3.5 — Using Game Theory in Research

ECON 316 • Game Theory • Fall 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/gameF21

gameF21.classes.ryansafner.com

Game Theory

Game theory appears somewhat tautological

- Result of game is baked into the rules of a game specified

- Game theorists often know the result even before the players play

More useful as a theoretical framework for understanding strategic interactions

- If players were rational and had perfect information — what would they do?

- Compare the (theory) prediction with reality

- Do players act differently in reality?

When Results are Not as Predicted

Behavioral economists:

- Did players make a mistake? Act less than "rational"?

- Cognitive biases, behavioral economics explanations

- Did players not understand the rules?

Game theorists:

- Did you specify the game correctly?

- Are the rules correctly modeled?

- Are the payoffs correctly specified?

Research with Game Theory

Most fruitful part of research (in my biased opinion) is using game theory to understand the role of institutions (norms, culture, shared histories, government policies, etc.)

- Coordination devices

- Focal points

- Sorting between multiple Nash equilibria

- Path dependent outcomes

- Making threats/promises credible

- Making exchanges self-enforcing

- Resolving asymmetric information problems

We'll see this starting this week, and in the papers we'll read

The Two Major Models of Economics as a “Science”

Optimization

Agents have objectives they value

Agents face constraints

Make tradeoffs to maximize objectives within constraints

The Two Major Models of Economics as a “Science”

Optimization

Agents have objectives they value

Agents face constraints

Make tradeoffs to maximize objectives within constraints

Equilibrium

Agents compete with others over scarce resources

Agents adjust behaviors based on prices

Stable outcomes when adjustments stop

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models I

Traditional economic models are often called “Decision theory”:

Optimization models ignore all other agents and just focus on how can you maximize your objective within your constraints

- Consumers max utility; firms max profit, etc.

Outcome: optimum: decision where you have no better alternatives

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models I

Traditional economic models are often called “Decision theory”:

Equilibrium models assume that there are so many agents that no agent’s decision can affect the outcome

- Firms are price-takers or the only buyer or seller

- Ignores all other agents’ decisions!

Outcome: equilibrium: where nobody has any better alternative

Game Theory vs. Decision Theory Models III

Game theory models directly confront strategic interactions between players

- How each player would optimally respond to a strategy chosen by other player(s)

- Lead to a stable outcome where everyone has considered and chosen mutual best responses

Outcome: Nash equilibrium: where nobody has a better strategy given the strategies everyone else is playing

Equilibrium in Games

- Nash Equilibrium:

- no player wants to change their strategy given all other players’ strategies

- each player is playing a best response against other players’ strategies

A Suggested Framework

I. Identify the strategic interaction

- Who are the players

- What choices can they make?

- How does the interaction of their choices determine outcomes for each player?

A Suggested Framework

II. Model the game: rules, payoffs, etc (often the hard part!)

- Ordering of choices -- sequential, simultaneous?

- Information -- what does each player know and not know

- One-shot or repeated?

- If repeated: a finite number of times? an infinite number of times? ending with certain probability?

- Define the payoffs (again, the hard part!)

- use economic theory to determine how various interactions should affect various outcomes for each player

- numerical payoffs make things easy, but constrain you to fewer possibilities

- using variables in payoffs allows you to solve for the conditions that will yield different Nash equilibria

A Suggested Framework

III. Predict the outcome(s)

- Solve for Nash equilibria

- If applicable, consider: pure vs. mixed strategies, one-shot vs. repeated games

- If using variables in payoffs, what values of variables will give us various equilibria?

- If multiple equilibria -- any reasons we should expect one over others?

A Suggested Framework

IV. Compare reality with predictions

- Are there behavioral reasons players do not reach predicted outcome?

- Are there institutions, policies, norms, ethics, etc. that lead players towards/away from certain outcomes?

V. Consider changes in the game

- What would have to change (payoffs, rules, etc) to get different outcomes?

- Are there policies or institutions that might affect or cause this?

- Consider welfare of players: how do the players do? How could this be improved?

