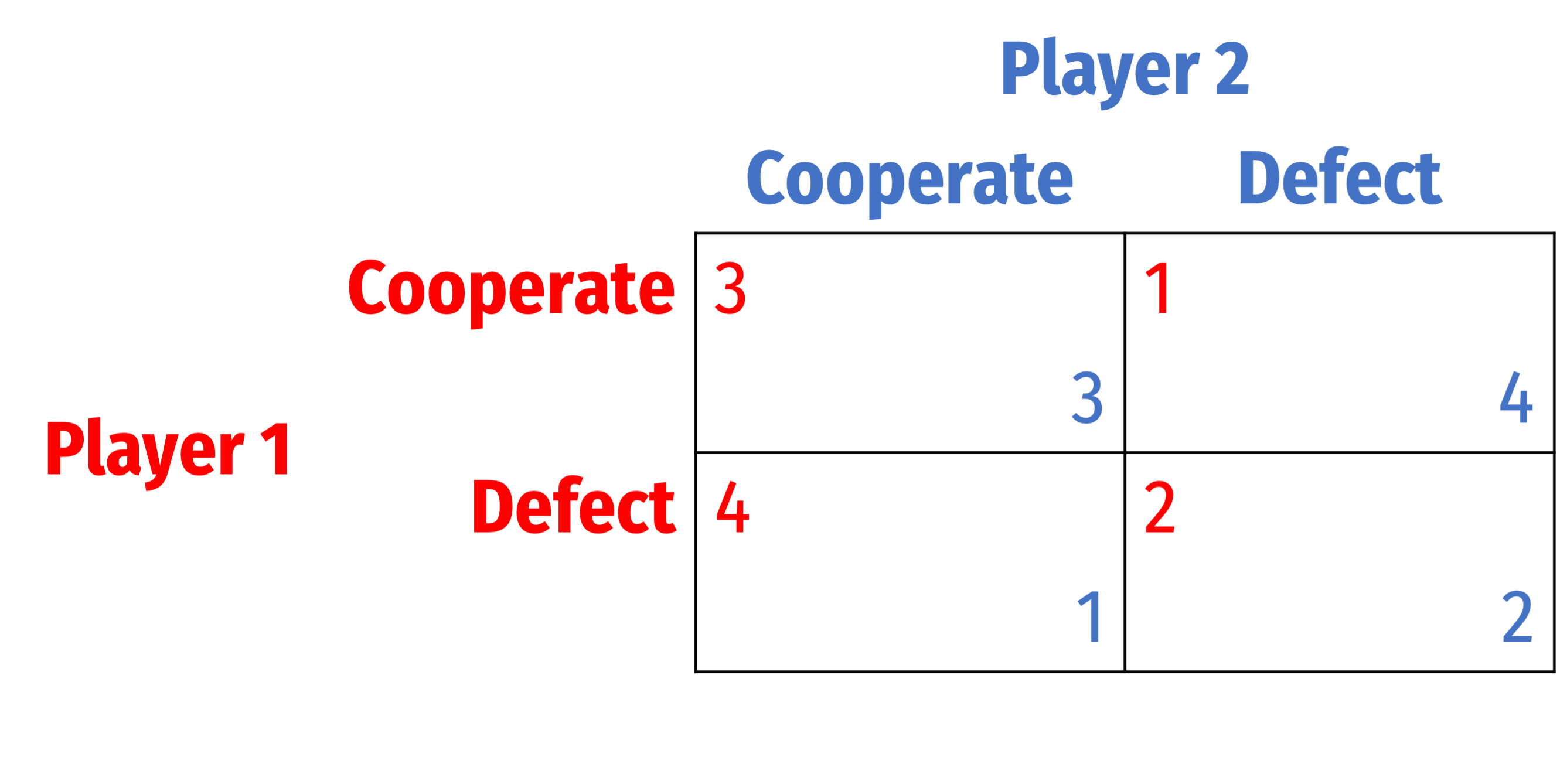

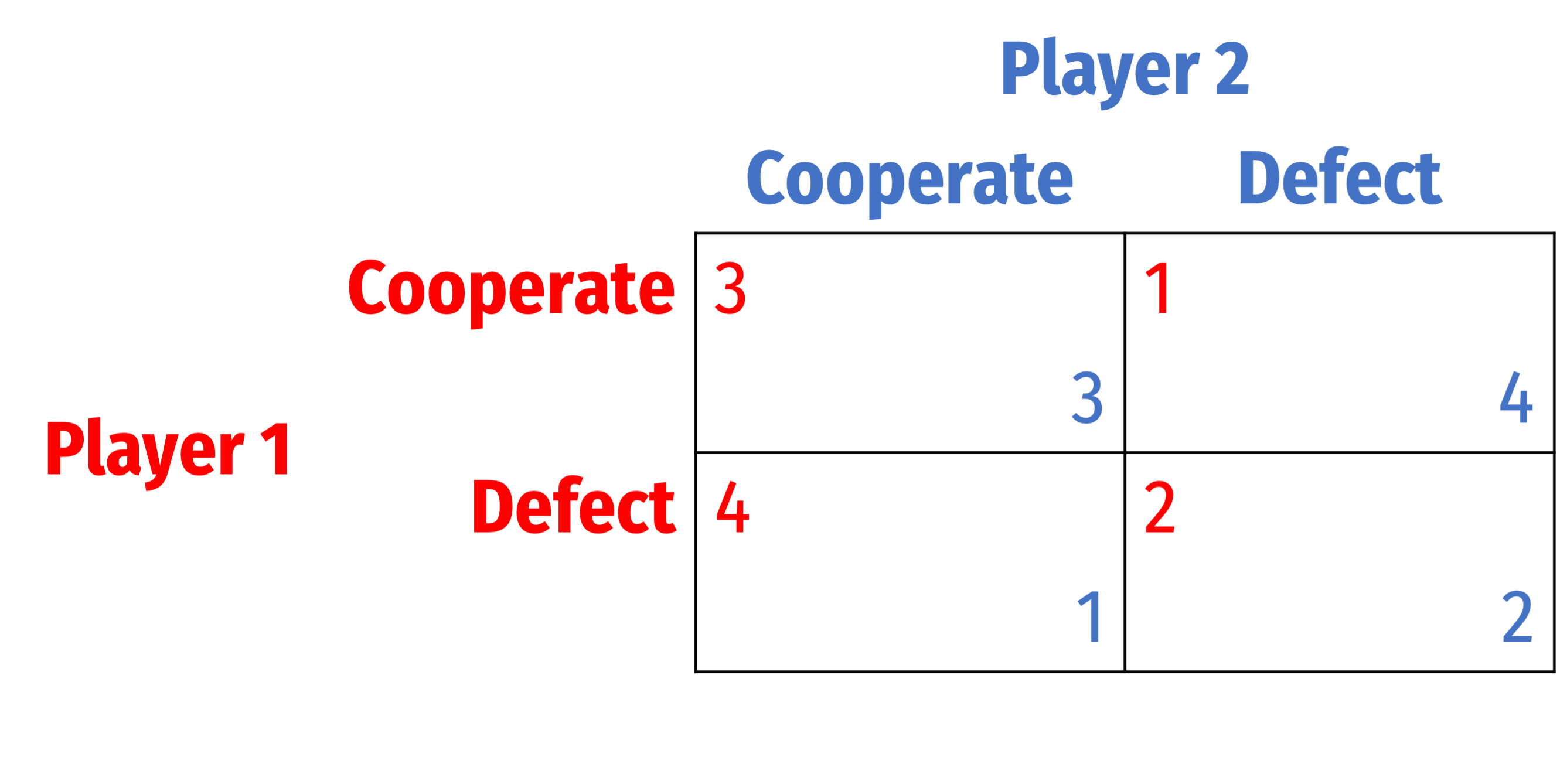

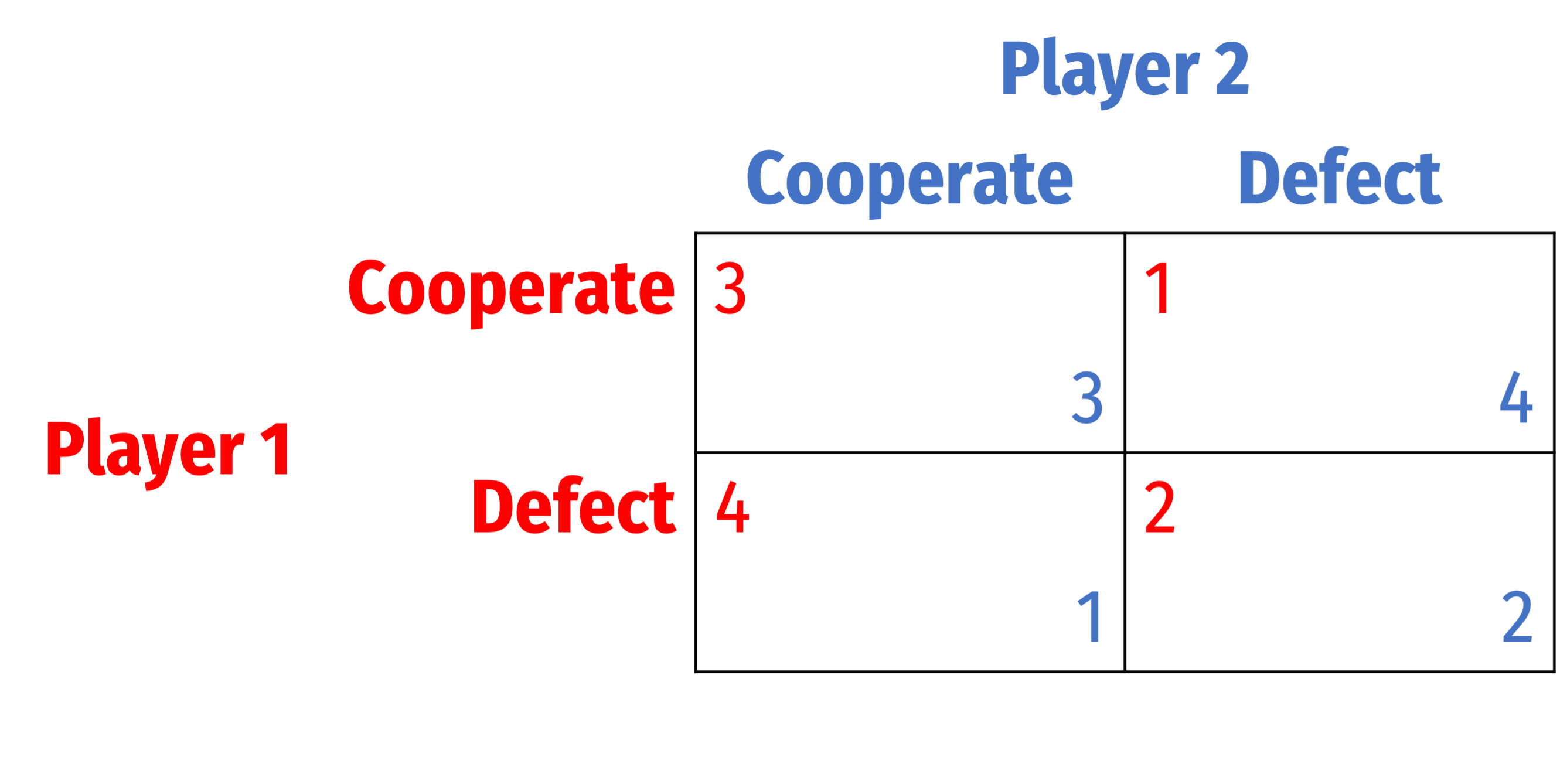

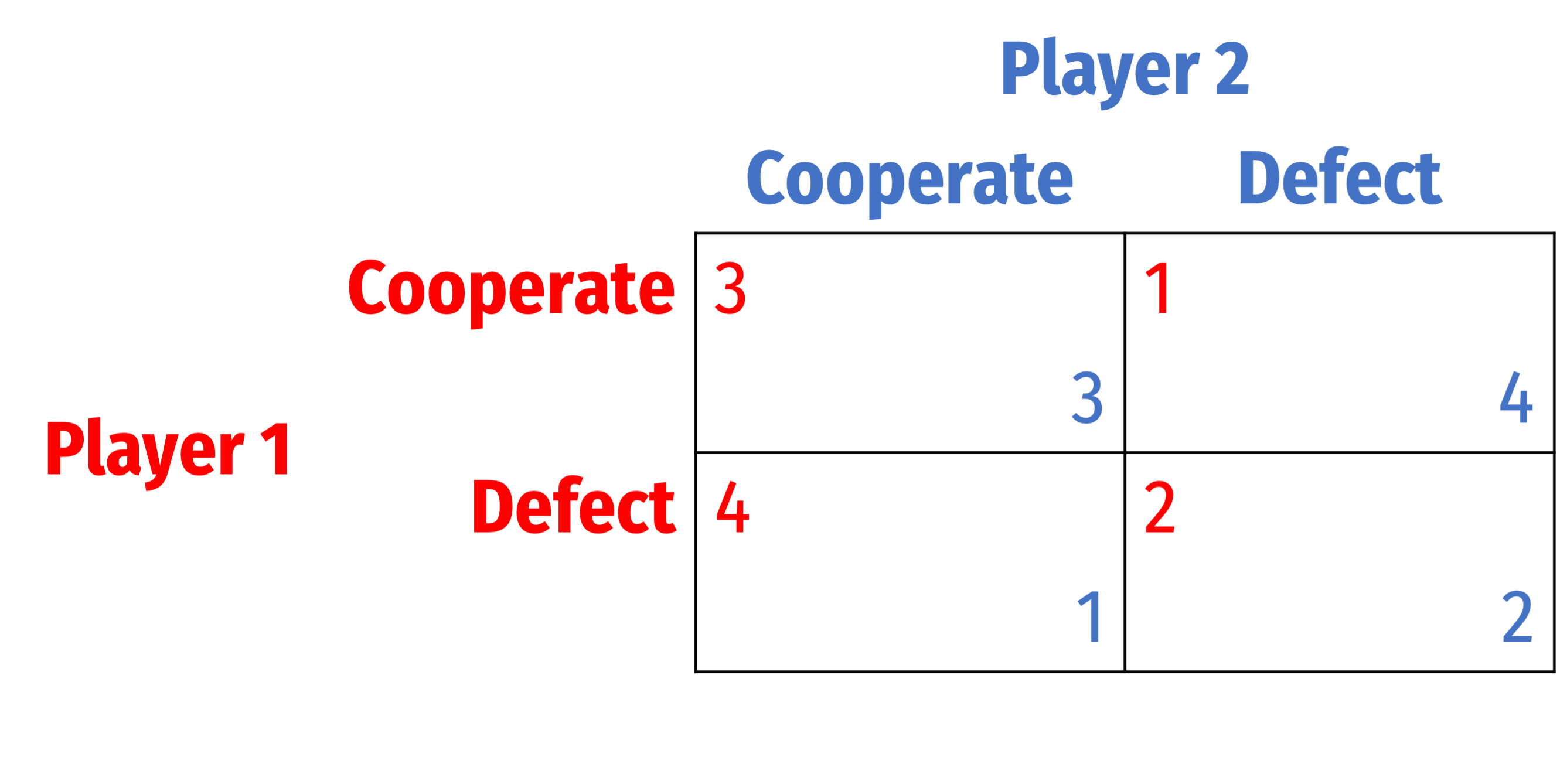

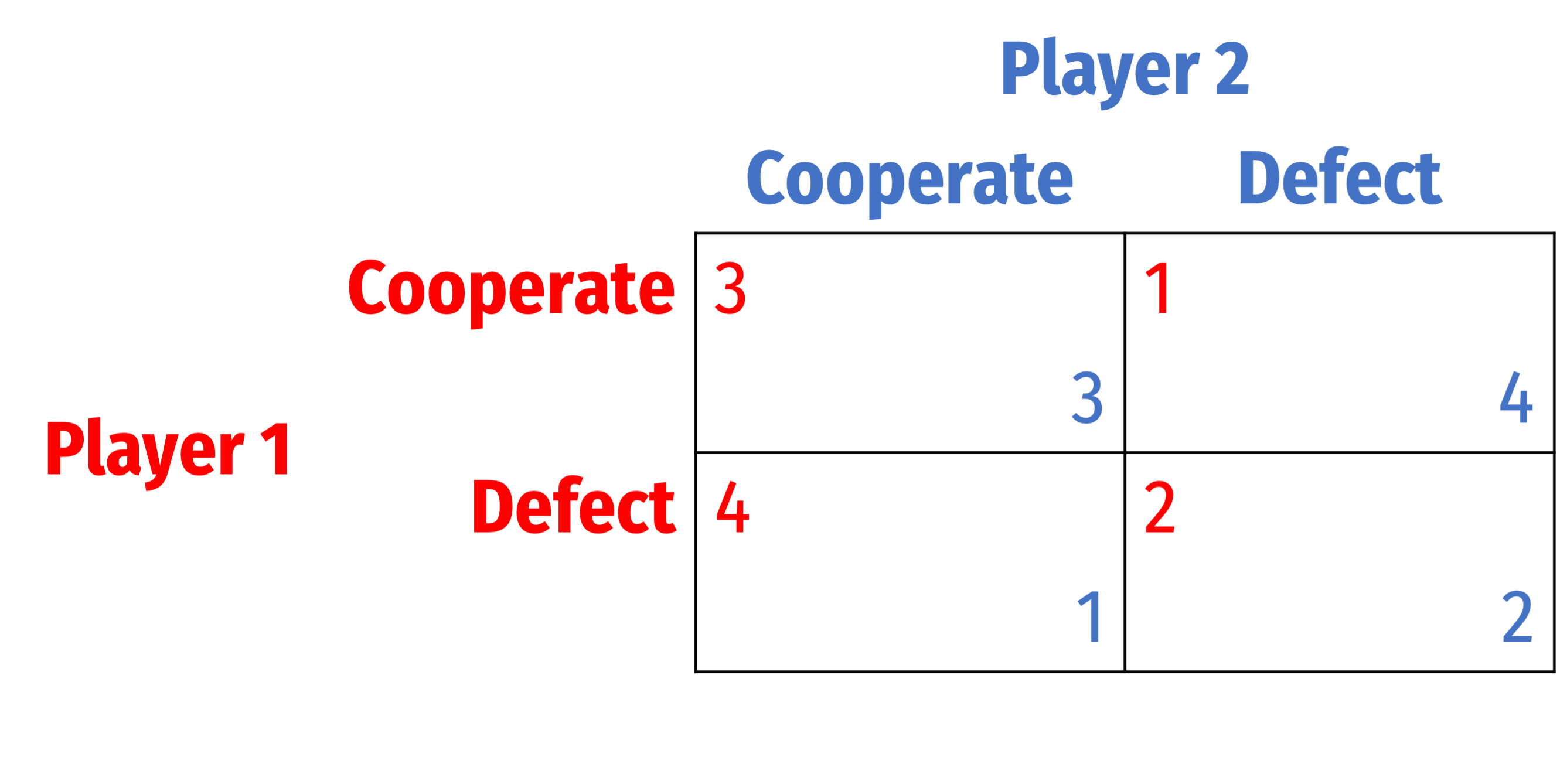

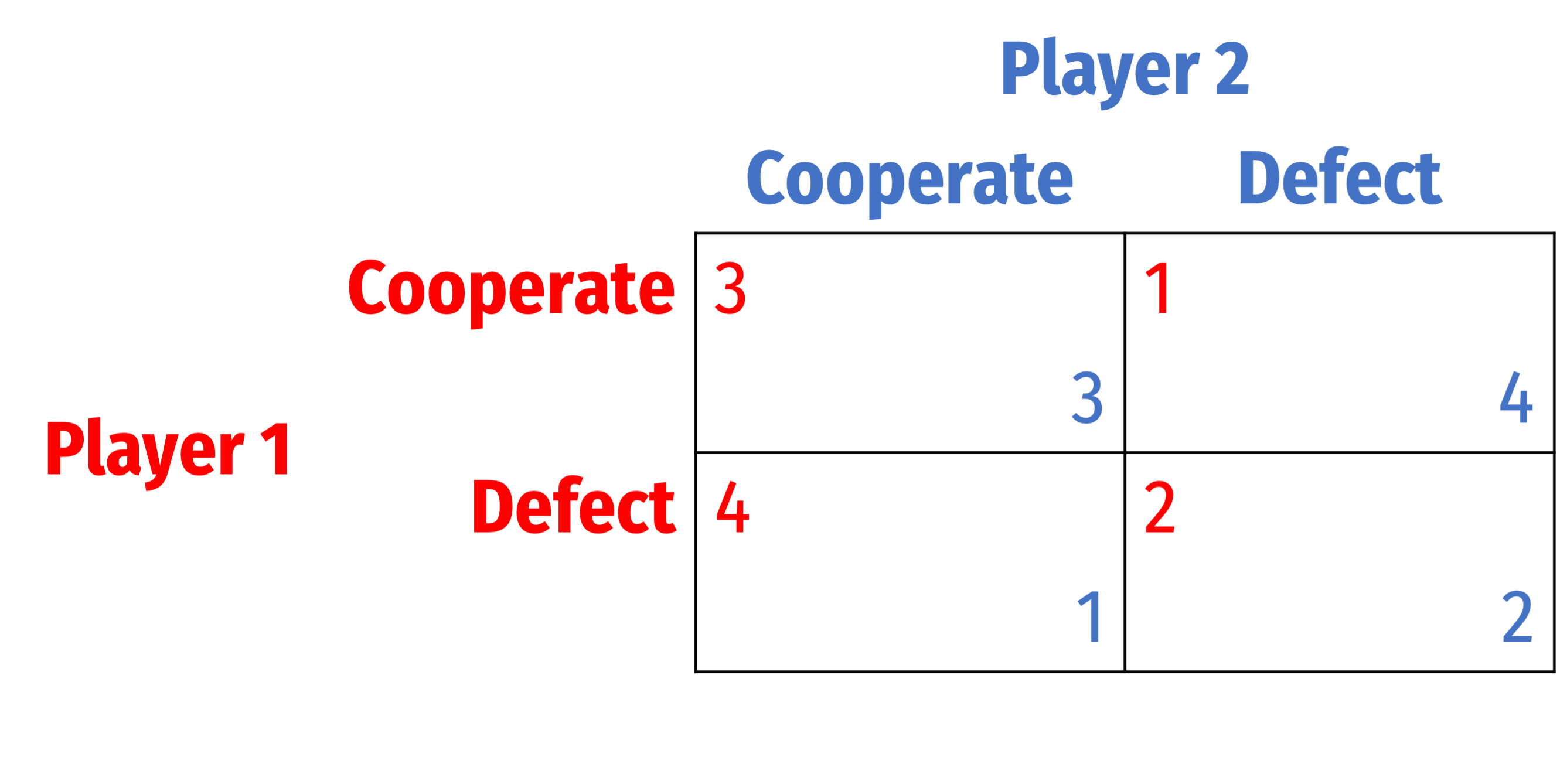

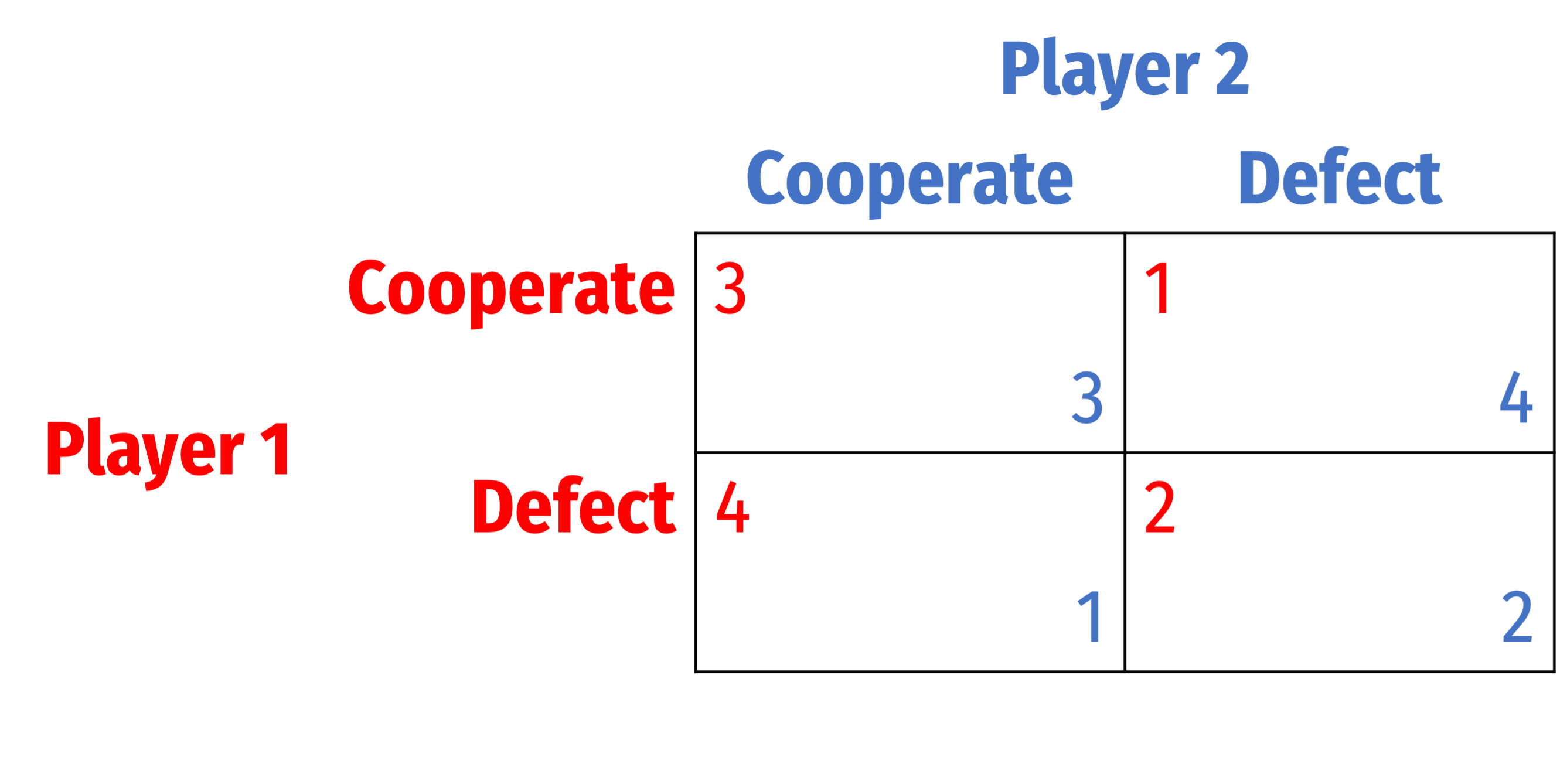

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Cooperators)

Consider first a population of Cooperators

Small fraction ϵ of mutants appear, who Defect

Among the large population, individuals randomly meet and interact

- Prob. of playing against normal (Cooperator): 1−ϵ

- Prob. of playing against mutant (Defector): ϵ

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Cooperators)

- We need to calculate the expected payoffs of:

- A “normal” individual facing another normal individual with probability (1−ϵ) and a mutant with probability ϵ

- A “mutant” individual facing a normal individual with probability (1−ϵ) and another mutant with probability ϵ

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Cooperators)

- Expected payoff to a normal (cooperator) type:

E[Cooperate]=3(1−ϵ)+1(ϵ)=3−2ϵ

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Cooperators)

Expected payoff to a normal (cooperator) type: E[Cooperate]=3(1−ϵ)+1(ϵ)=3−2ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (defector) type: E[Defect]=4(1−ϵ)+2(ϵ)=4−2ϵ

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Cooperators)

Expected payoff to a normal (cooperator) type: E[Cooperate]=3(1−ϵ)+1(ϵ)=3−2ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (defector) type: E[Defect]=4(1−ϵ)+2(ϵ)=4−2ϵ

Payoff to mutants > payoff to normal types

- Higher-fitness mutants (defectors) will successfully invade a population of cooperators

Therefore, cooperation is not ESS

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Defectors)

Consider next a population of Defectors

Small fraction ϵ of mutants appear, who Cooperate

Among the large population, individuals randomly meet and interact

- Prob. of playing against normal (Defector): 1−ϵ

- Prob. of playing against mutant (Cooperator): ϵ

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Defectors)

- Expected payoff to a normal (defector) type:

E[Defect]=2(1−ϵ)+4(ϵ)=2+2ϵ

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Defectors)

Expected payoff to a normal (defector) type: E[Defect]=2(1−ϵ)+4(ϵ)=2+2ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (cooperator) type: E[Cooperate]=1(1−ϵ)+3(ϵ)=1+2ϵ

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma (Defectors)

Expected payoff to a normal (defector) type: E[Defect]=2(1−ϵ)+4(ϵ)=2+2ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (cooperator) type: E[Cooperate]=1(1−ϵ)+3(ϵ)=1+2ϵ

Payoff to normal > payoff to mutants types

- Lower-fitness mutants (cooperators) cannot successfully invade a population of cooperators

Therefore, defect is an ESS

ESS in a Prisoners' Dilemma

Consider human society as a prisoners' dilemma

All of us cooperating ≻ all of us defecting

- Cooperation is not ESS: a single defector can exploit a world of cooperators

- Defection is ESS: it's dangerous to be the only cooperator in a world of defectors

“I can picture in my mind a world without war, a world without hate. And I can picture us attacking that world because they'd never expect it.” — Jack Handey

- In human social settings, institutions allow us to credibly commit to cooperating

Implications for Biology and Game Theory

A dominated strategy cannot be evolutionarily stable

- e.g. Cooperate in prisoners' dilemma

Evolution can be inefficient

- e.g. prisoners' dilemma leads to (Defect, Defect) outcome

If a strategy, s is an ESS, then (s,s) must be a Nash equilibrium

- monomorphic equilibria require symmetric (s,s) ESS Nash equilibria

- the converse is not true

The Hawk-Dove Game

The Hawk-Dove Game

Hawk-dove game is the first example biologists studied

Game is not played by two animals of different species (i.e. an actual hawk and an actual dove)

Game is played by members of the same species playing different behavioral strategies (phenotypes)

