4.2 — Credible Commitments

ECON 316 • Game Theory • Fall 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/gameF21

gameF21.classes.ryansafner.com

Credible Commitments

Another Motivating Example: Why Professors Are Mean

Most professors have a lateness policy where late homework is either not accepted, or points are lost

Not (necessarily) because professors are mean!

Suppose a student hands in homework late and has a plausible excuse

Most professors actually are generous and accommodating, will make an exception

But if students know this, all students will try plausible excuses and everything becomes late

Another Motivating Example: Why Professors Are Mean

Professor can commit to a bright-line policy from the beginning (i.e. in syllabus)

Removes professor's discretion in individual cases

The policy may be "mean", but leads to a better Nash equilibrium by tying professor's hands

Salespeople have same limitations from "manager" or "man upstairs" preventing better deals

What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Stronger

Committing to something is costly in the short-run, but often makes the commit-er better off in the long run

Often need some kind of commitment device to artificially constrain your ability to react

What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Stronger

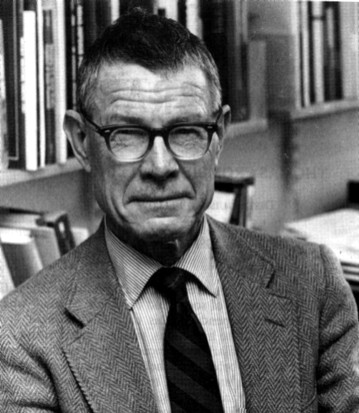

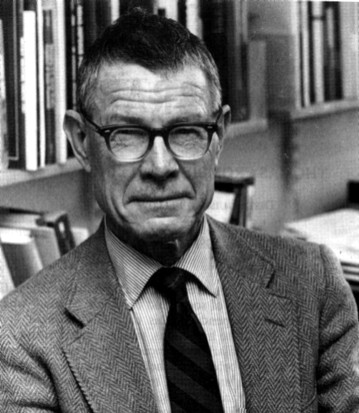

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“Bargaining power"..s that the advantage goes to the powerful, the strong, or the skillful. It does, of course, if those qualities are defined to mean only that negotiations are won by those who win...The sophisticated negotiator may find it difficult to seem as obstinate as a truly obstinate man,” (p.22).

“Bargaining power [is] the power to bind oneself,” (p.22).

What Doesn't Kill You Makes You Stronger

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“How can one commit himself in advance to an act that he would in fact prefer not to carry out in the event, in order that his commitment may deter the other party? ... In bargaining, the commitment is a device to leave the last clear chance to decide the outcome with the other party, in a manner that he fully appreciates; it is to relinquish further initative, having rigged the incentives so that the other party must choose in one's favor. If one driver speeds up so that he cannot stop, and the other realizes it, the latter has to yield...This doctrine helps to understand some of those cases in which bargaining 'strength' inheres in what is weakness by other standards.,” (p.22).

Why Are the Following So Difficult?

New Years Resolutions

Waking up early

Dieting

Going to the gym

Time-inconsistency Problem

- Time inconsistency problem: Future you will have different preferences at the moment of truth than Present you has now

Time Inconsistency and Commitment Devices

With a commitment device you can bind yourself in the future to obey your present wishes

Limiting your future choices keeps your preferences consistent over time

Examples:

- Deadlines

- Rely on other people

- Stake your reputation on it

- Impose a high cost on yourself for failure

- Hire an agent who is compensated based on your success

Ways to Commit and Make Strategies Credible

- Dixit and Nalebuff (Ch. 7) describe 8 methods to make strategies credible (and also suggestions for countering them):