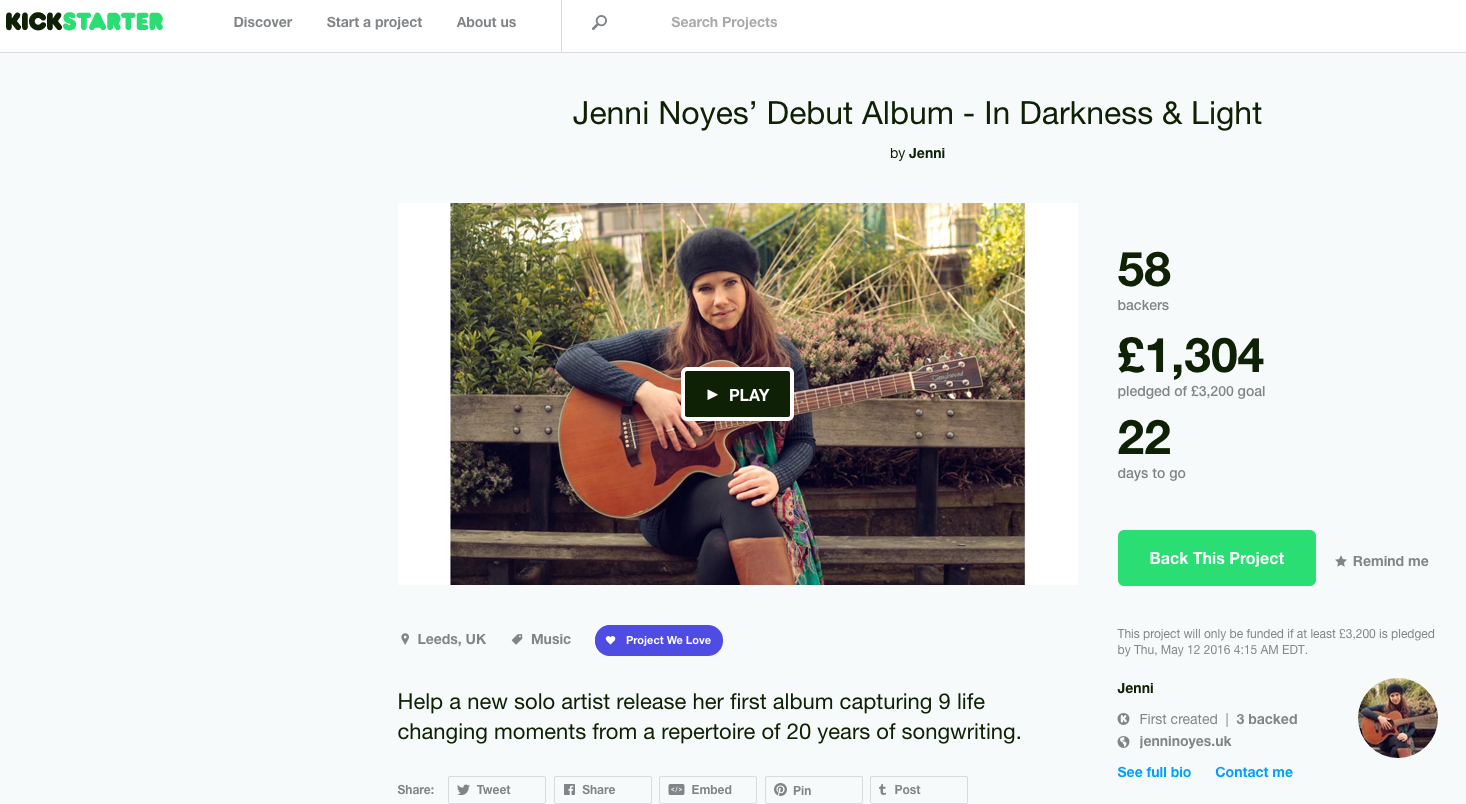

Example I: Patronage, Copyright, and Crowdfunding as Alternative Institutions

Patronage

Patronage Today

Patronage Today

Patronage Today

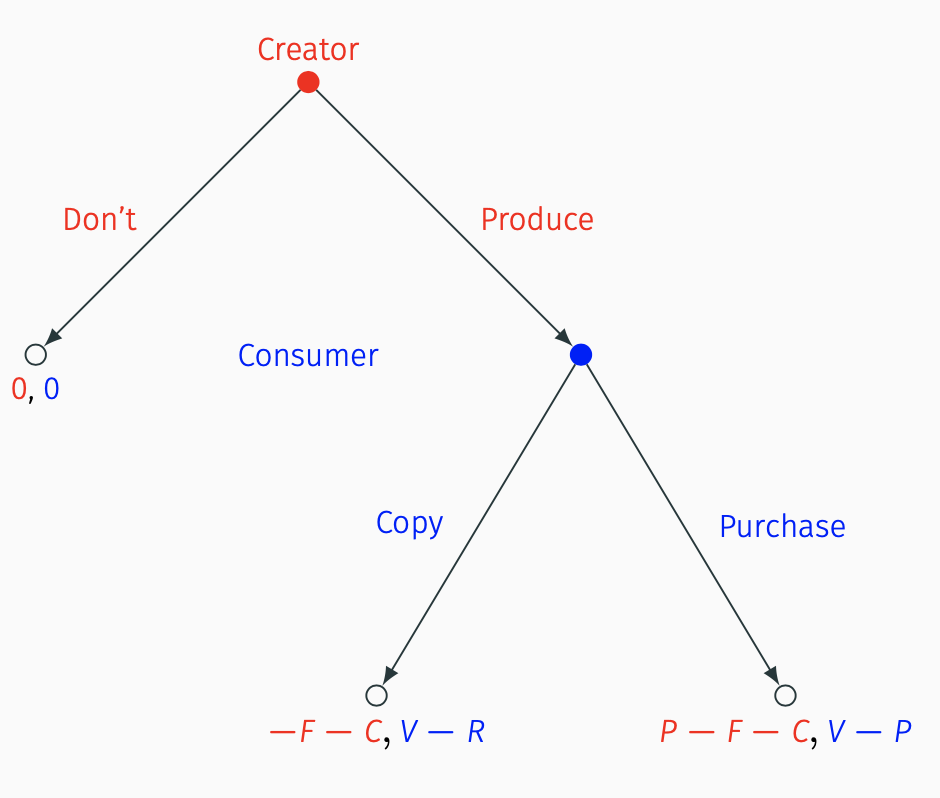

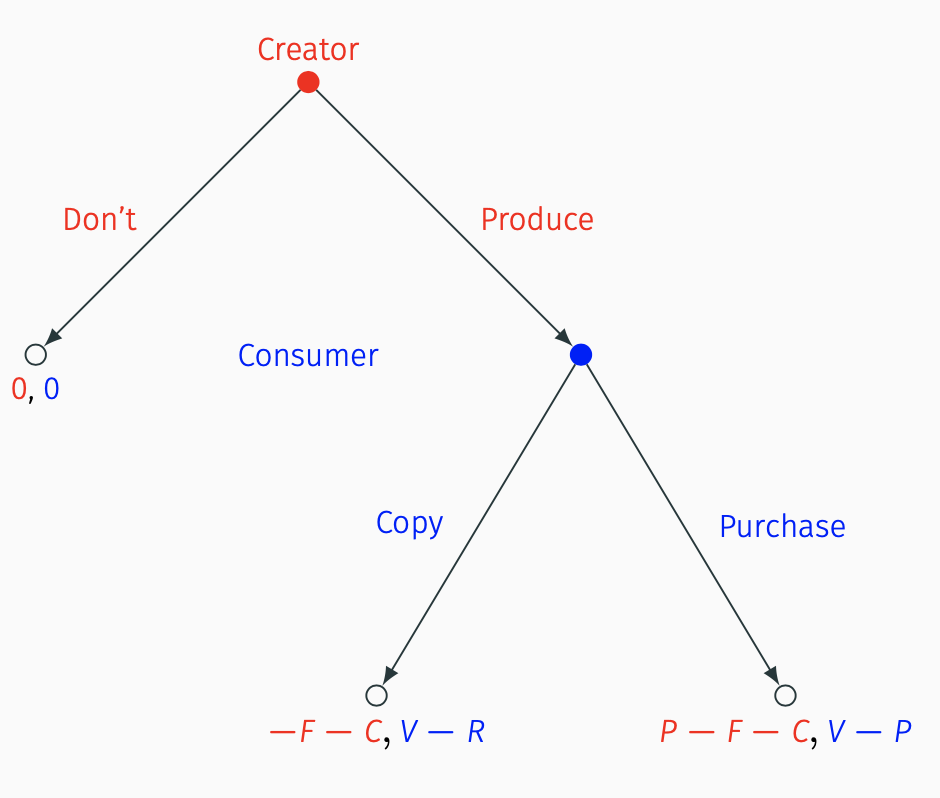

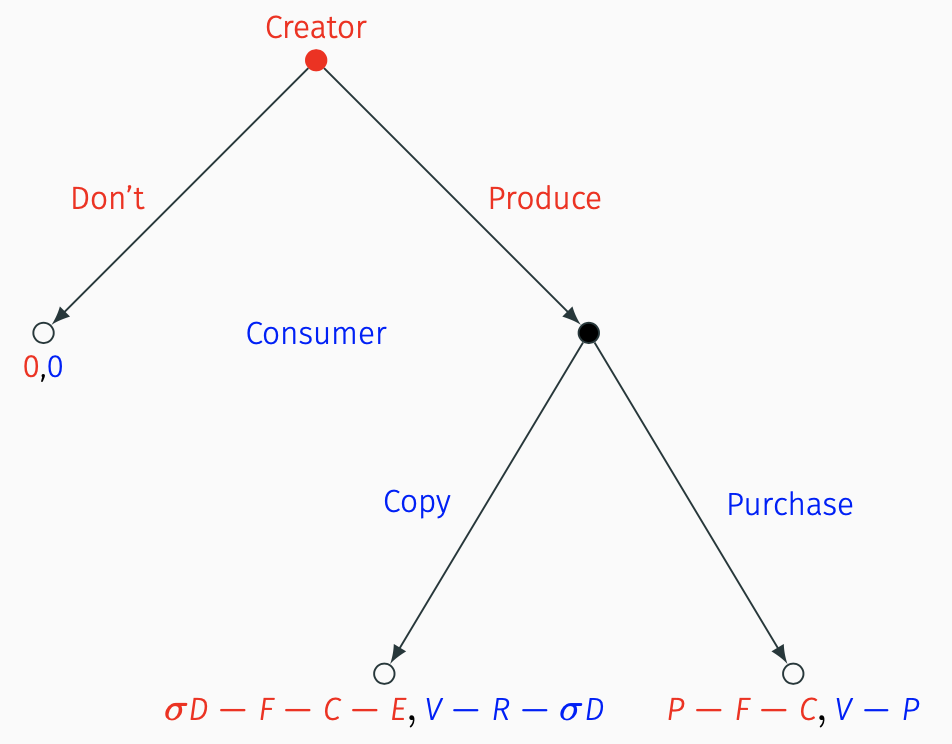

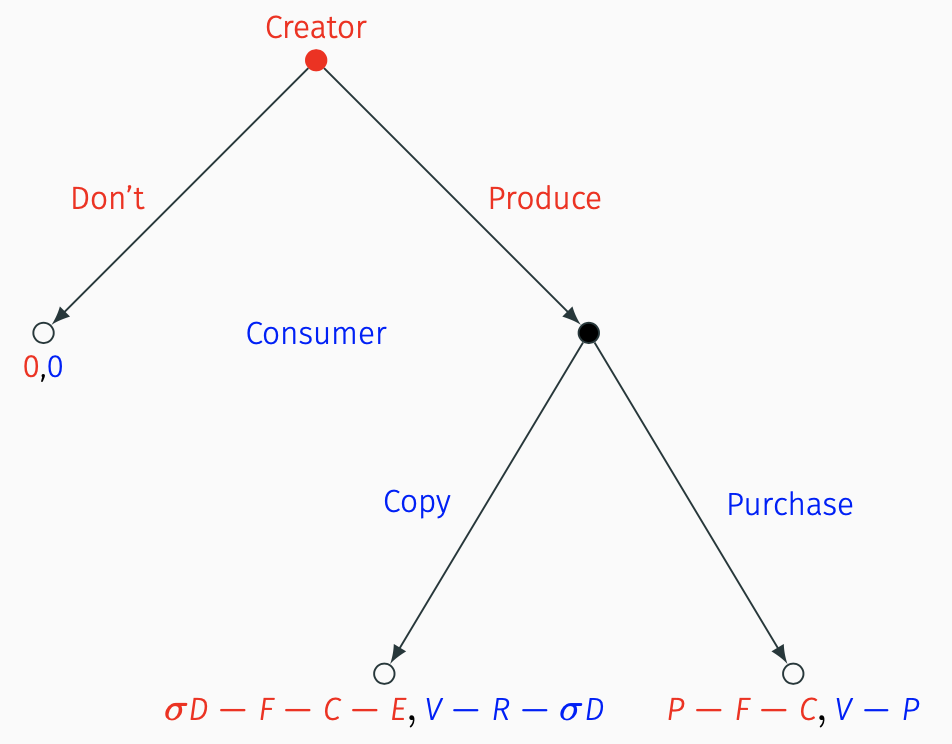

Basic Game

Creator can produce a (single) expressive work

- Fixed cost \(F\)

- Marginal cost \(C\)

- If produced, incur cost \(-(F+C)\), and sell at price \(P\)

Consumer can consume or copy expressive work

- Values it at \(V\)

- Purchases at price \(P\)

- \(V-P\): consumer surplus