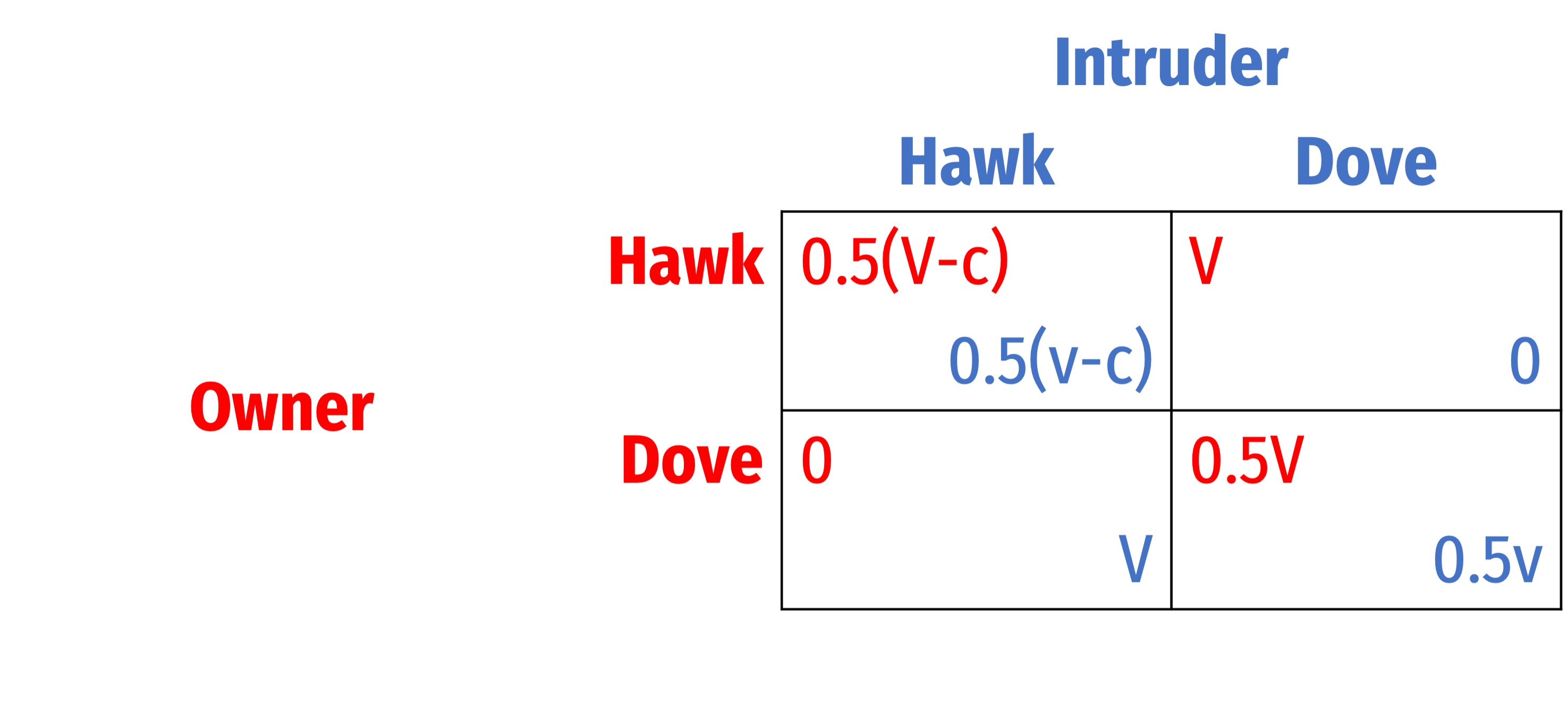

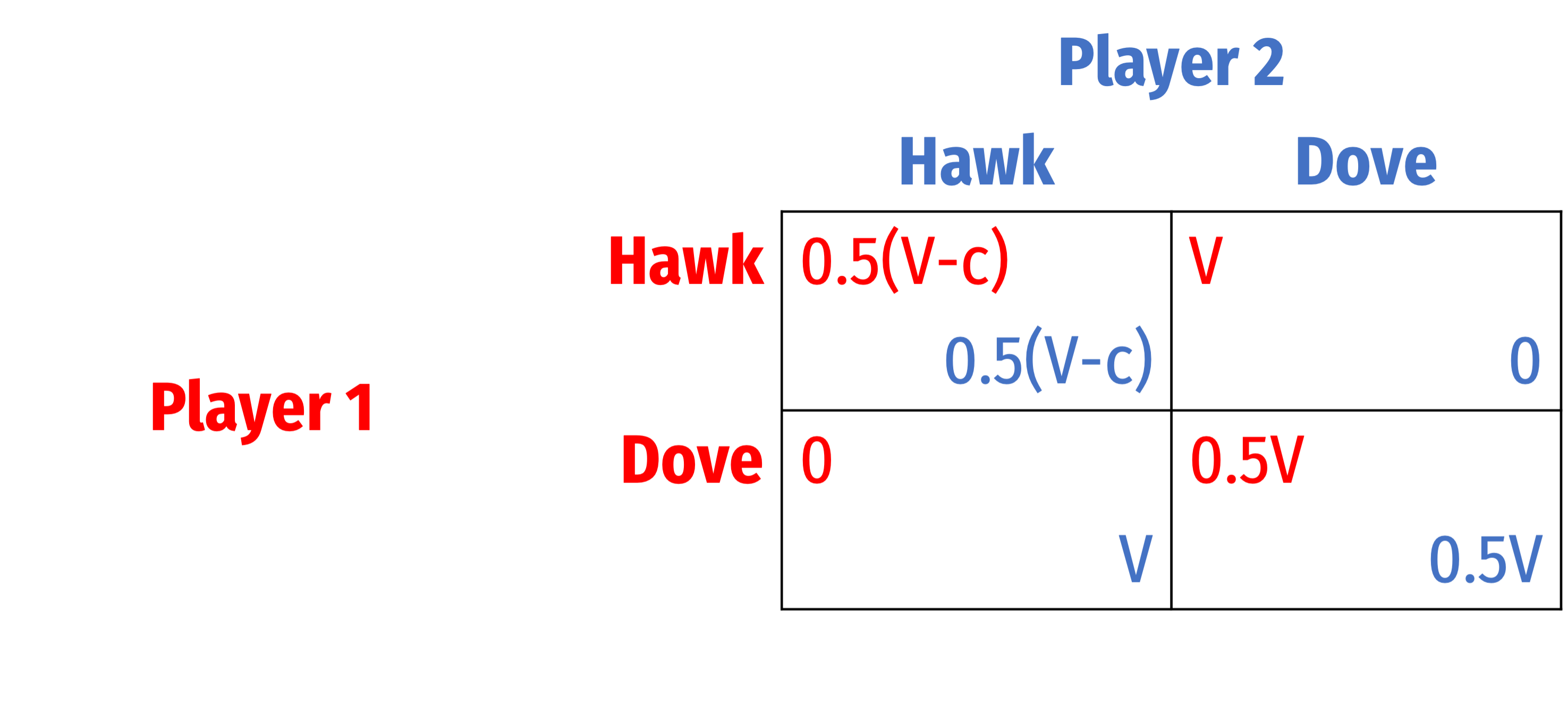

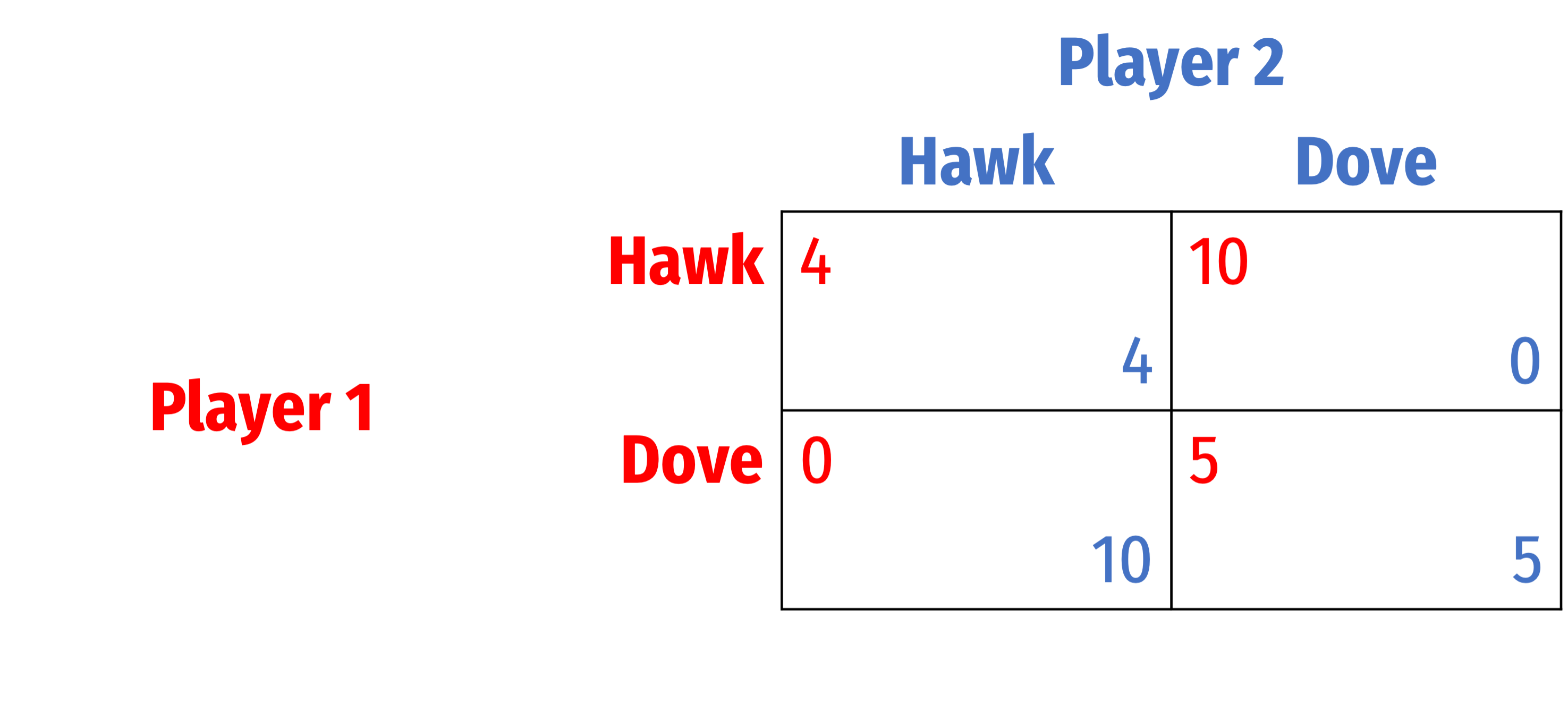

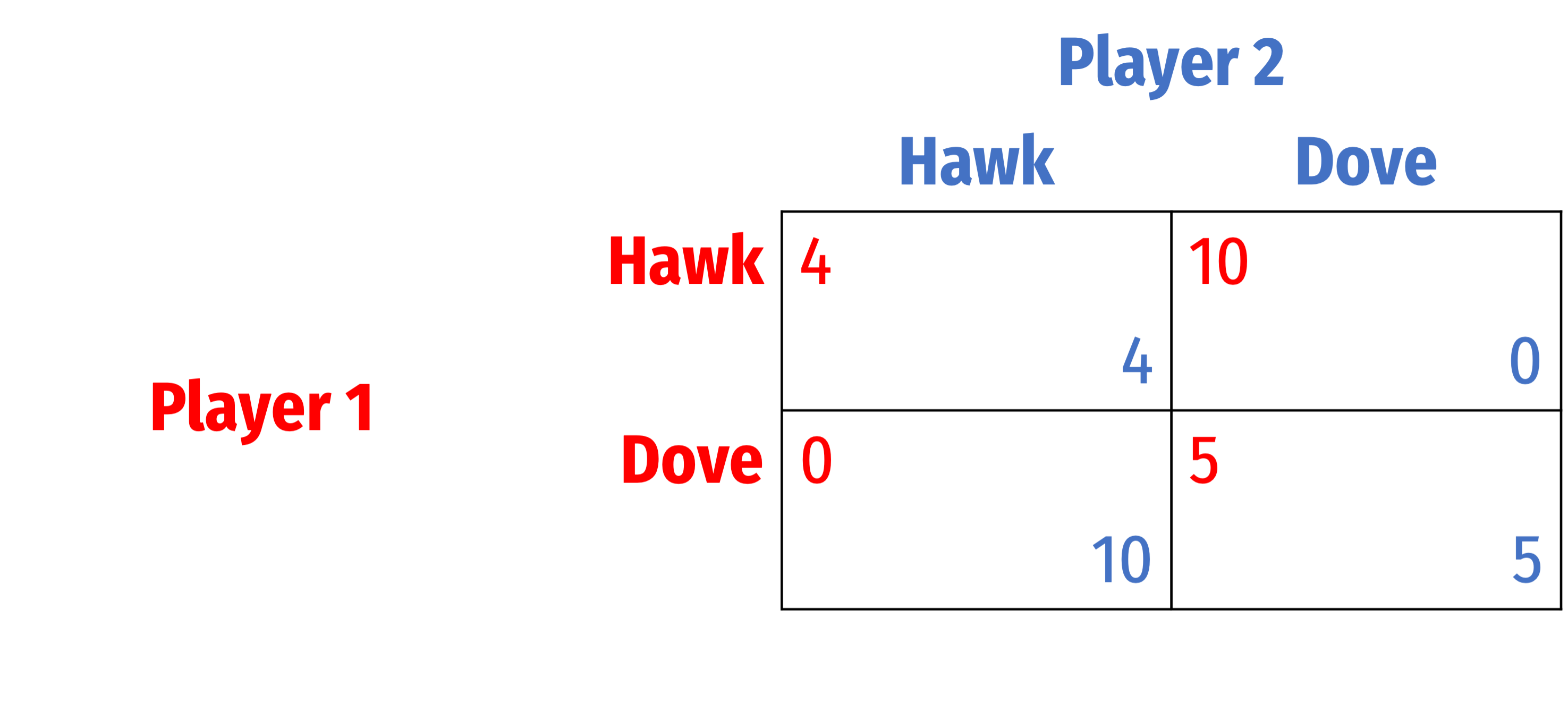

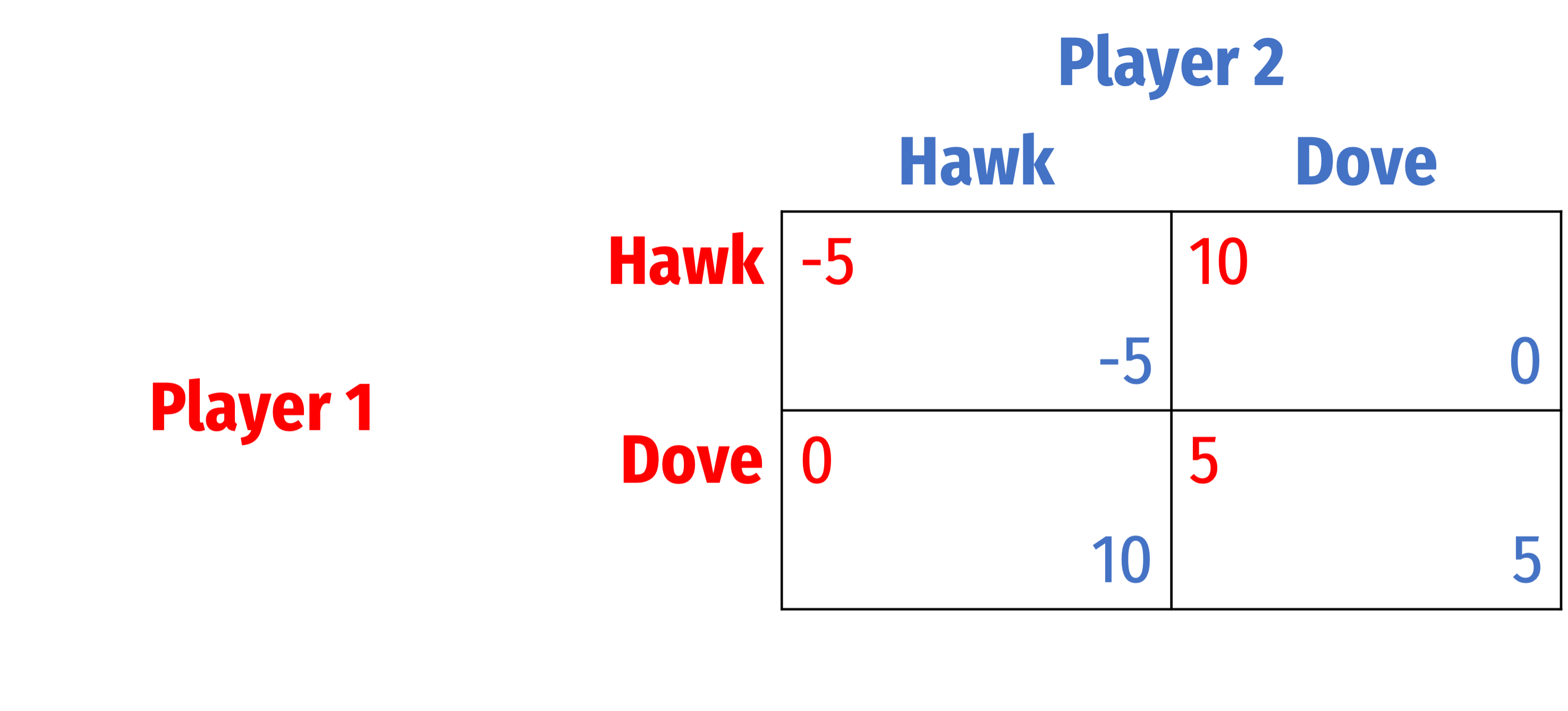

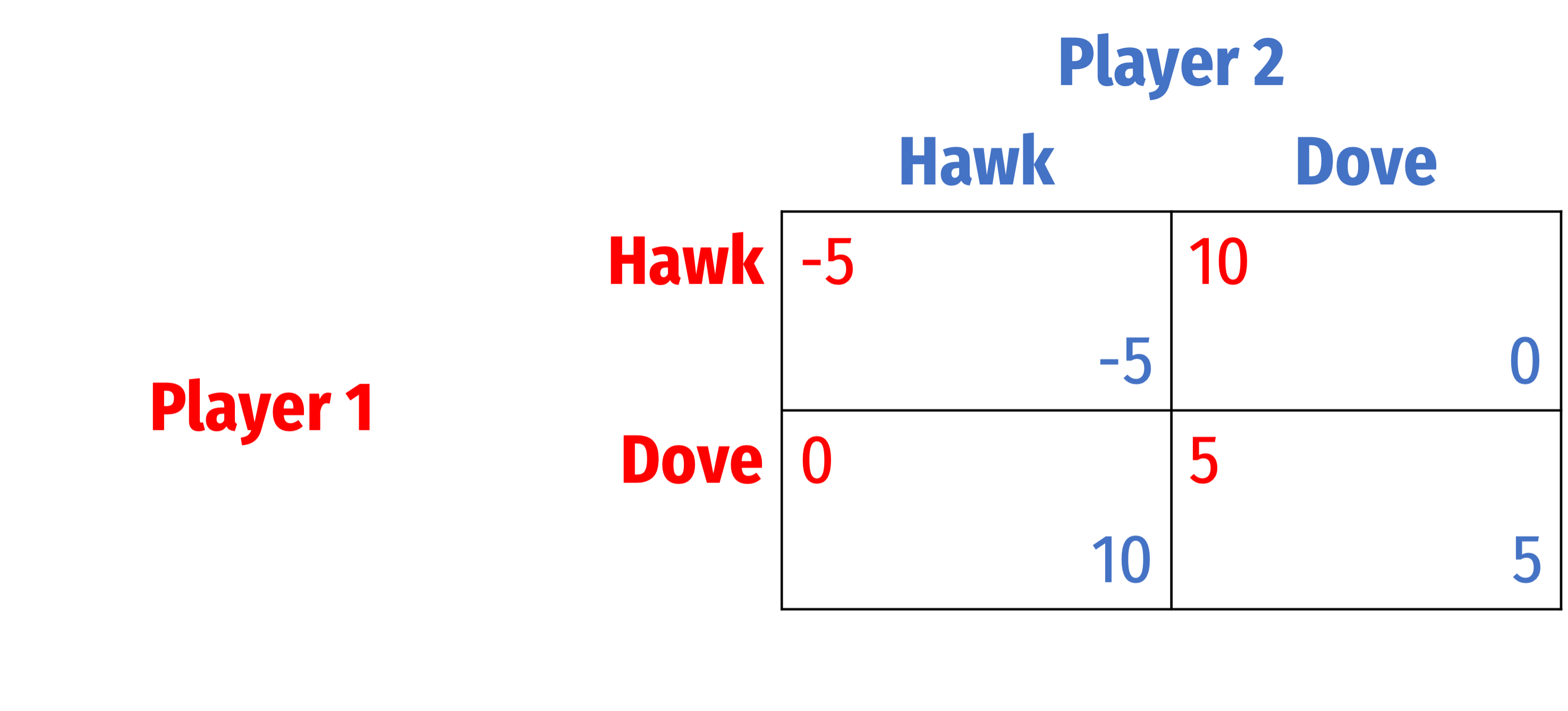

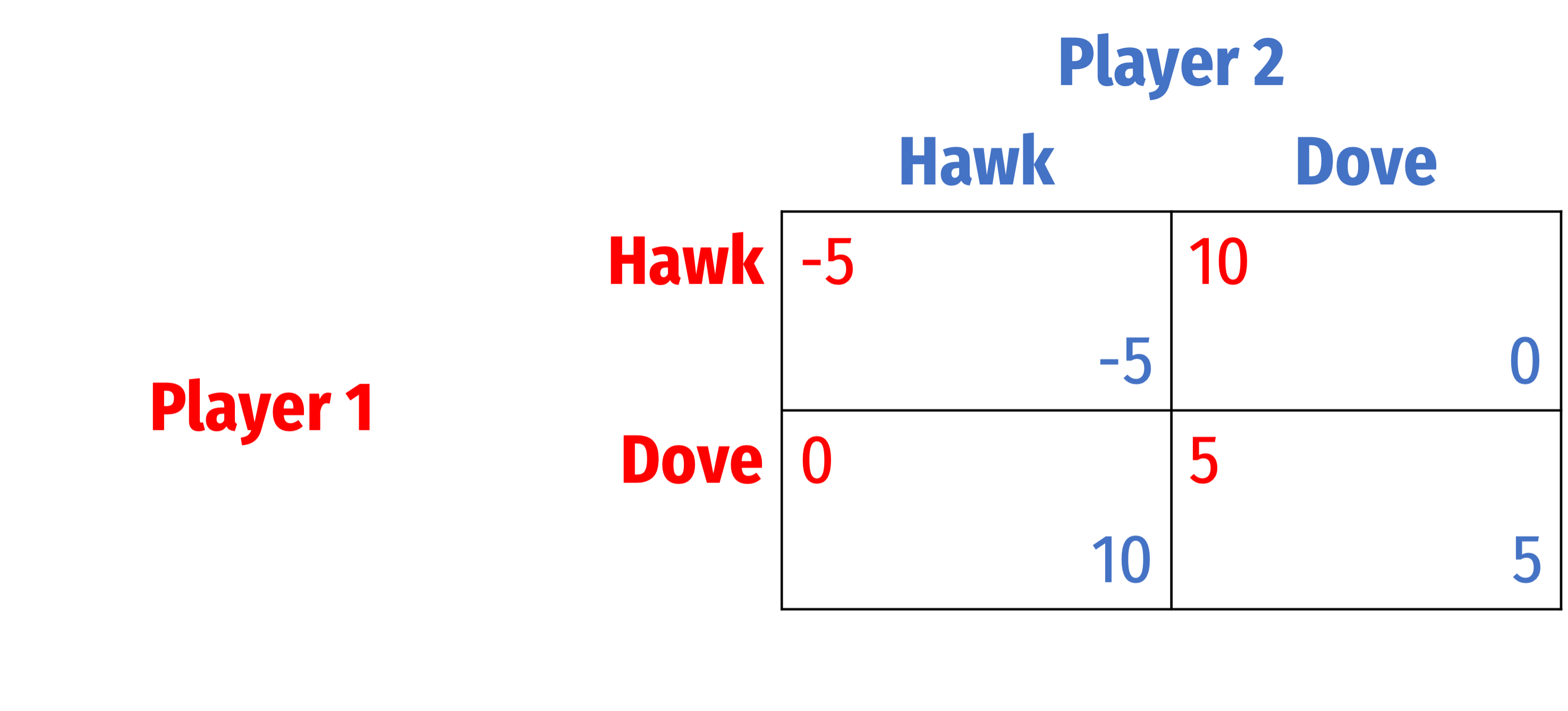

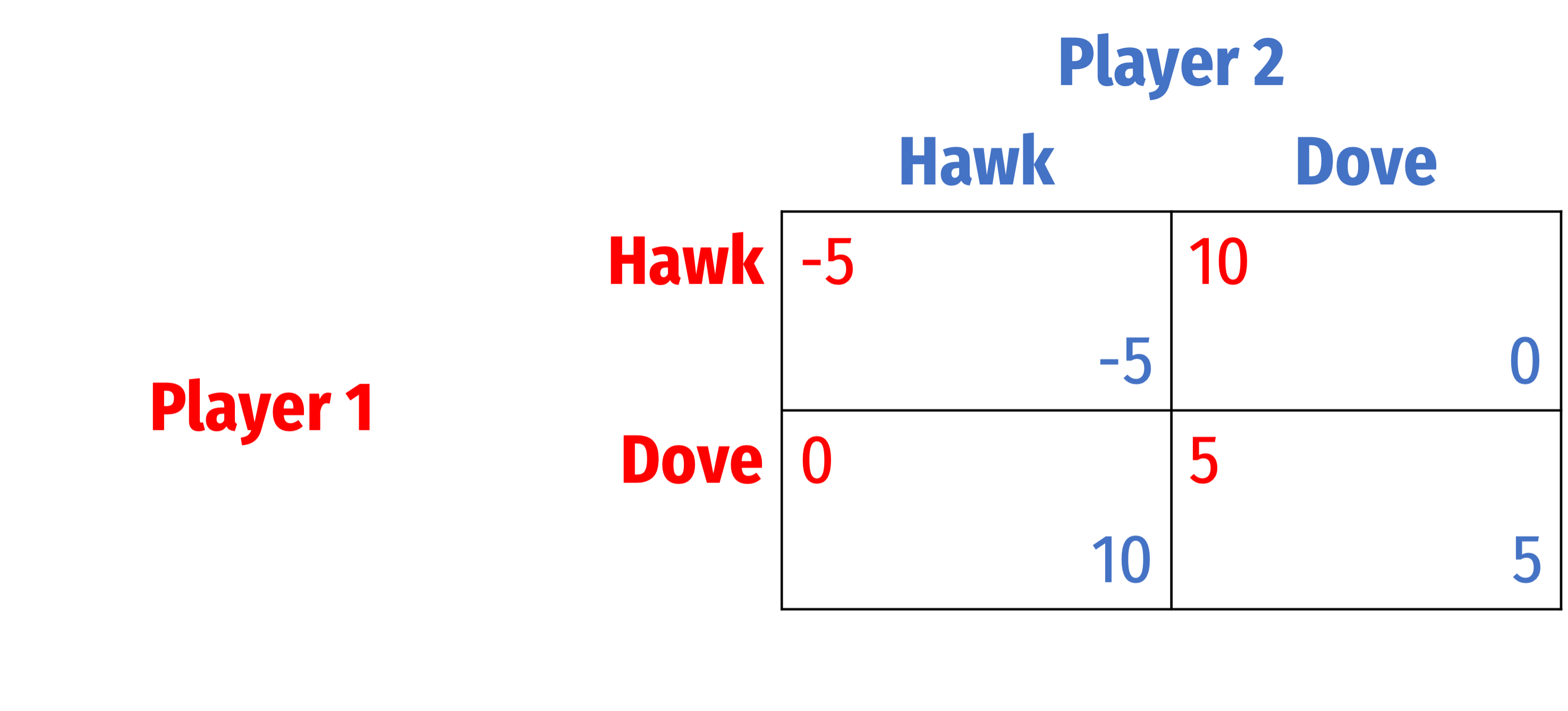

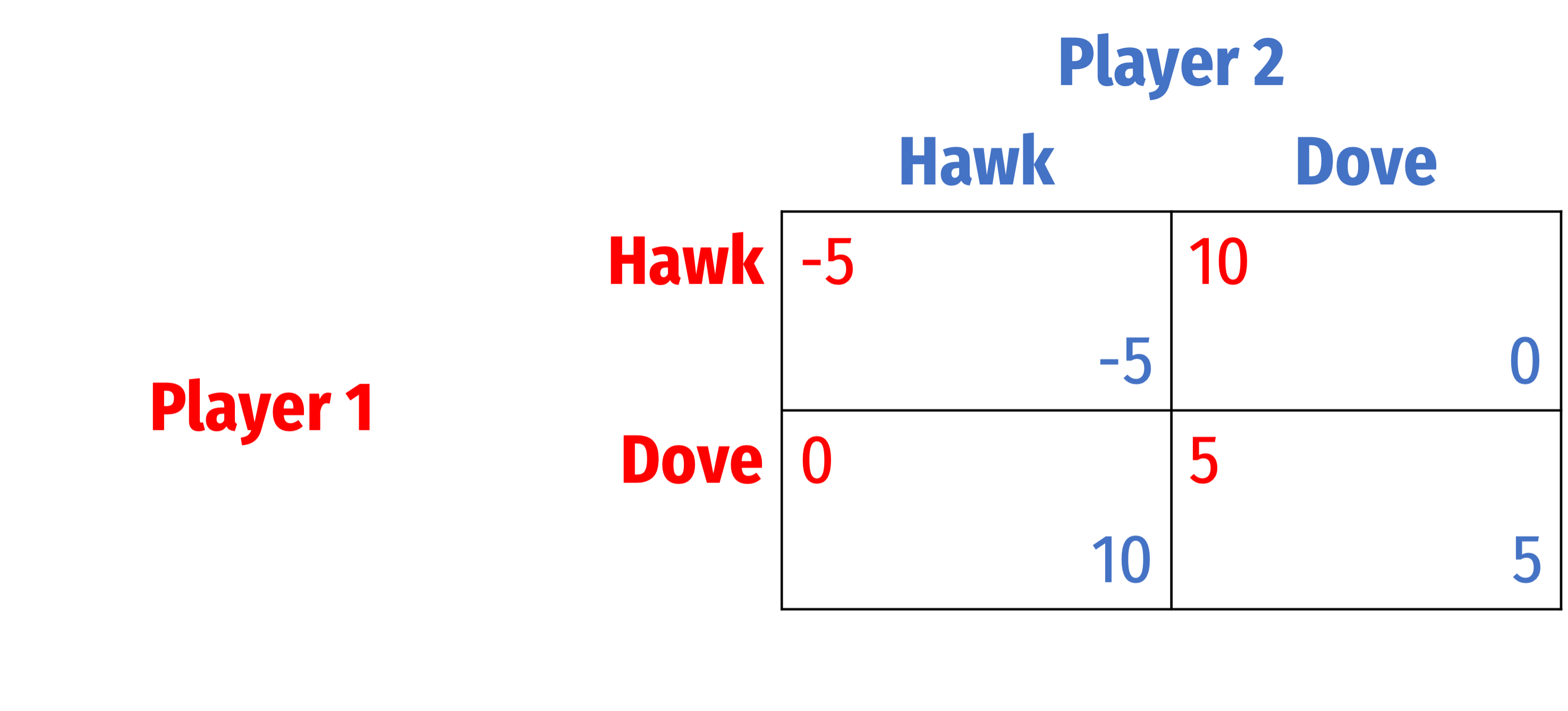

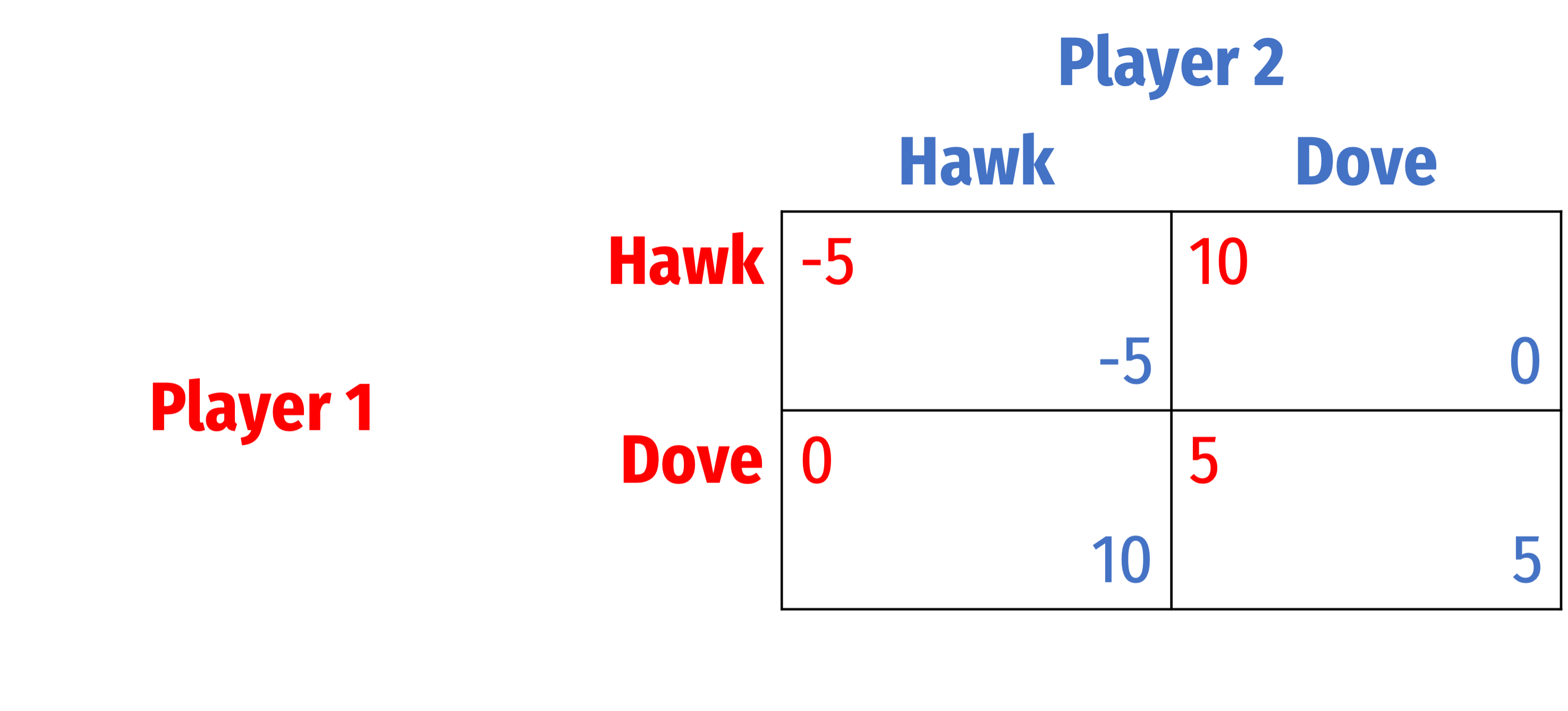

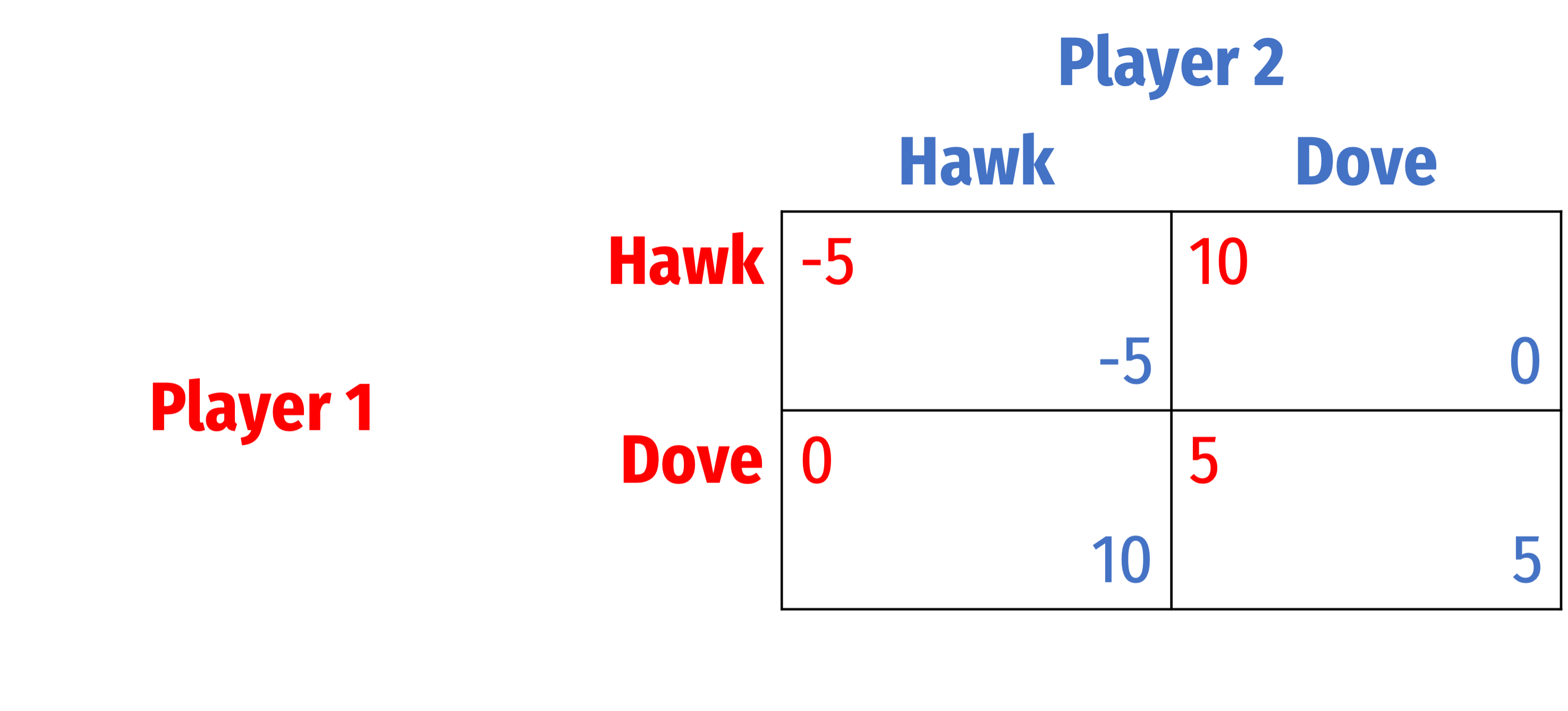