- Write enforceable contracts

- Establish and stake your reputation on your actions

- Cut off communication

- Burn bridges behind you

- Leave the outcome beyond your control, or to chance

- Move in small steps

- Develop credibility through teamwork

- Employ mandated agents

Write Contracts

Write Contracts

Cut Off Communication

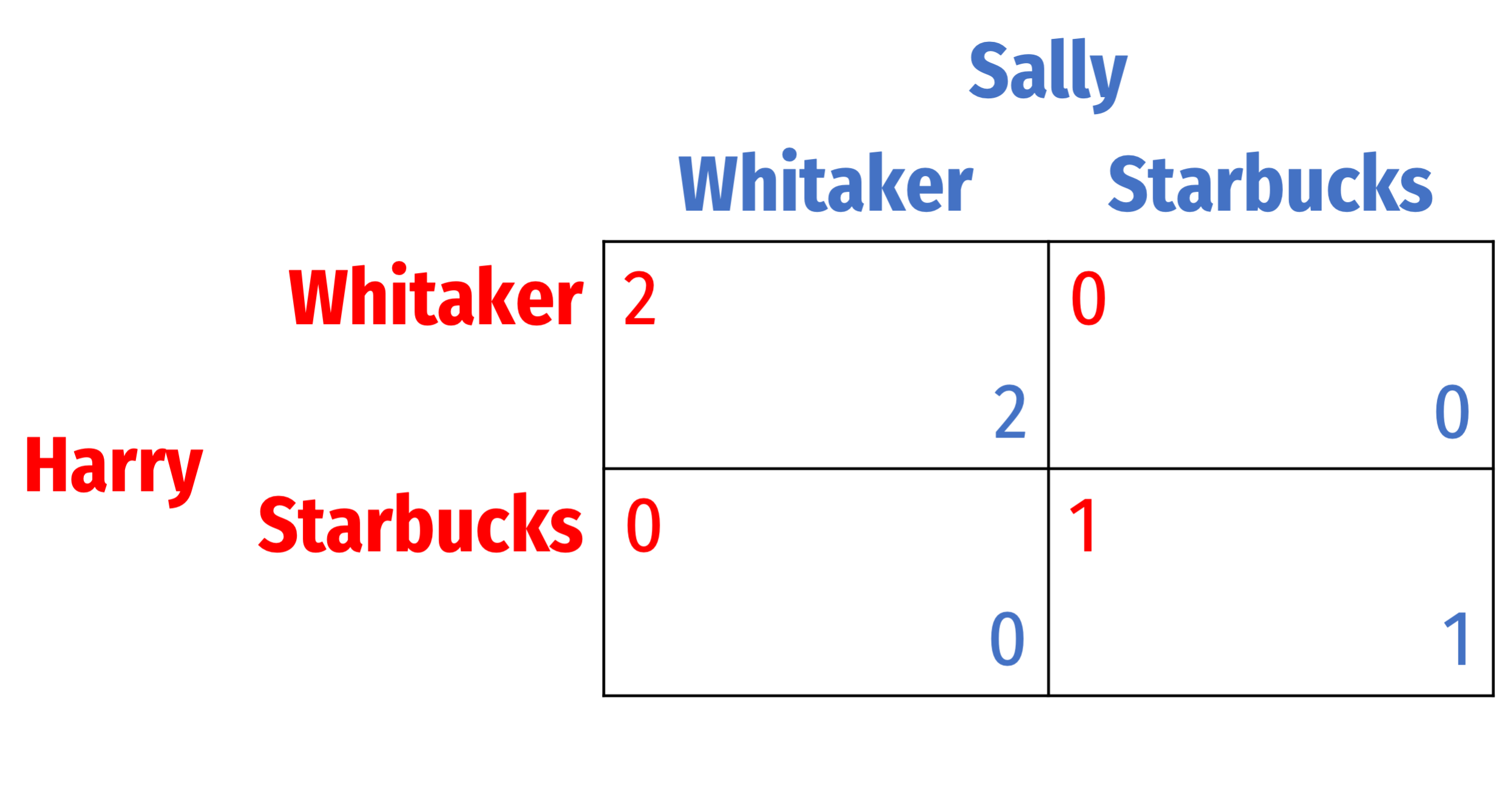

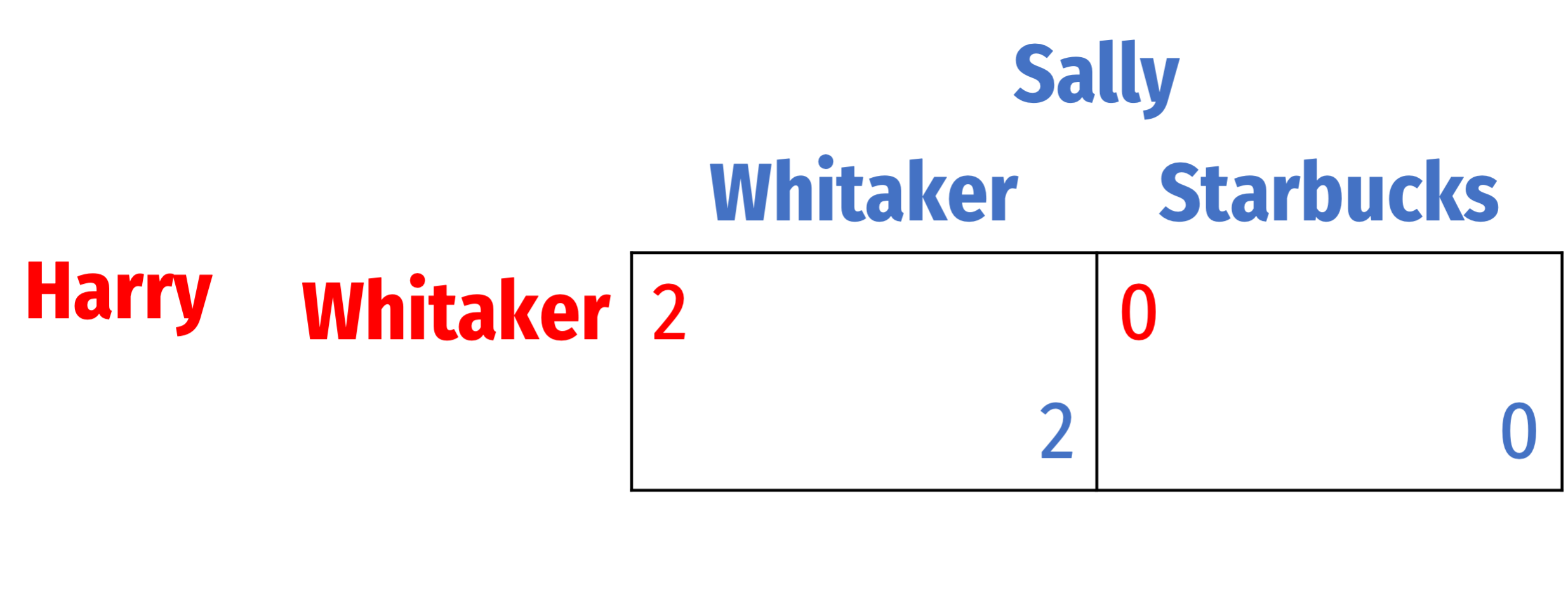

Take the Assurance game example

Suppose Harry publicly announces “I'm going to Whitaker” and then walks away (and turns off his phone), unable to be reached

Cut Off Communication

Take the Assurance game example

Suppose Harry publicly announces “I'm going to Whitaker” and then walks away (and turns off his phone), unable to be reached

If Sally believes him, she has little choice but to go to Whitaker

Cut off Communication

Stake Your Reputation on Performance

“Given the importance of credit sales, the diamond industry depends overwhelmingly on the reliable enforcement of executory contracts. However, while most industries employ state-sponsored courts to enforce payment after the delivery of goods, public courts are toothless to enforce credit sales for diamonds. Diamons are easily portable and command extreme value throughout the world. A diamond thief encounters little difficulty in hiding unpaid-for or stolen diamonds from law enforcement officials, fleeing American jurisdiction, and selling the valuable diamonds to black market buyers,” (p.392).

Richman, Barak D, 2006, “How Community Institutions Create Economic Advantage: Jewish Diamond Merchants in New York,” Law and Social Inquiry 31(2):383-420

Stake Your Reputation on Performance

“The failure of public courts requires diamond merchants to rely on trust-based exchange. Mutual trust among merchants -- which the New York Times has called "the real treasure of 47th street" -- assures dealers that by maintaining a trustworthy reputation, they will remain in good community standing and preserve the opportunity to engage in future lucrative transactions...despite the unreliability of state courts.,” (p.393).