- Copies with replication cost, \(R\)

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Kickstart My Art: Are Crowdfunding and Intellectual Property Complements or Substitutes?”

Basic Game

Solve this game by backwards induction:

Consumer will Purchase when:

- \(R>P\): costlier to copy than to purchase

- \(V>P\): price to buy is lower than value (i.e. consumer surplus, \(V-P \geq 0\))

Producer will Produce when:

- Consumer Purchases

- \(P>F-C\): revenue exceeds cost

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Kickstart My Art: Are Crowdfunding and Intellectual Property Complements or Substitutes?”

Mechanisms to Enhance Cooperation

- An agent ("patron") bears the fixed costs (F) in exchange for some of the following:

- Distribution rights (copyrights); personal prestige; portion of profits; rewards

- Deterrence of pirating & shirking (raise R relative to P)

- Technology affects replication costs; Customization, product differentiation, price discrimination; Legal threats; Reputation

- Compare three systems:

- Patronage of the arts

- Copyright

- Crowdfunding

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Kickstart My Art: Are Crowdfunding and Intellectual Property Complements or Substitutes?”

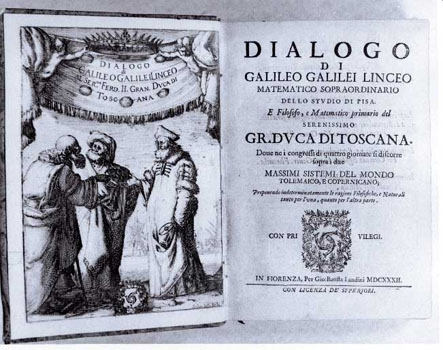

Patronage of the Arts (& Sciences)