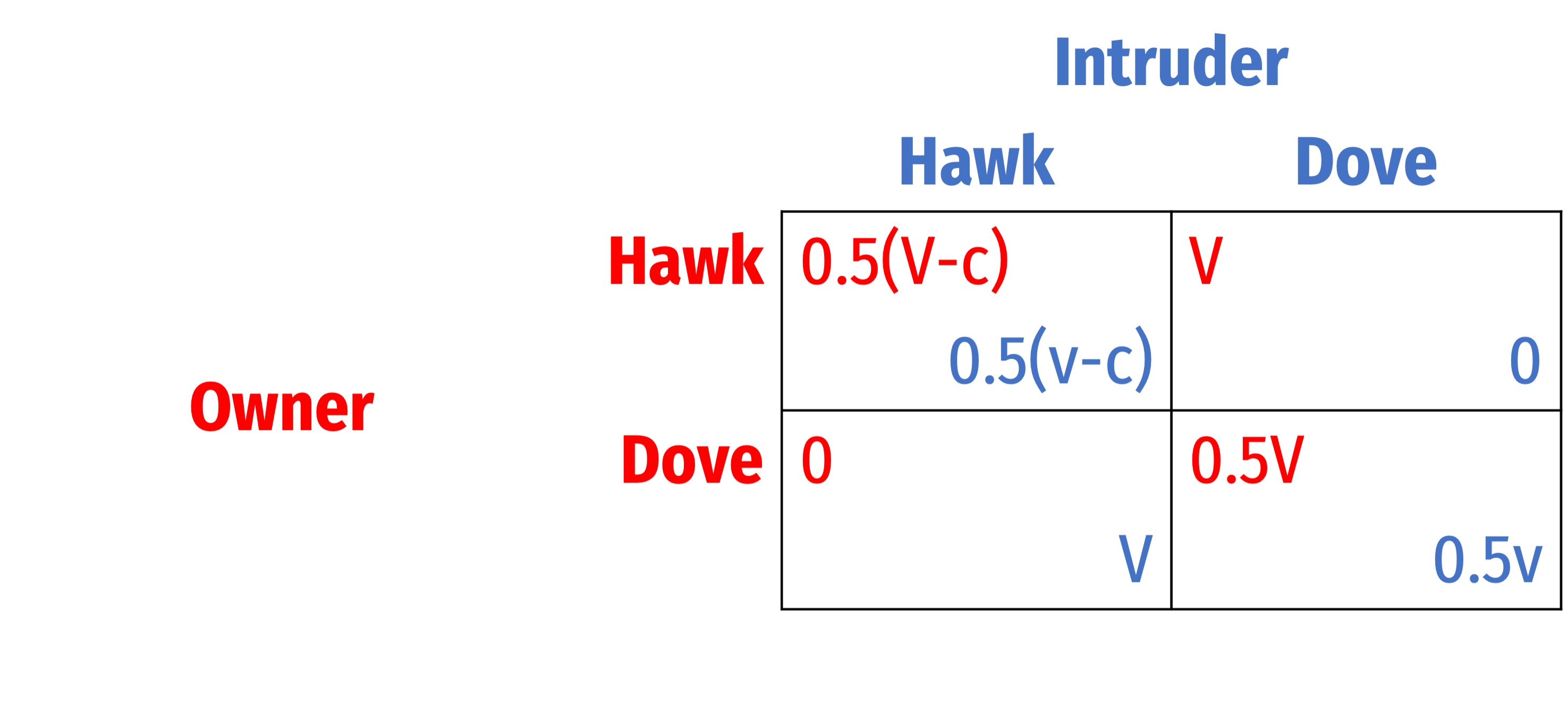

The Hawk-Dove Game: General Form

Two individuals competing over scarce resource: V

- V≈ gain in the animal’s fitness

“Dove” strategy is passive, yields entire resource to “Hawk”

“Hawk” strategy is aggressive, fights for V

Two Doves meeting will share the resource, each getting 0.5V

Two Hawks meeting will fight

- Each animal is equally likely to win (p=0.50) and get V, or lose and get injured at cost −c, expected payoff is 0.5(V−c)

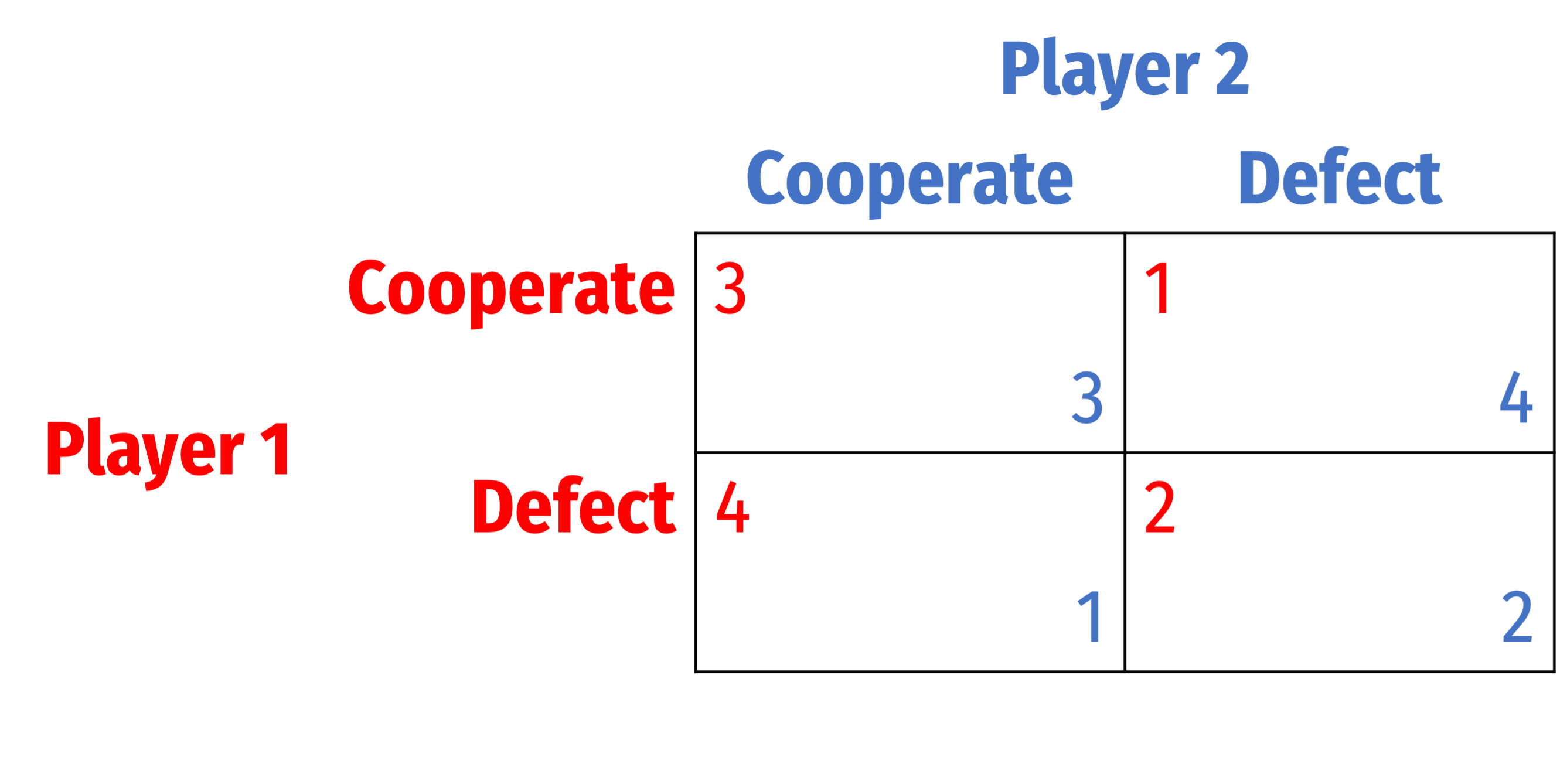

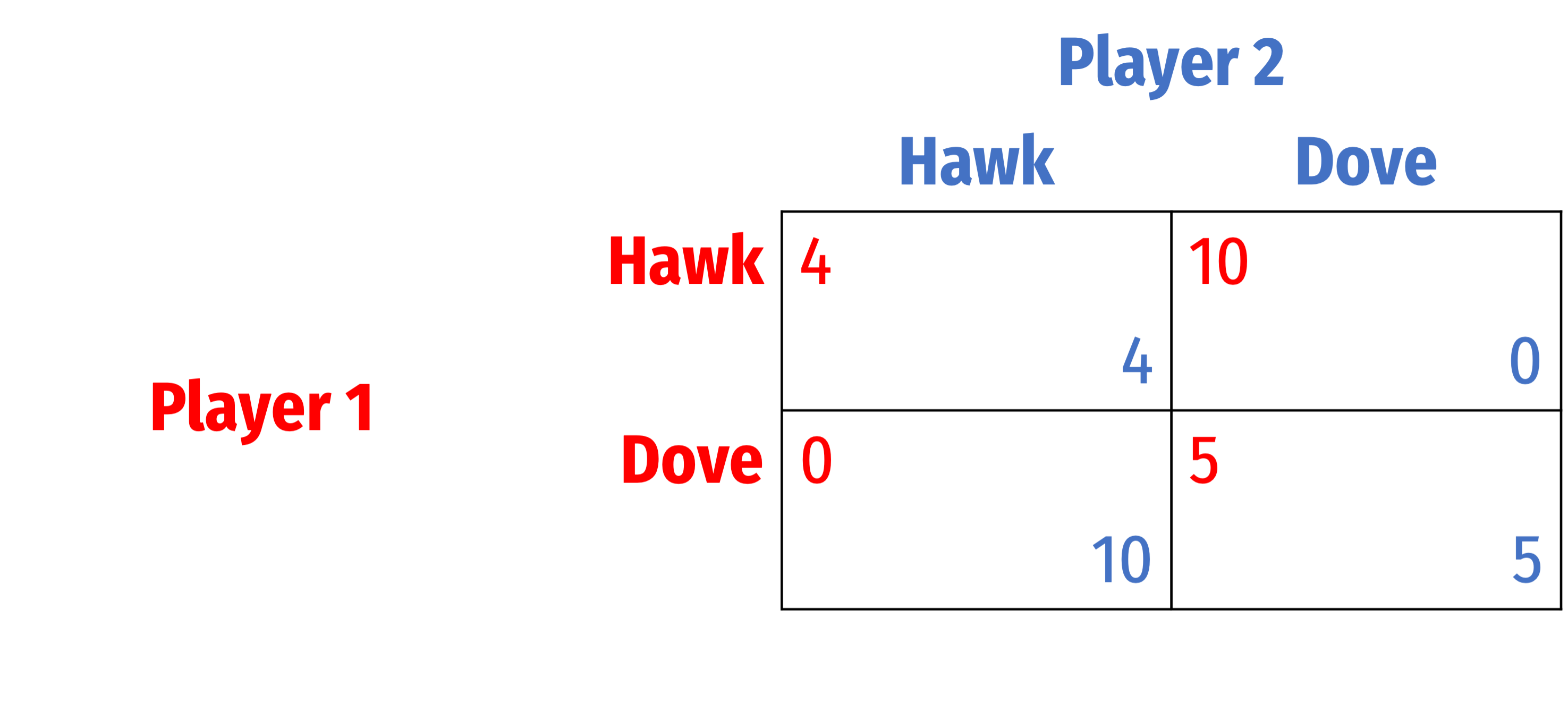

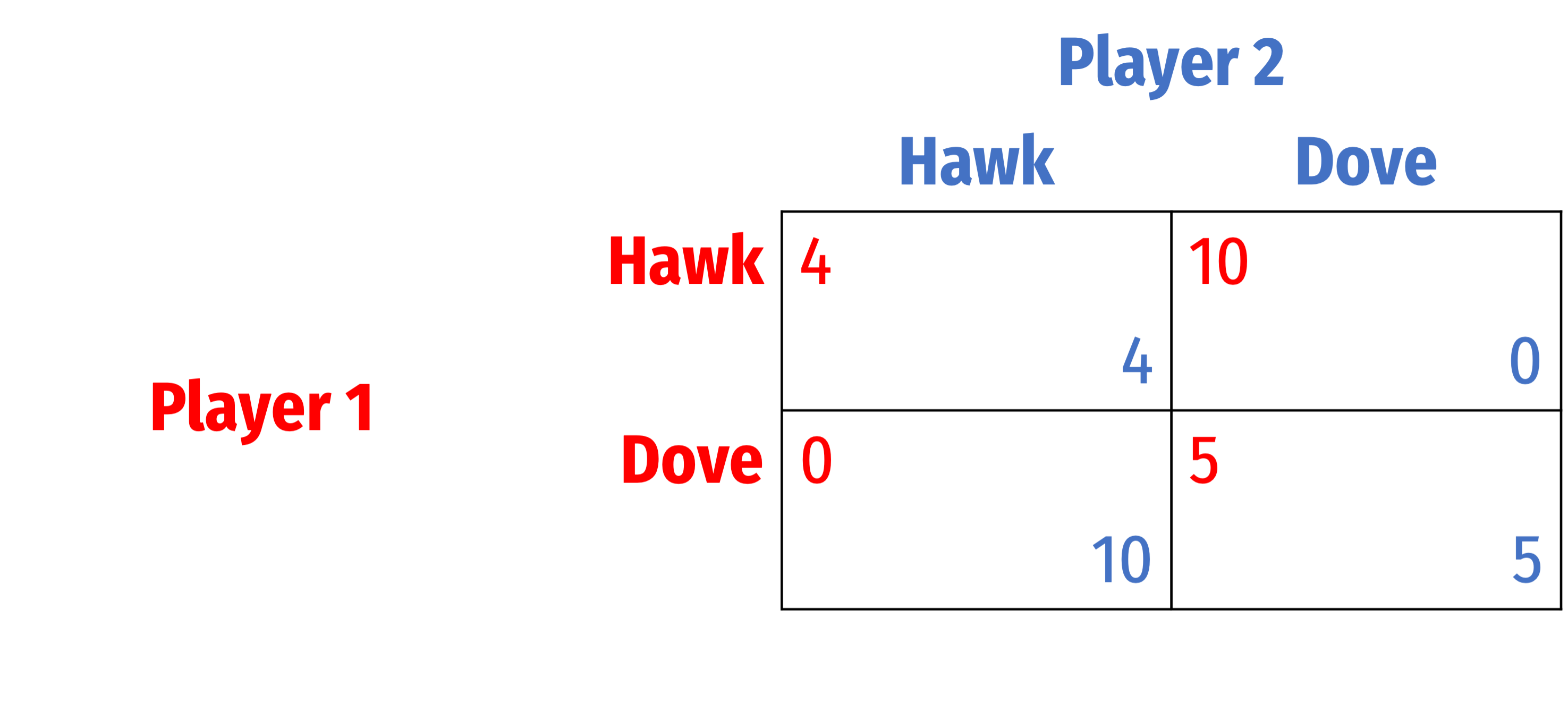

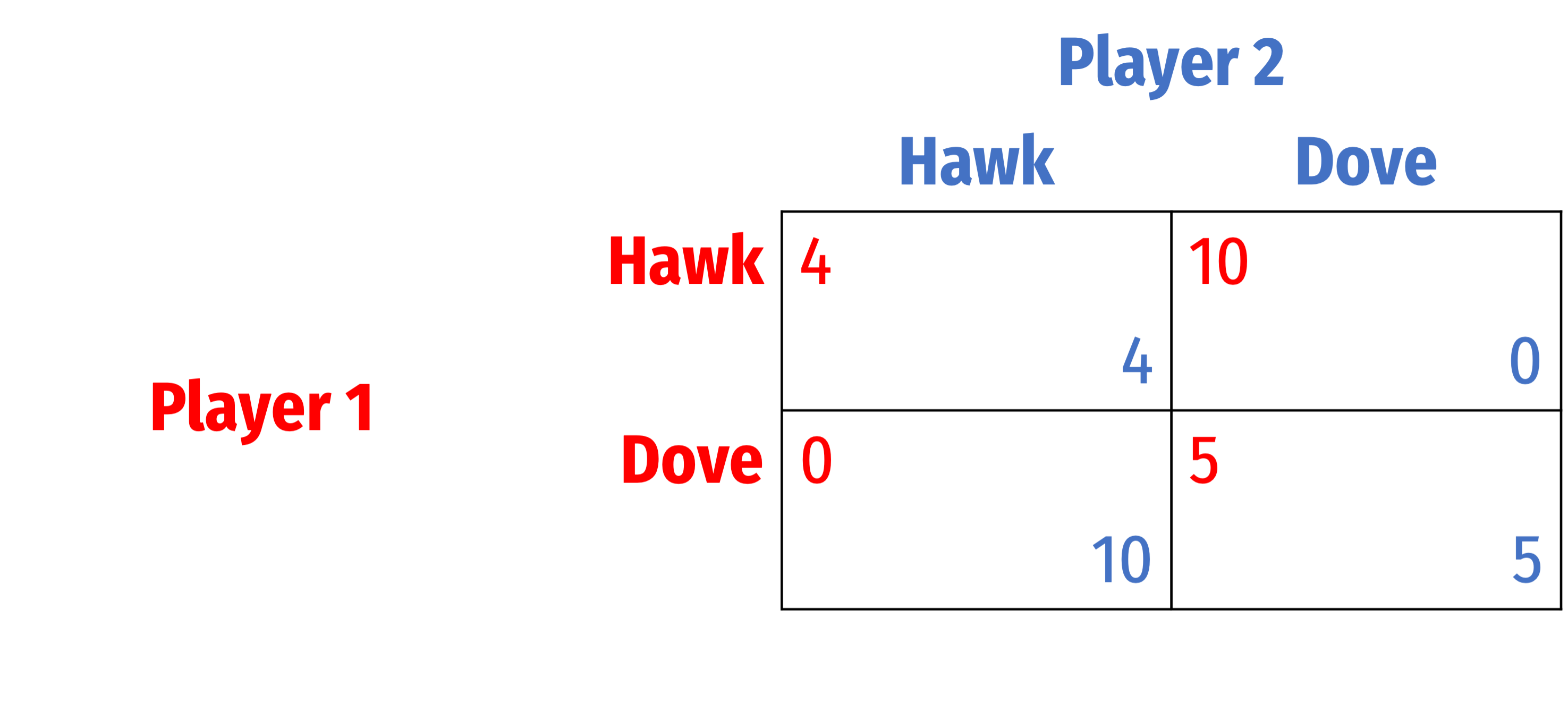

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Let V=10, c=2

“Hawk” ⟹ “Defect”

“Dove” ⟹ “Cooperate”

Dominant strategy to play Hawk

What type of game is this? (Look at the payoffs)

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=4(1−ϵ)+10(ϵ)=4+6ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=4(1−ϵ)+10(ϵ)=4+6ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (Dove) type: E[Dove]=0(1−ϵ)+5(ϵ)=5ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=4(1−ϵ)+10(ϵ)=4+6ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (Dove) type: E[Dove]=0(1−ϵ)+5(ϵ)=5ϵ

Hawk is ESS, a monomorphic population (all Hawks)

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Dove who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Dove who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Dove) type: E[Dove]=5(1−ϵ)+0(ϵ)=5−5ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Dove who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Dove) type: E[Dove]=5(1−ϵ)+0(ϵ)=5−5ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (Hawk) type: E[Dove]=10(1−ϵ)+4(ϵ)=10−6ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V>C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Dove who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Dove) type: E[Dove]=5(1−ϵ)+0(ϵ)=5−5ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (Hawk) type: E[Dove]=10(1−ϵ)+4(ϵ)=10−6ϵ

Dove is not ESS, will be invaded by Hawks!

This game is a prisoners' dilemma (when V>C)!