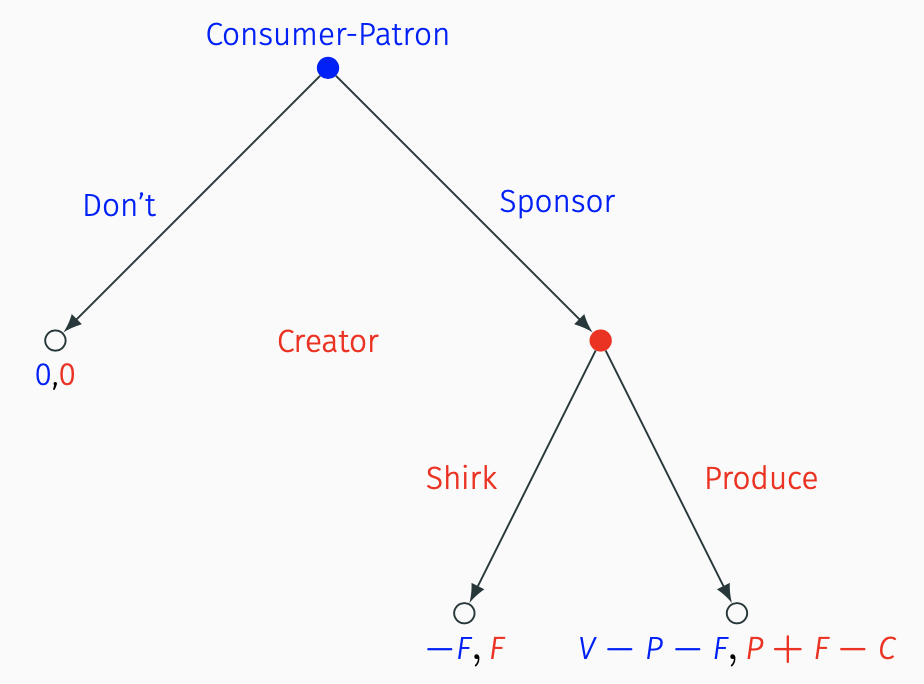

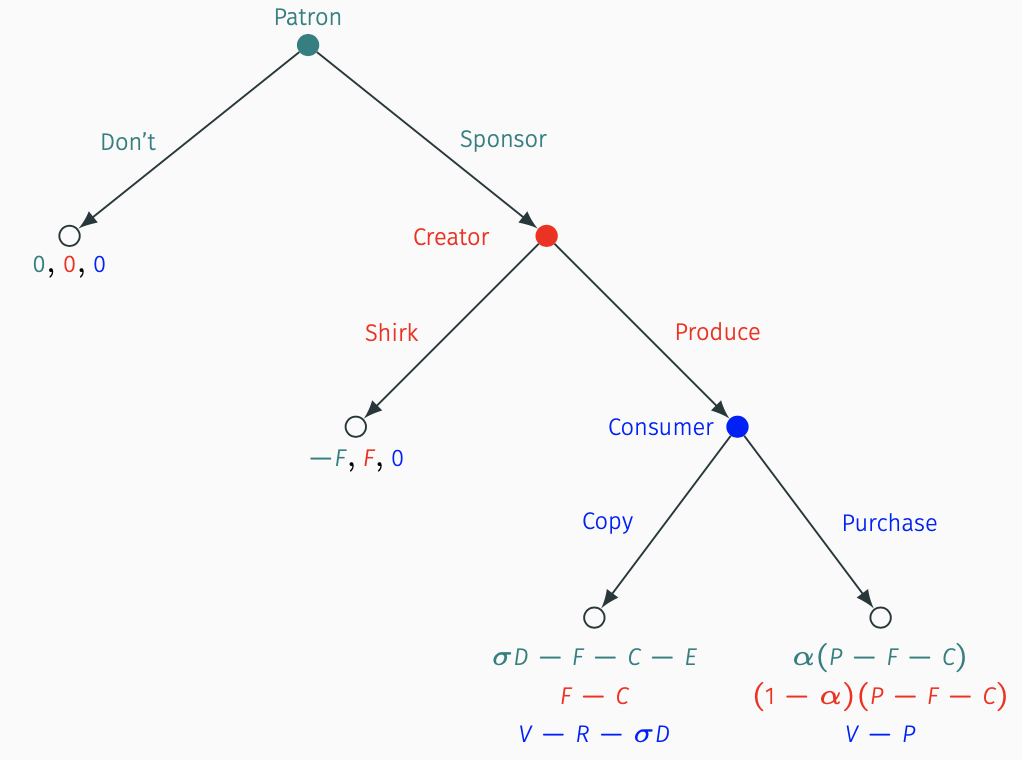

Patronage Version of the Game

Patronage of the arts: institution that changes the rules of the game

- Consumer-Patron decides to sponsor a Creator by bearing their fixed costs F

- Creator now in a principal-agent problem: produce or shirk (abscond with F)

Rules of the game that affect key parameters:

- Removes opportunity of copying (custom works)