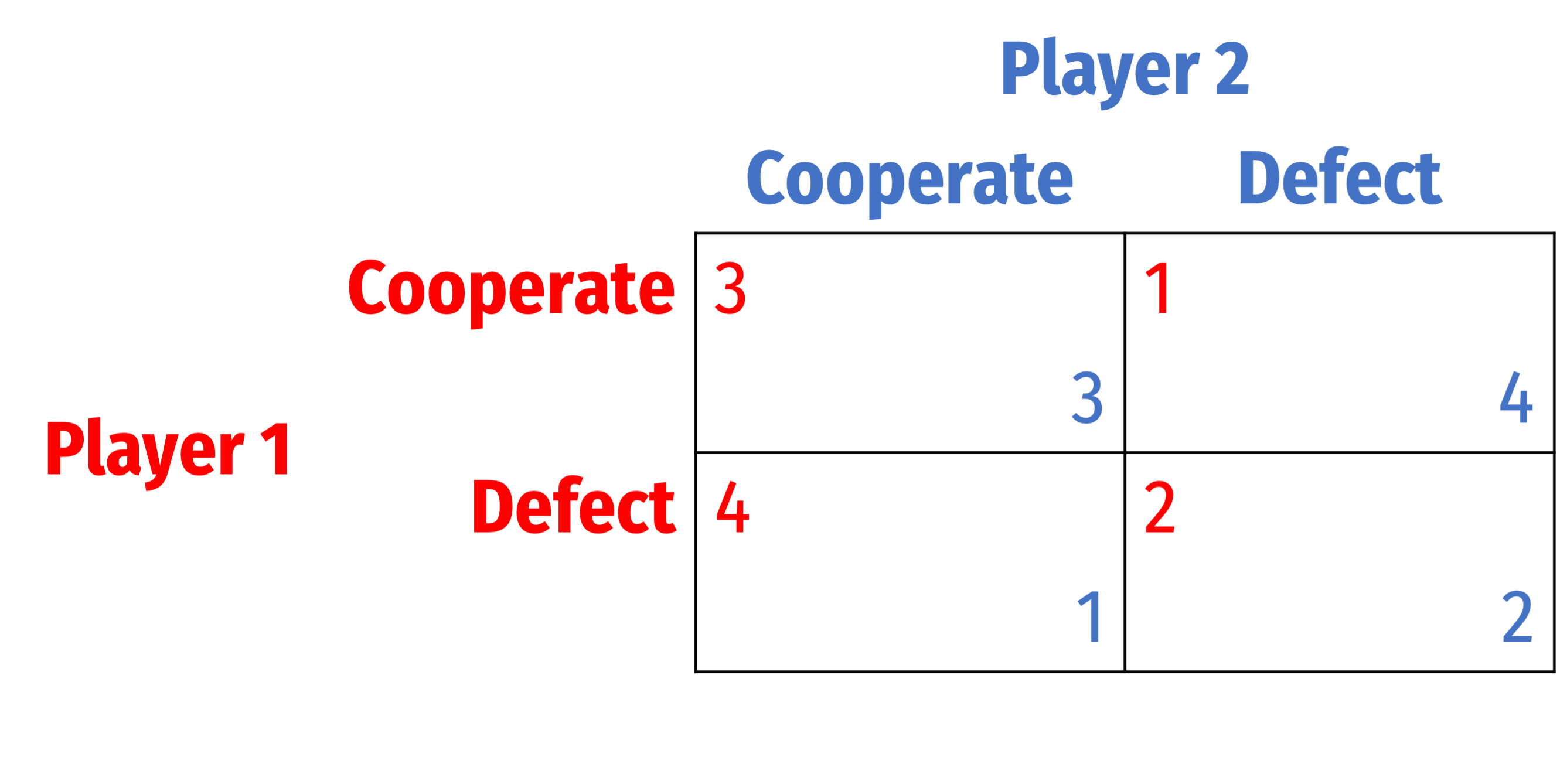

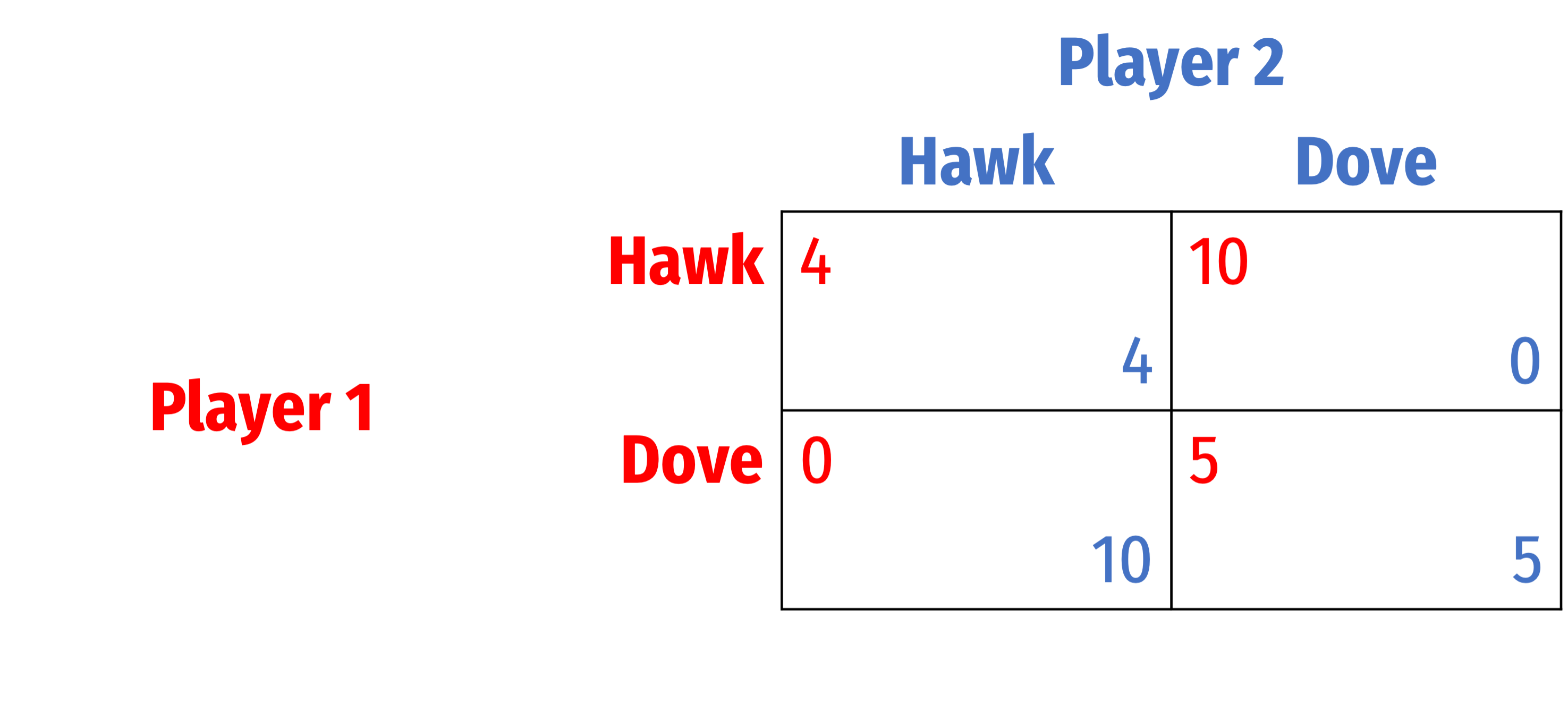

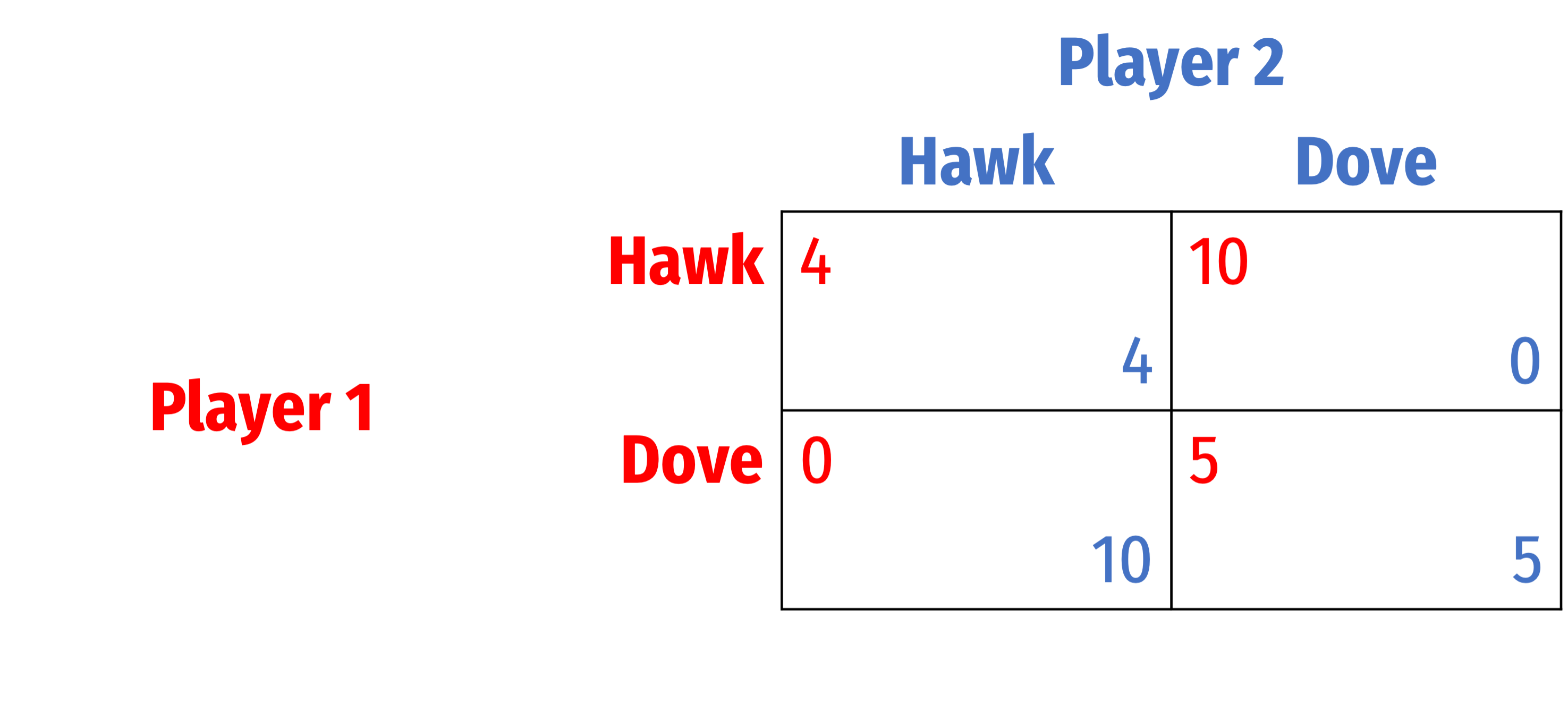

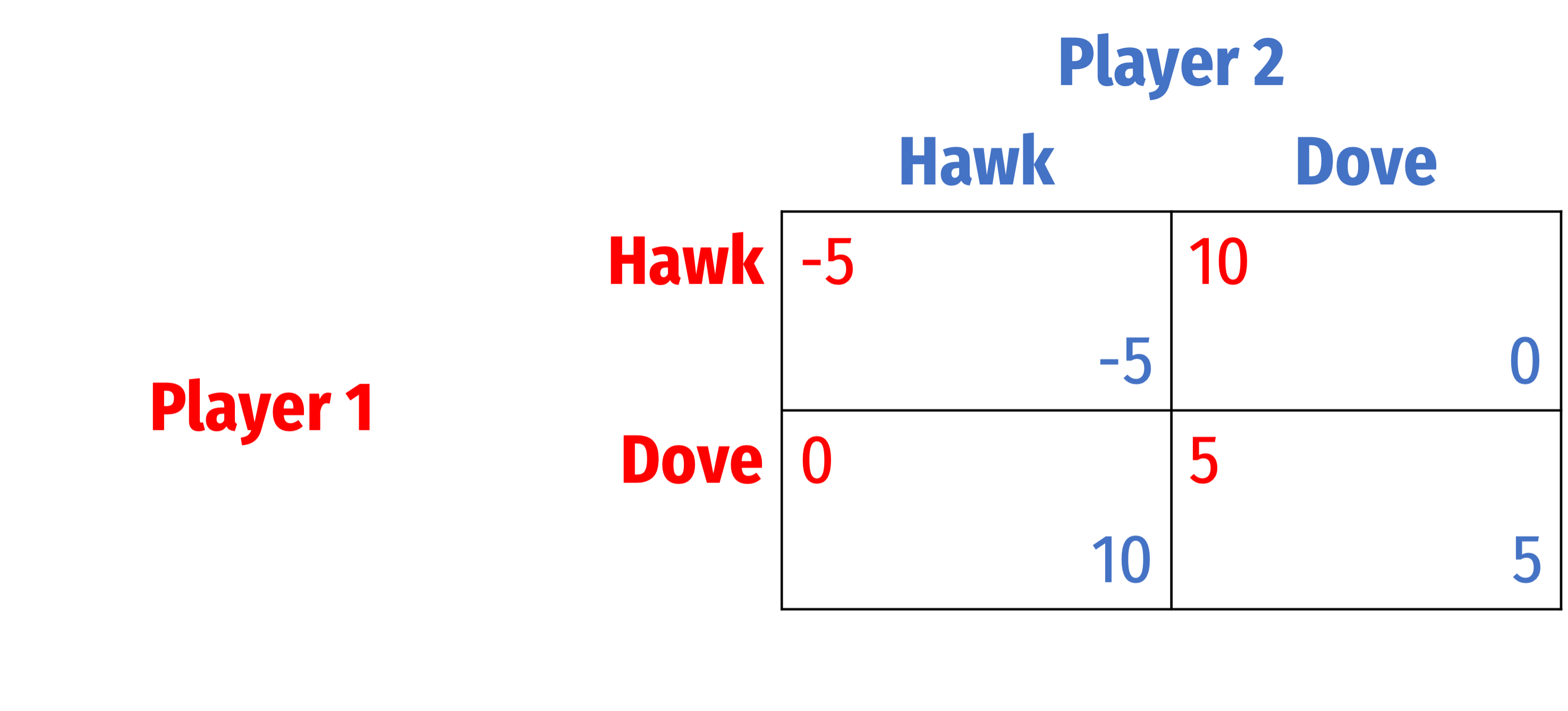

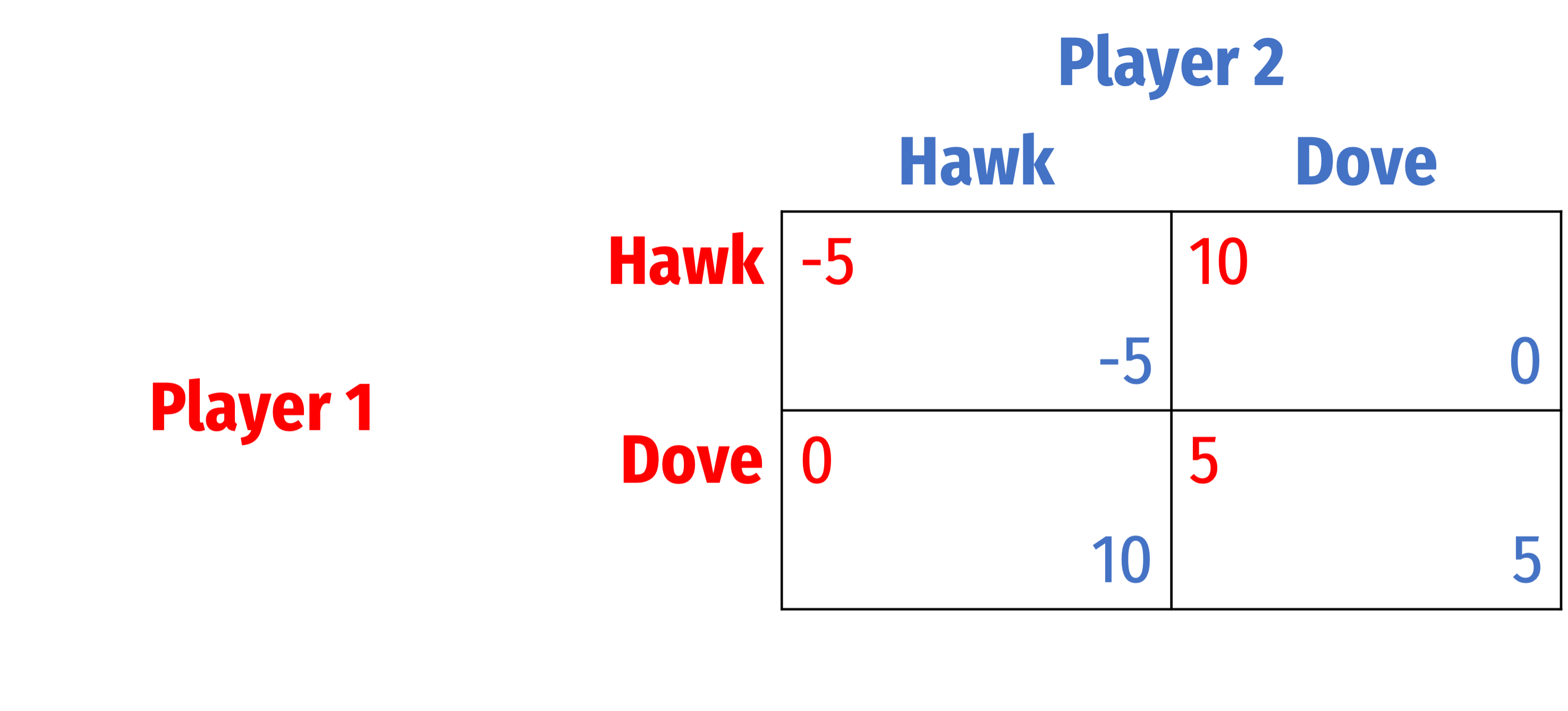

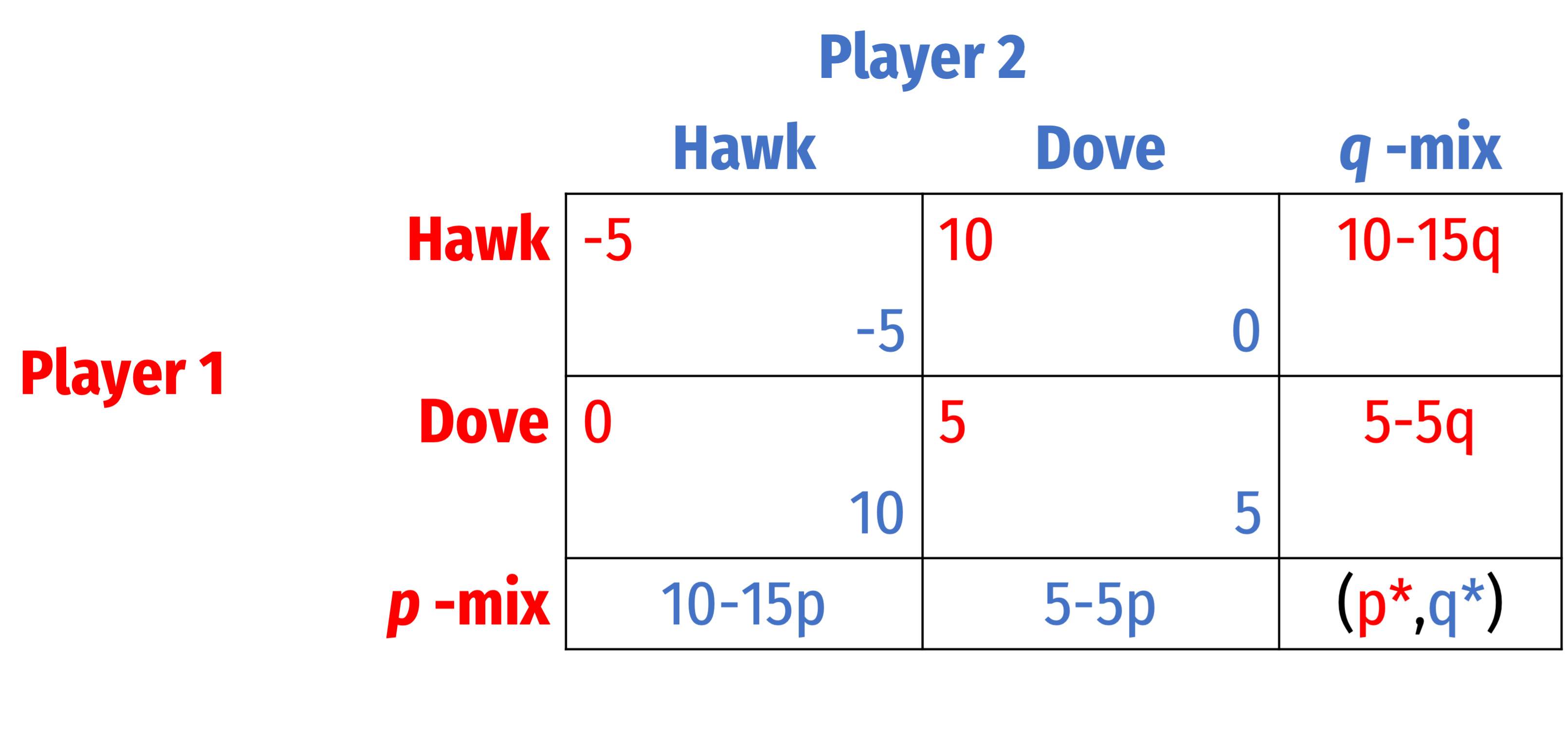

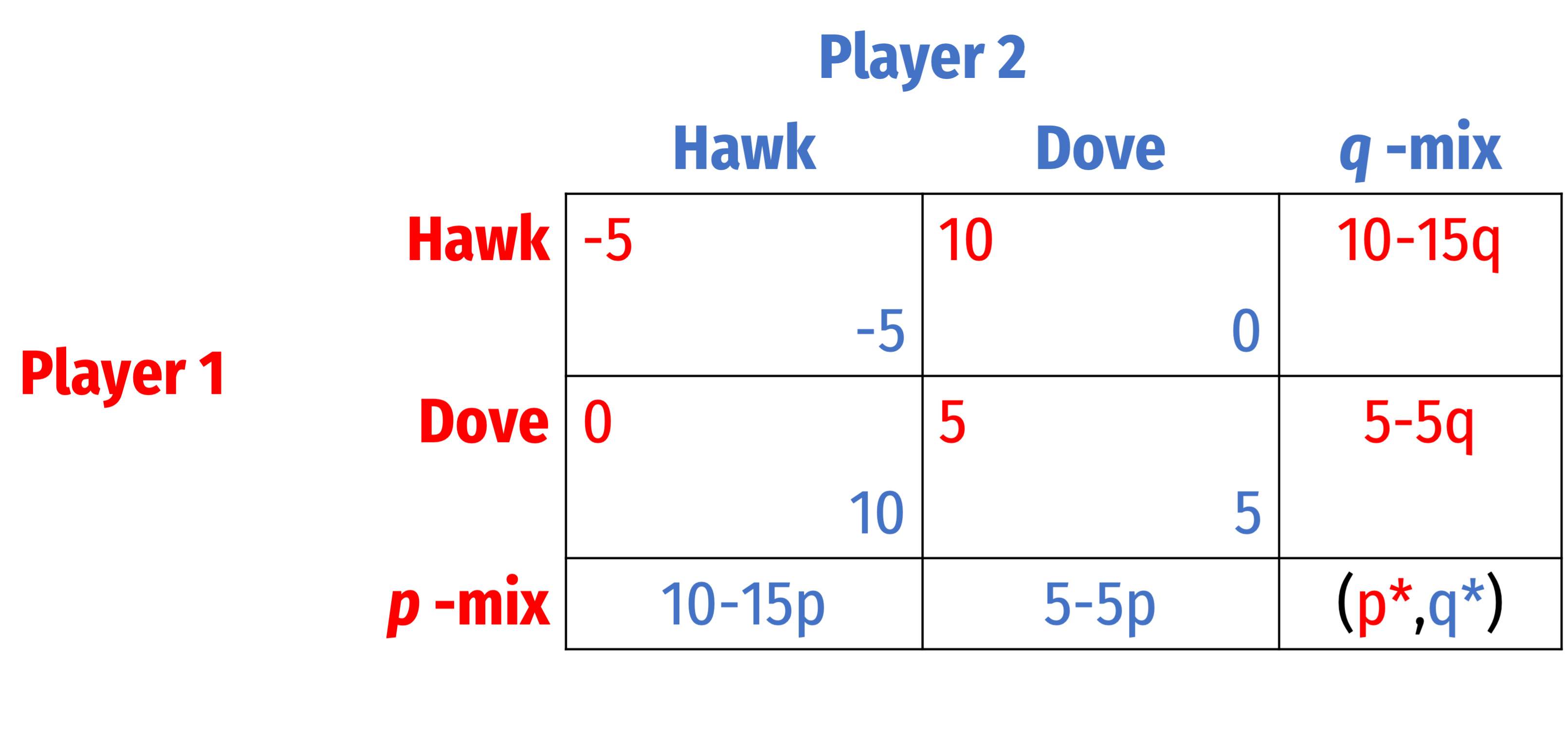

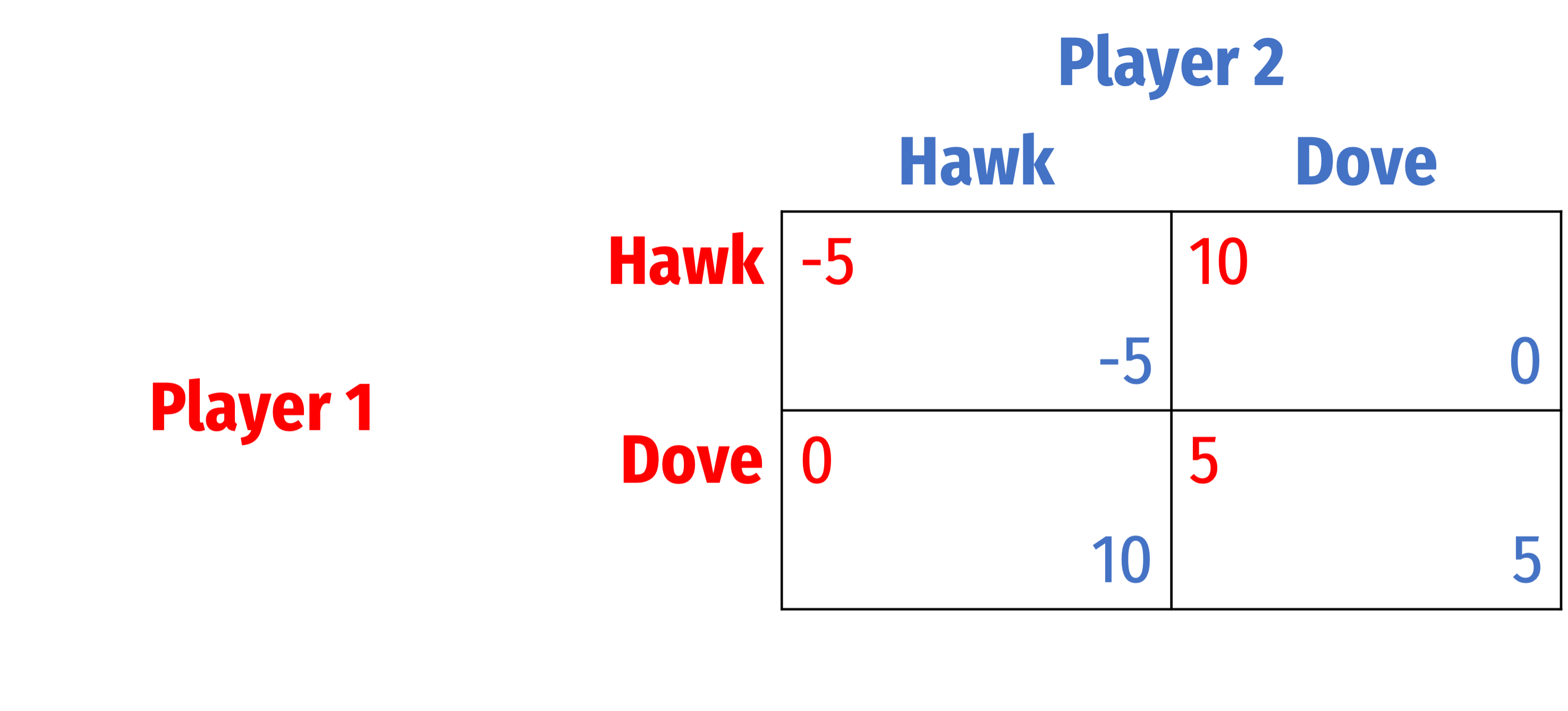

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

- If V<C, the game reduces to a game of chicken!

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

If V<C, the game reduces to a game of chicken!

Let V=10, c=20

Two PSNE: (Dove, Hawk), (Hawk, Dove)

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

If V<C, the game reduces to a game of chicken!

Let V=10, c=20

Two PSNE: (Dove, Hawk), (Hawk, Dove)

MSNE:

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

If V<C, the game reduces to a game of chicken!

Let V=10, c=20

Two PSNE: (Dove, Hawk), (Hawk, Dove)

MSNE: (p,q)=(VC,VC), in this case (0.50, 0.50)

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=−5(1−ϵ)+10(ϵ)=15ϵ−5

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=−5(1−ϵ)+10(ϵ)=15ϵ−5

Expected payoff for a mutant (Dove) type: E[Dove]=0(1−ϵ)+5(ϵ)=5ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Hawk evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Hawks who encounter a mutant Dove with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=−5(1−ϵ)+10(ϵ)=15ϵ−5

Expected payoff for a mutant (Dove) type: E[Dove]=0(1−ϵ)+5(ϵ)=5ϵ

Payoff to mutant > payoff to normal

Hawk is not ESS, will be invaded by Doves!

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Doves who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Doves who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Dove) type: E[Dove]=5(1−ϵ)+0(ϵ)=5−5ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Doves who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Dove) type: E[Dove]=5(1−ϵ)+0(ϵ)=5−5ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=10(1−ϵ)+−5(ϵ)=10−15ϵ

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

Is Dove evolutionarily stable?

Consider a population of Doves who encounter a mutant Hawk with probability ϵ

Expected payoff for a normal (Dove) type: E[Dove]=5(1−ϵ)+0(ϵ)=5−5ϵ

Expected payoff for a mutant (Hawk) type: E[Hawk]=10(1−ϵ)+−5(ϵ)=10−15ϵ

Payoff to mutant > payoff to normal

Dove is not ESS, will be invaded by Hawks!

The Hawk-Dove Game: If V<C

When V<C (Chicken), neither Hawk nor Dove is evolutionarily stable!

No monomorphic population is possible

This is because neither (Hawk, Hawk) or (Dove, Dove) are PSNE!

- Again: if strategy s is ESS, then (s,s) must be a PSNE!

There is a better response against a Hawk (or Dove) than Hawk (or Dove) itself!

- A monomorphic population of Hawks (or Doves) can always be invaded!