- F: fixed costs now borne by patron

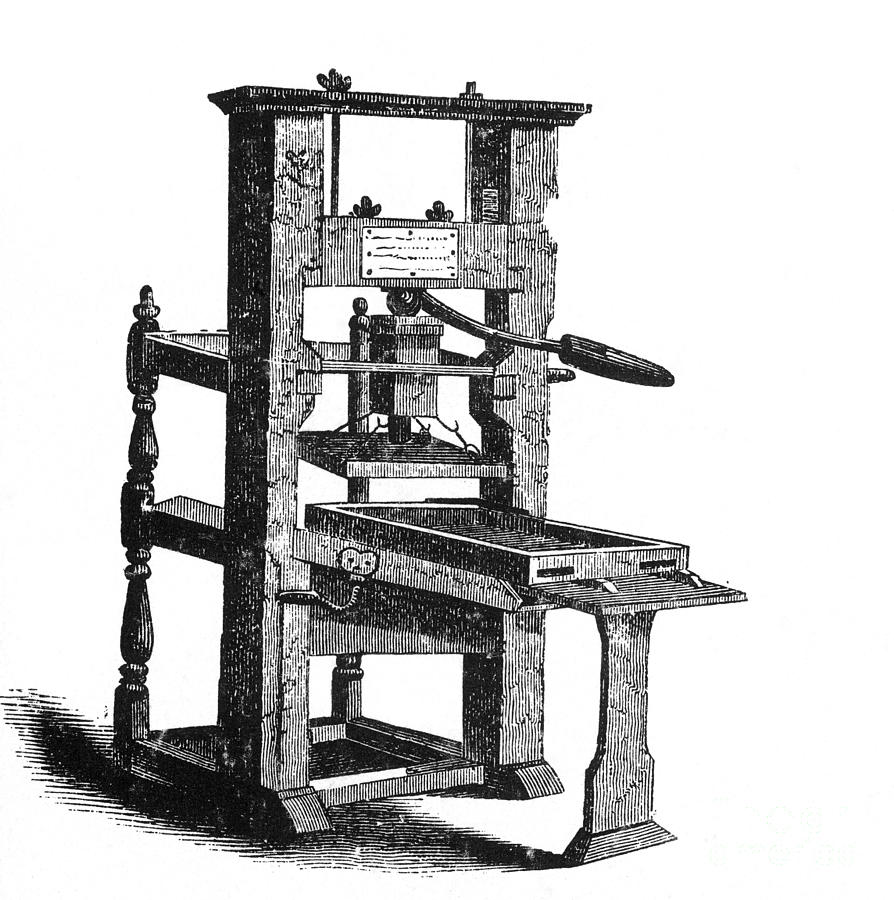

Copyright

Cost of replication has plummeted via new technology (both for creators & for copyists)

Copyright: Individual creator can control distribution rights and seek legal sanctions against copyists

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Kickstart My Art: Are Crowdfunding and Intellectual Property Complements or Substitutes?”

Copyright Version of the Game

- Copyright: another institution that changes the payoffs of the original game

- If Consumer chooses to Copy, now faces additional:

- \(D\): damages from copyright lawsuit

- \(\sigma\): probability of getting caught/sued

- Creator gains \(\sigma D\) (from lawsuit against Consumer), but must pay \(E\) for enforcement costs (legal fees)

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Kickstart My Art: Are Crowdfunding and Intellectual Property Complements or Substitutes?”

Copyright Version of the Game

- Consumer purchases when:

- \(P<R-\sigma D\)

- More likely than first version of game

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Kickstart My Art: Are Crowdfunding and Intellectual Property Complements or Substitutes?”

Patronage with Copyright/Crowdfunding Version

Patronage with Copyright: three players

- patron and consumer are different

- patron can sponsor creator by bearing \(F\)

- patron contracts for copyright and some share \(\alpha\) of the profits

Crowdfunding: patrons \(\neq\) wealthy elites, but a collection of many people contributing towards \(F\)

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Kickstart My Art: Are Crowdfunding and Intellectual Property Complements or Substitutes?”

Example II: 19th Century American Literary Piracy

From 18th—mid 20th century the United States refused to respect copyright of foreign authors

American publishing industry expressly built on piracy of foreign works (mostly British novels)

The U.S. is now the world's copyright policeman, enforcing its copyrights internationally

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Honor Among Thieves: How 19th Century American Pirate Publishers Simulated Copyright Protection”

Example II: 19th Century American Literary Piracy

U.S. publishers' piracy of foreign authors in the 19th century faced a tragedy of the commons:

- No exclusive claims over printing foreign works (no copyright \(\implies\) no right to exclude)

Solved this problem by creating a publishing cartel that created "property rights" in piracy of foreign authors

Enabled protectionist resistance to calls for respecting international copyrights

- System broke down by end of 19th century

- Rising U.S. cultural output in 20th century: publishers now advocate for international copyrights

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Honor Among Thieves: How 19th Century American Pirate Publishers Simulated Copyright Protection”