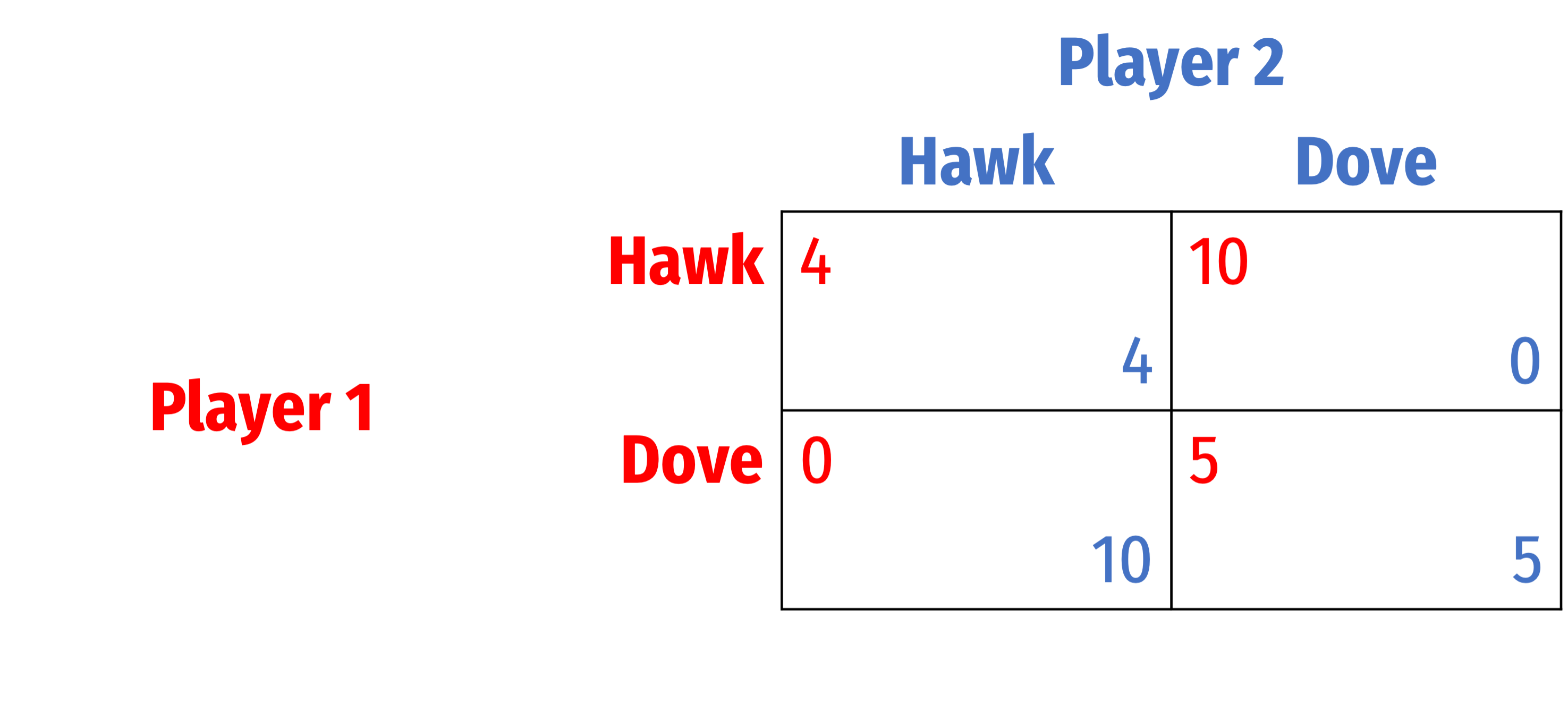

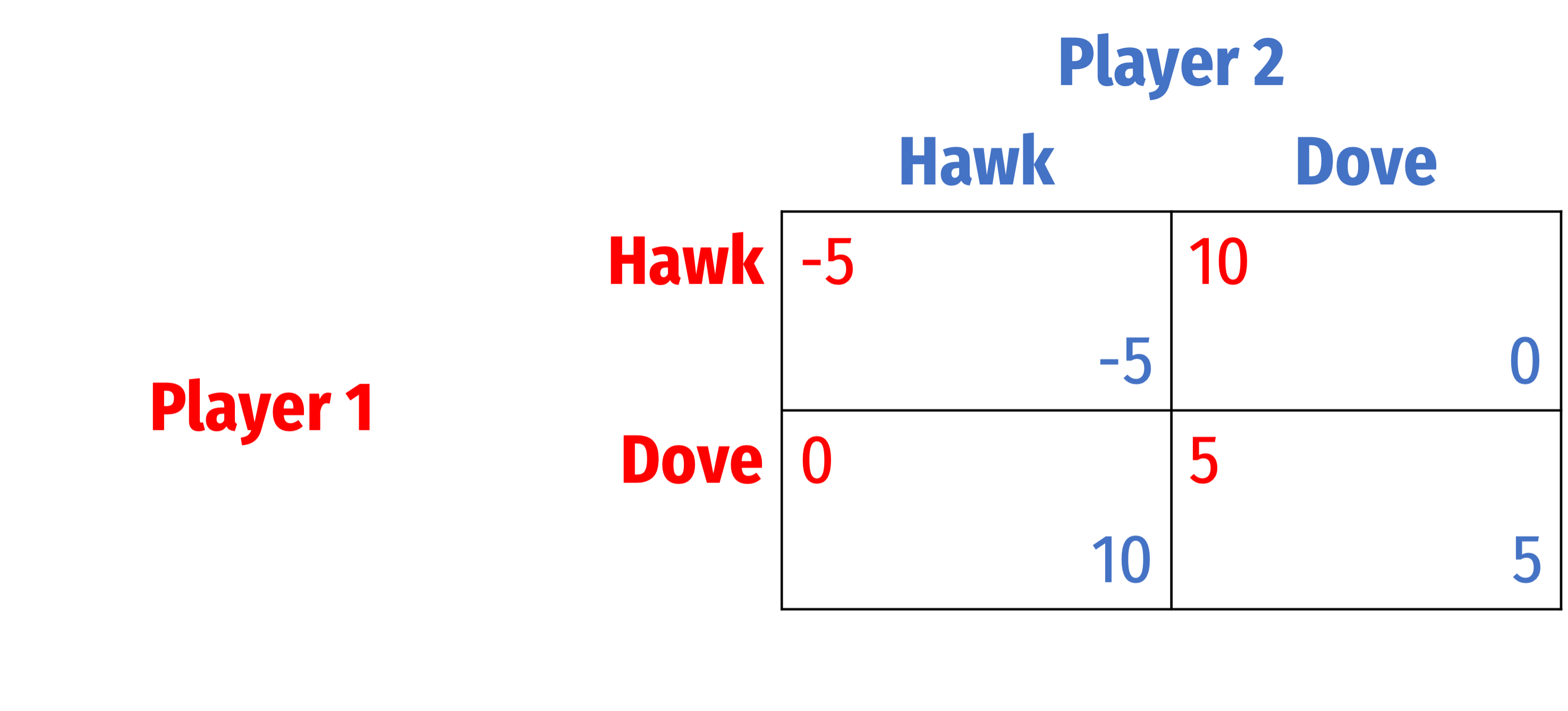

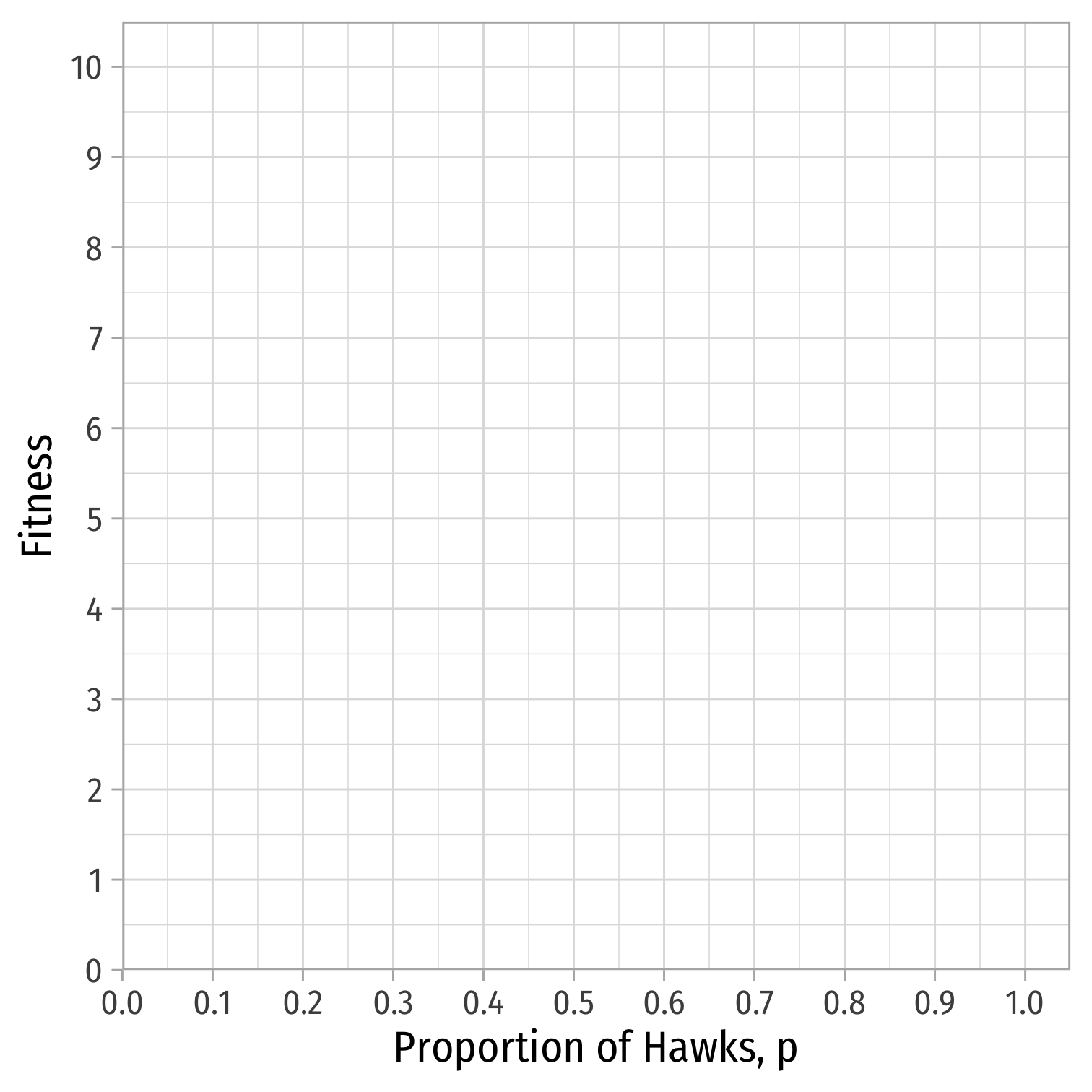

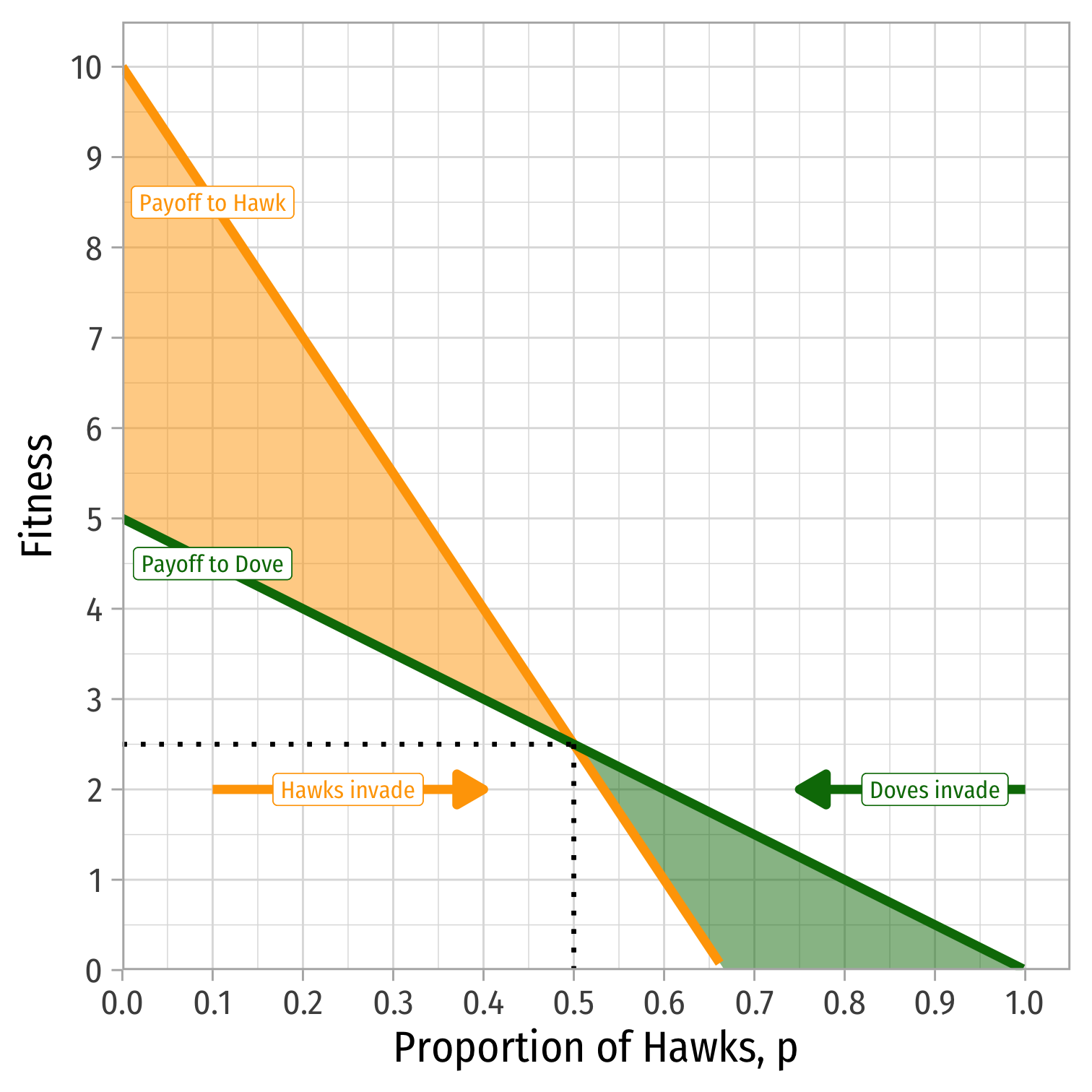

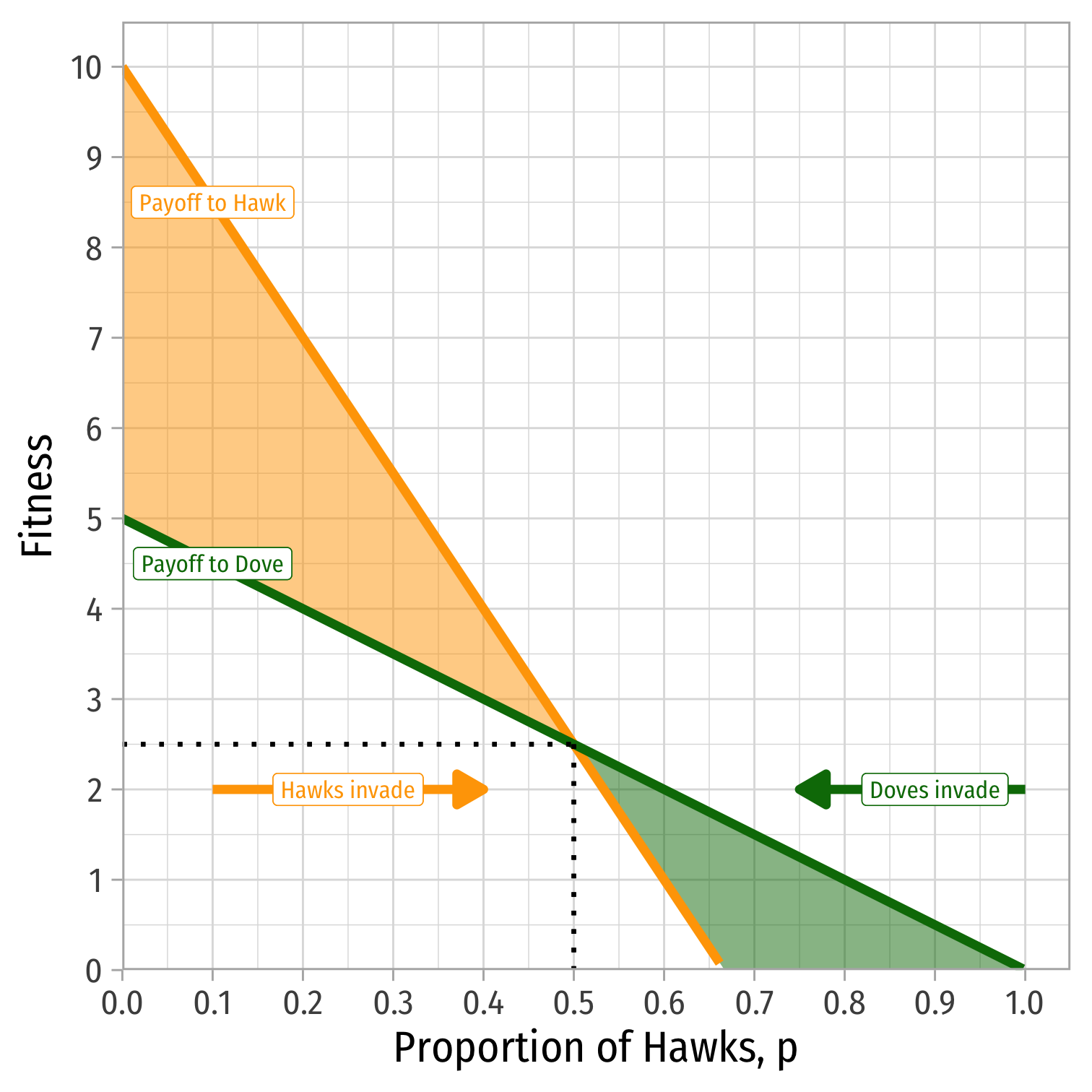

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

We must have a polymorphic population

Suppose some fraction of the population, p, are Hawks

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

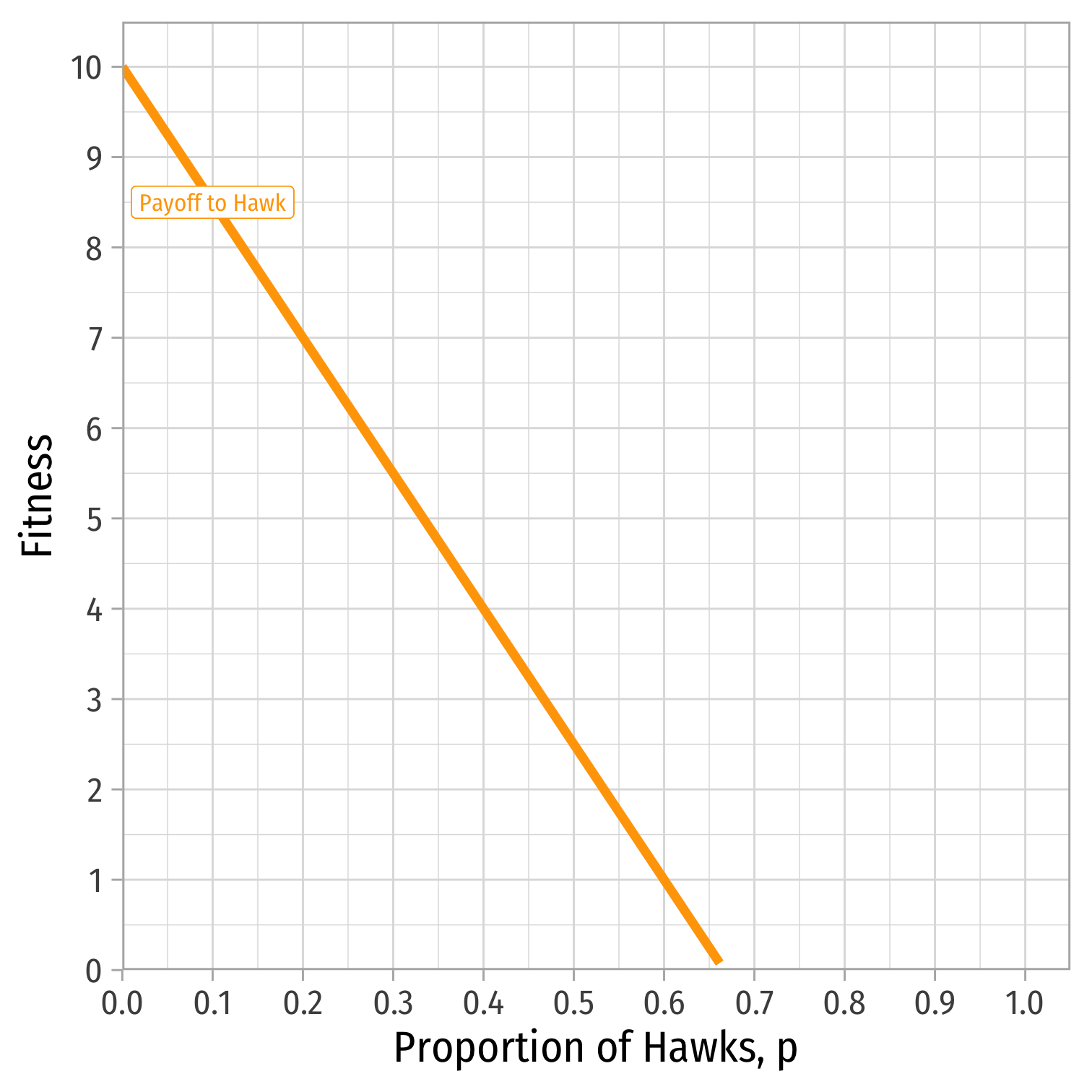

We must have a polymorphic population

Suppose some fraction of the population, p, are Hawks

- Expected payoff of a Hawk (i.e. mixed strategy)

E[Hawk]=−5p+10(1−p)=10−15p

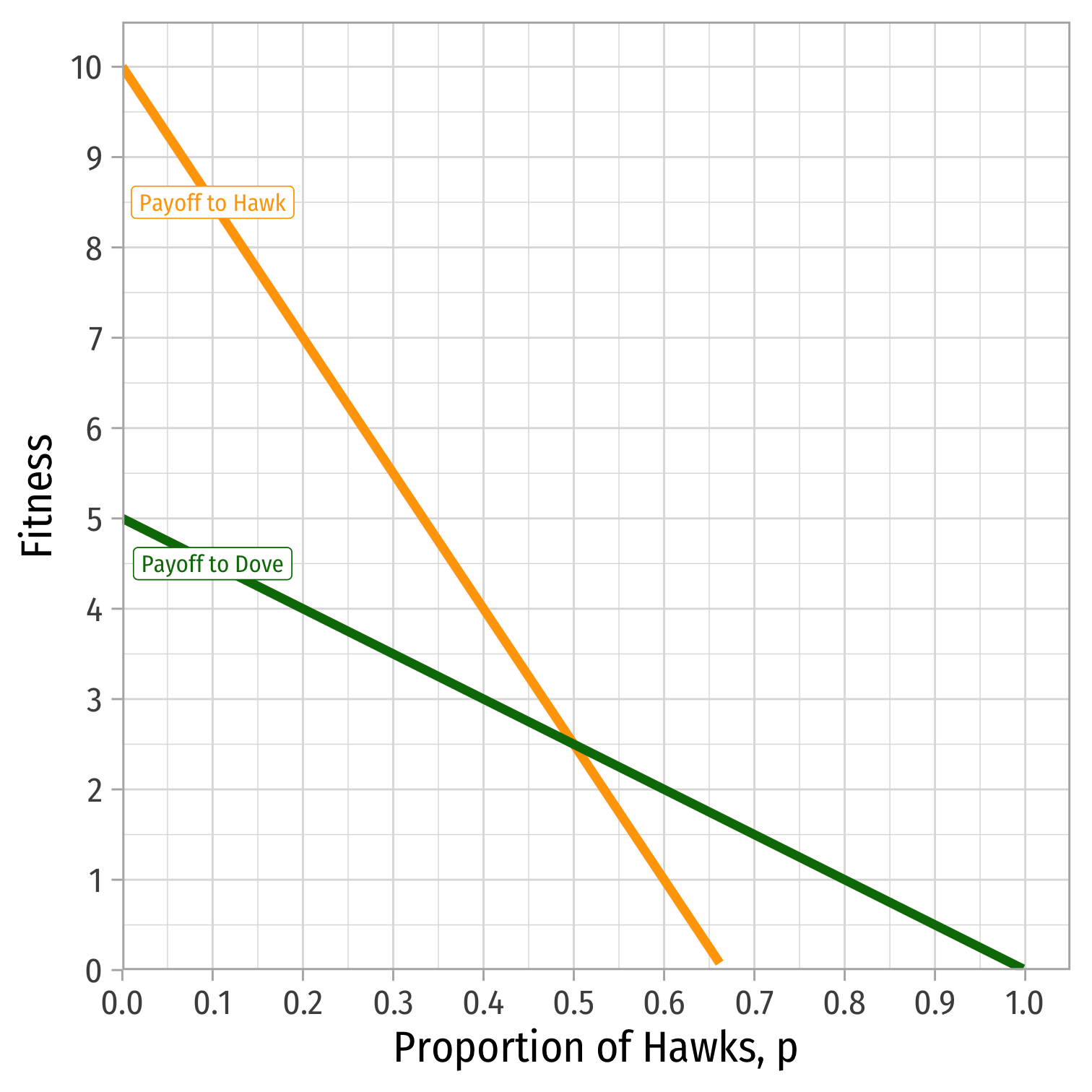

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

We must have a polymorphic population

Suppose some fraction of the population, p, are Hawks

- Expected payoff of a Hawk (i.e. mixed strategy)

E[Hawk]=−5p+10(1−p)=10−15p

- Suppose some fraction of the population, 1−p, are Doves

- Expected payoff of a Dove (i.e. mixed strategy)

E[Dove]=0p+5(1−p)=5−5p

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

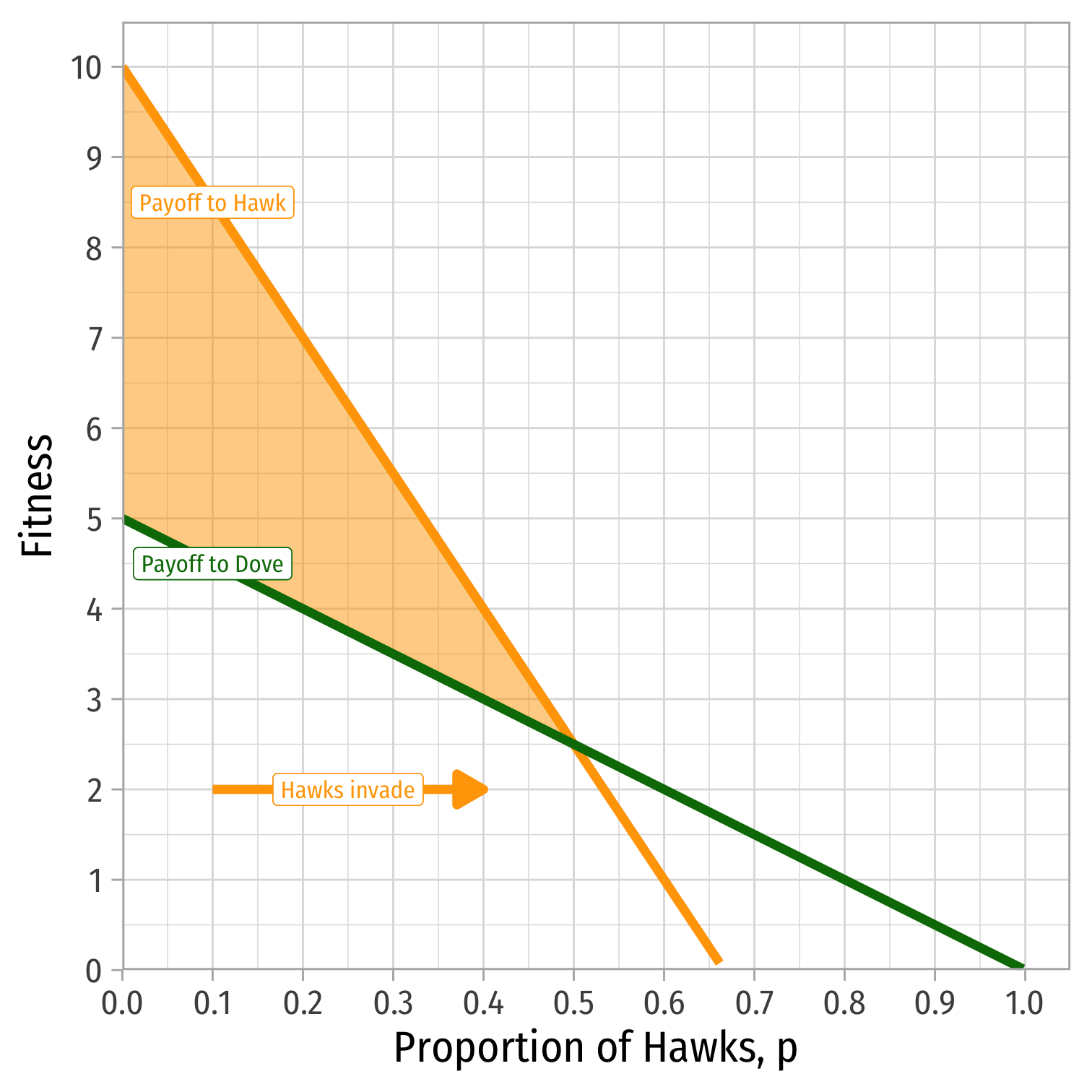

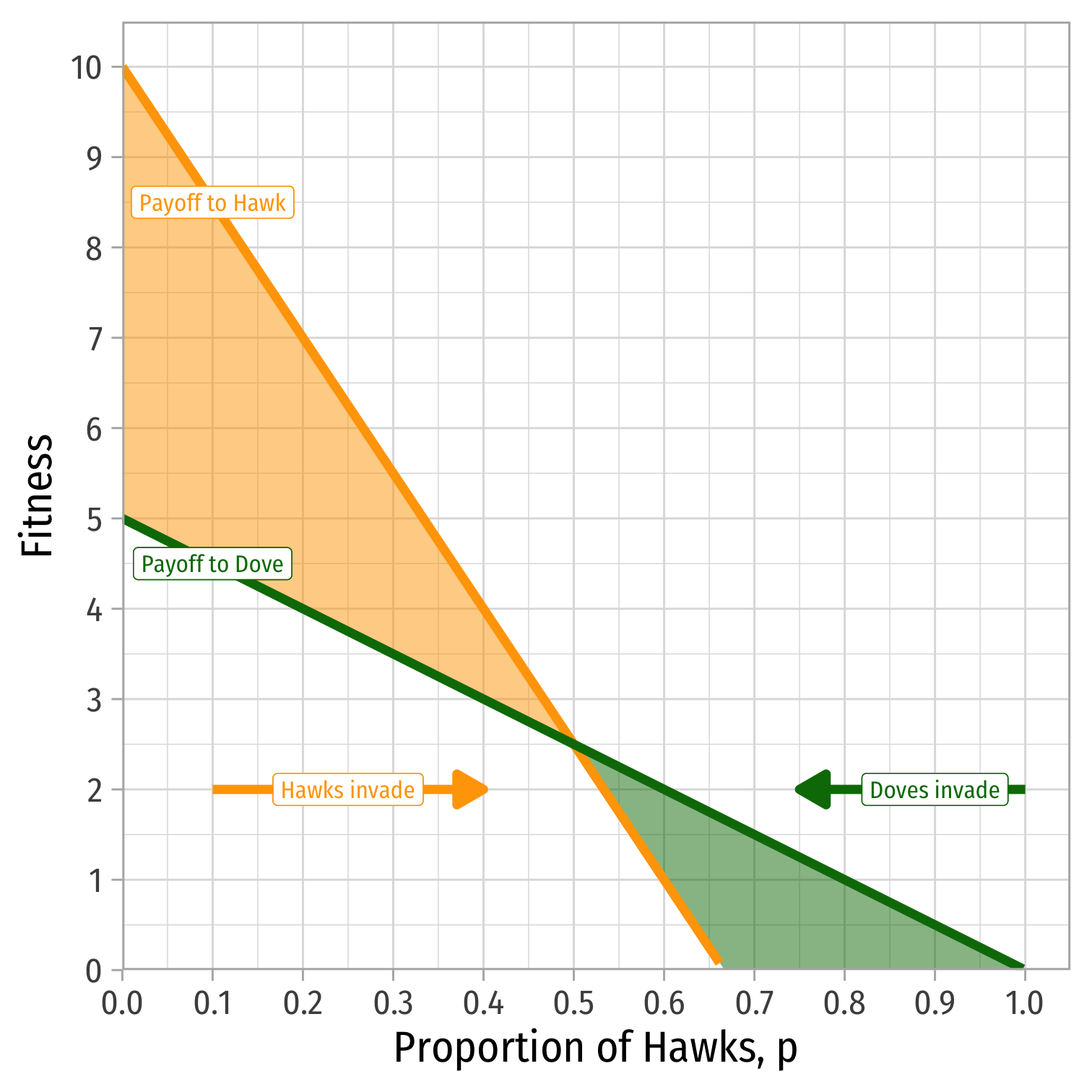

We must have a polymorphic population

If 10−15p⏟E[Hawk]>5−5p⏟E[Dove], Hawks can invade

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

We must have a polymorphic population

If 10−15p⏟E[Hawk]>5−5p⏟E[Dove], Hawks can invade

If 10−15p⏟E[Hawk]<5−5p⏟E[Dove], Doves can invade

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

We must have a polymorphic population

If 10−15p⏟E[Hawk]>5−5p⏟E[Dove], Hawks can invade

If 10−15p⏟E[Hawk]<5−5p⏟E[Dove], Doves can invade

Stable only if 10−15p⏟E[Hawk]=5−5p⏟E[Dove]

- p⋆=0.50

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

We have a polymorphic population of 50% Hawks and 50% Doves

This is the same as the MSNE with p=0.50,q=0.50

In general, p,q=Vc

- i.e. we had V=10,c=20

The Hawk-Dove Game: Polymorphic Populations

We have a polymorphic population of 50% Hawks and 50% Doves

This is the same as the MSNE with p=0.50,q=0.50

In general, p,q=Vc

- i.e. we had V=10,c=20

What about V=10,c=15?

- ESS: 23 Hawks, 13 Doves

- As ↓c or ↑V, more Hawks (better reward to fighting), and vice versa!

Polymorphic Populations and Evolutionary Instability

Hawk-dove game with V<C showed that pure strategies can be evolutionarily unstable