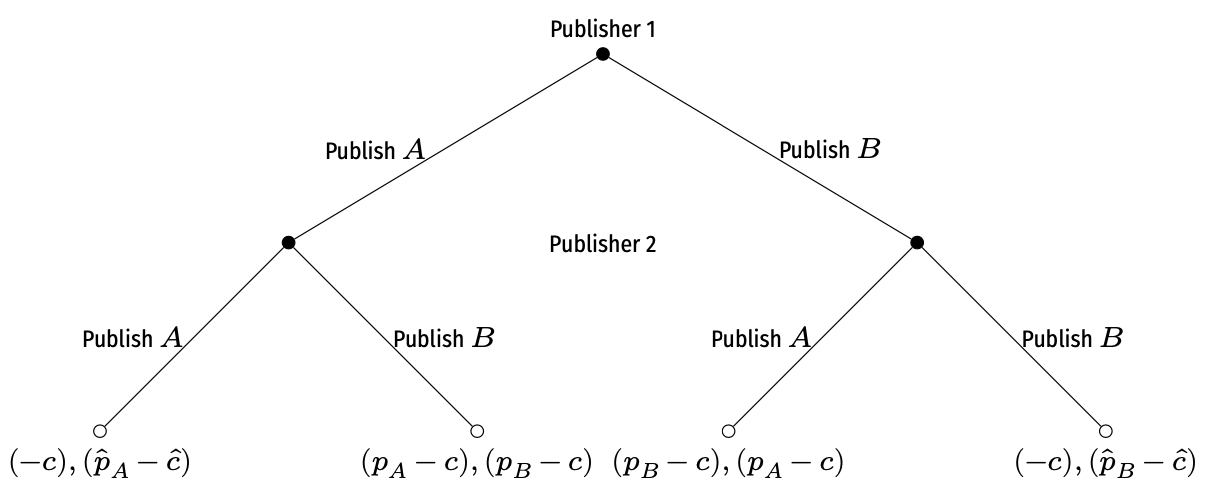

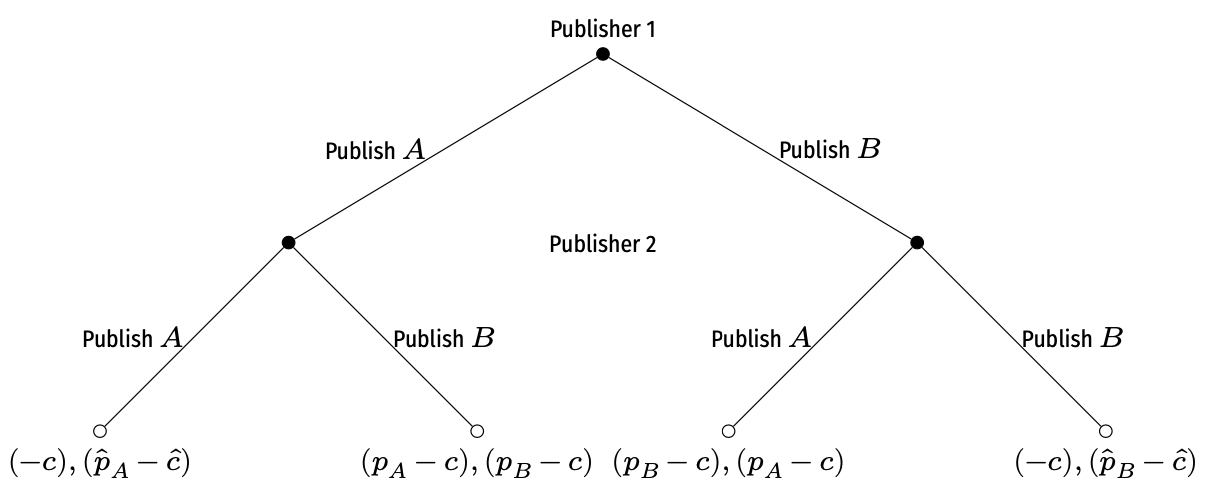

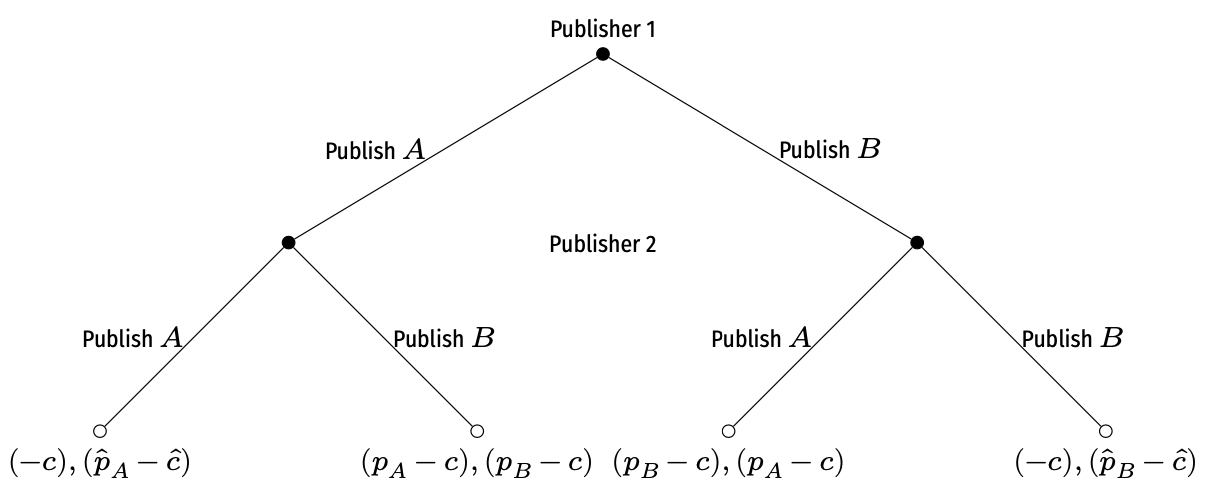

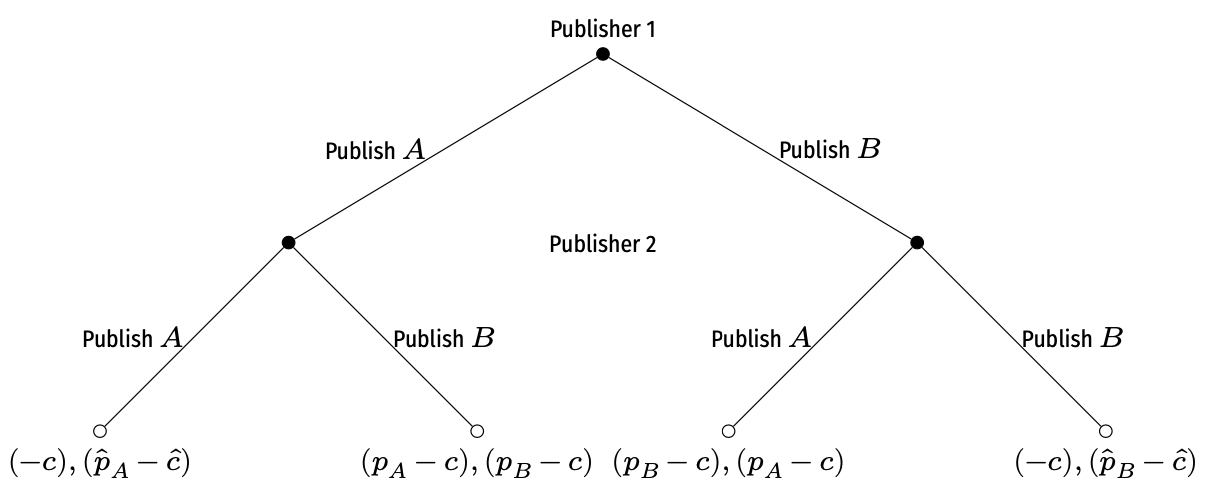

Game Setup

Two representative American publishers, 1 and 2; two authors \(A\), and \(B\)

Publisher 1 moves first and decides to publish \(A\) or \(B\) at profit-maximizing price \(p\) with cost \(c\)

Publisher 2 moves second and can decide to publish:

- the same author as 1 ("pirate") at lower cost \(\hat{p}<p; \hat{c}<c\) or

- the other author at cost \(c\)

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

Game Setup

- Consumers will buy only from lower-priced publisher

- If publisher 2 pirates, can sell at lower price than publisher 1

- If both publish different authors, each earns \(p_i-c\), where \(i=\{A, B\}\)

- Authors \(A\) and \(B\) may fetch different prices \(p_A\) and \(p_B\) depending on market demand

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

Game Setup

- Piracy/original publishing depends on:

- relative value of author \(A\) vs \(B\)

- profits of original sales \((p_i-c)\) vs. profits of pirate sales \((\hat{p_i}-\hat{c})\)

- both demand for pirated works \((\hat{p_i})\) and reproduction technology \((\hat{c})\)

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

Game Outcome - Role of Institutions

Parameters \(p_A\), \(p_B\), \(c\), and \(\hat{c}\) are determined by market conditions and institutions:

Historically, several methods to secure property rights and deter piracy from other publishers

- Arts patronage

- Monopoly/guild (Stationers' Company of London)

- Internal trade organizations

- Copyright law

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