- A population of Hawks will be successfully invaded by mutant Doves

- A population of Doves will be successfully invaded by mutant Hawks

There is a cyclical invasion pattern with no stable equilibrium

Only stable equilibrium was a polymorphic population with a specific distribution of phenotypes

- in our earlier lingo, a mixed strategy

Polymorphic Populations and Evolutionary Instability

- Rock-paper-scissors is a great example of evolutionary instability

- A population of Rock-players will always be invaded by a Scissors-player

- A population of Scissors-players will always be invaded by a Paper-player

- A population of Paper-players will always be invaded by a Rock-player

- Only stable equilibrium is a mixed strategy (or a polymorphic population with 13 of each type)

Polymorphic Populations and Evolutionary Instability

The side-blotched lizard (Uta stansburiana) is polymorphic with three morphs, each pursuing a different mating strategy

- Orange-throated: strongest and very aggressive, don't form strong pair bonds

- Blue-throated: middle-sized, form strong pair bonds and guards female

- Yellow-throated: smallest, color mimics females (sneaks into orange's territory)

Each phenotype can successfully invade another: it's Rock-Paper-Scissors

Creates a 6-year population cycle

John Maynard Smith: “They have read my book!”

Asymmetric Games

Asymmetric Games

- Games played between different species

- Insects and plants

- Predator and prey

- Games are played by asymmetrically positioned members of same species

- Current owner of a nesting ground or food source

- Current mate vs. competitor

- Amazing thing is: many confrontations are resolved peacefully

- Current owner of food source keeps it

The Hawk-Dove Game: Bourgeois Strategy

An Owner (of territory) and an Intruder

- V≠v

- Often V>v: local knowledge, home turf advantage, sunk cost, etc

Individual organism might find itself in either role (as either player) at different times

The Hawk-Dove Game: Bourgeois Strategy

The “Bourgeois strategy” conditions behavior on the organism's role:

- Play Hawk if Owner, play Dove if Intruder

A conditional strategy (like Bourgeois) is an ESS iff it is a strict PSNE:

- (Hawk, Dove) is a PSNE when V<c and v<c

- (Dove, Hawk) a “paradoxical strategy” (but also PSNE)