The Cartel Solution: “Courtesy of the Trade”

1790—1891 U.S. did not recognize copyrights to foreign authors

U.S. publishing industry largely pirated famous British authors

- Set up “courtesy of the trade” system of voluntary norms to avoid tragedy of commons

- Created pseudo-property rights in foreign authors works

- Ended up paying authors despite no obligation to, nor any legal protection earned

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Honor Among Thieves: How 19th Century American Pirate Publishers Simulated Copyright Protection”

The Cartel Solution: “Courtesy of the Trade”

1790—1891 U.S. did not recognize copyrights to foreign authors

Resolved the tragedy of the commons problem via a cartel

- A publisher would announce which foreign author they would publish and stake their "claim"

- Other publishers would refrain from republishing that author, in hopes that when they stake a claim on a different author, others would respect it

- If didn't respect claims, retaliation: nobody would respect their future claims

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Honor Among Thieves: How 19th Century American Pirate Publishers Simulated Copyright Protection”

More General Solutions

1891 International Copyright Act “respects” foreign copyrights in U.S.

- “Manufacturing clause” required foreign works to be printed in U.S.

- Rationale for “trade courtesy” cartel disappears

U.S. publishers begin publishing U.S. authors

- Now in their interest to push for other countries to respect U.S. copyright

Safner, Ryan, 2021, “Pirate Thy Neighbor: The Protectionist Roots of International Copyright Recognition in the United States”