Richman, Barak D, 2006, “How Community Institutions Create Economic Advantage: Jewish Diamond Merchants in New York,” Law and Social Inquiry 31(2):383-420

Burn Your Boats

Hernan Cortes and the Spanish conquistadors invade Mexico in the early 16th century, ruled by Aztecs

If both sides fight, worst outcome for both

- Spaniards have inferior numbers than Aztecs, heavier losses

If one side fights and the other runs, the fighter gets more than runner

If both sides run, nothing happens

Burn Your Boats

Hernan Cortes and the Spanish conquistadors invade Mexico in the early 16th century, ruled by Aztecs

If both sides fight, worst outcome for both

- Spaniards have inferior numbers than Aztecs, heavier losses

If one side fights and the other runs, the fighter gets more than runner

If both sides run, nothing happens

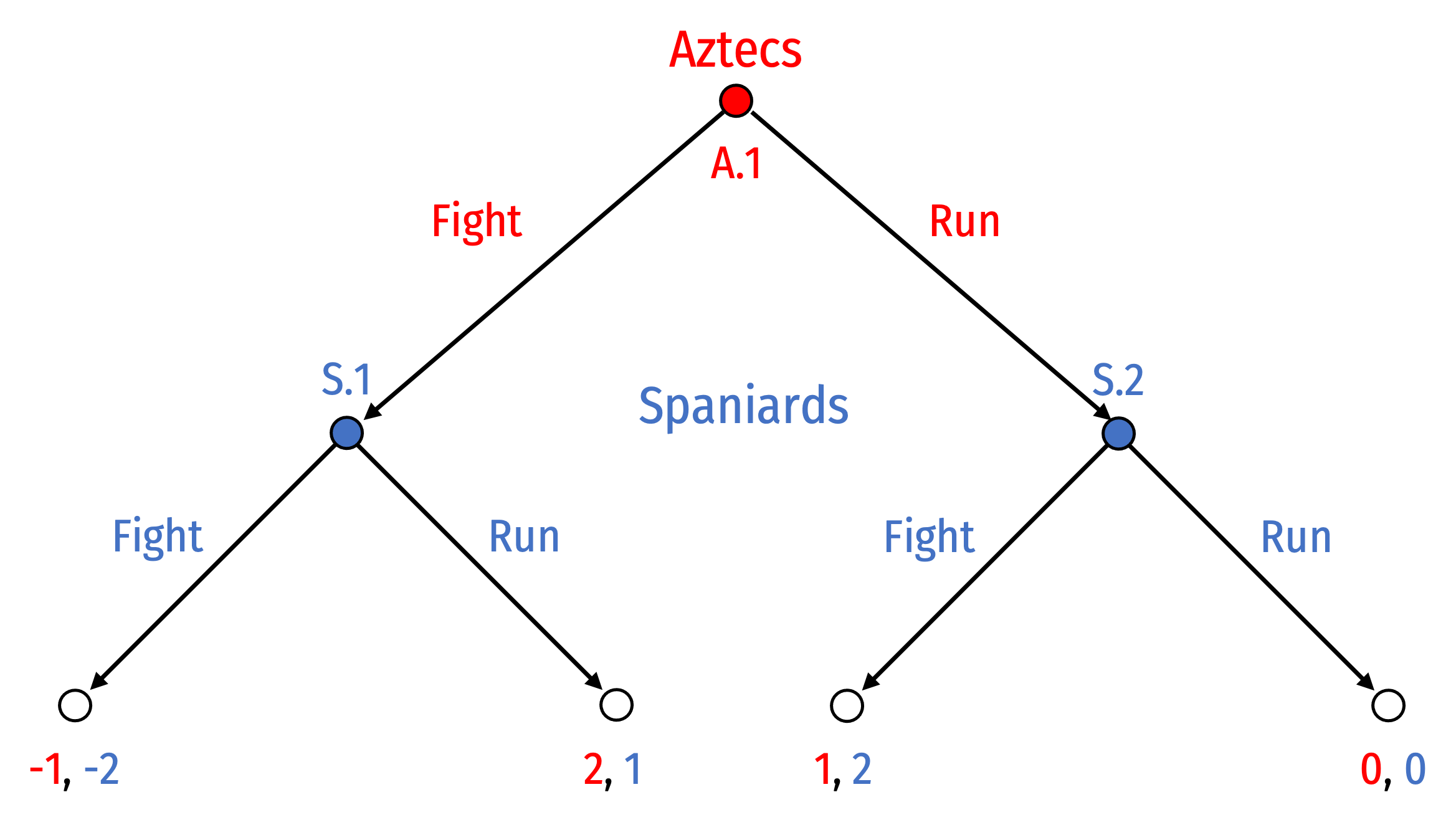

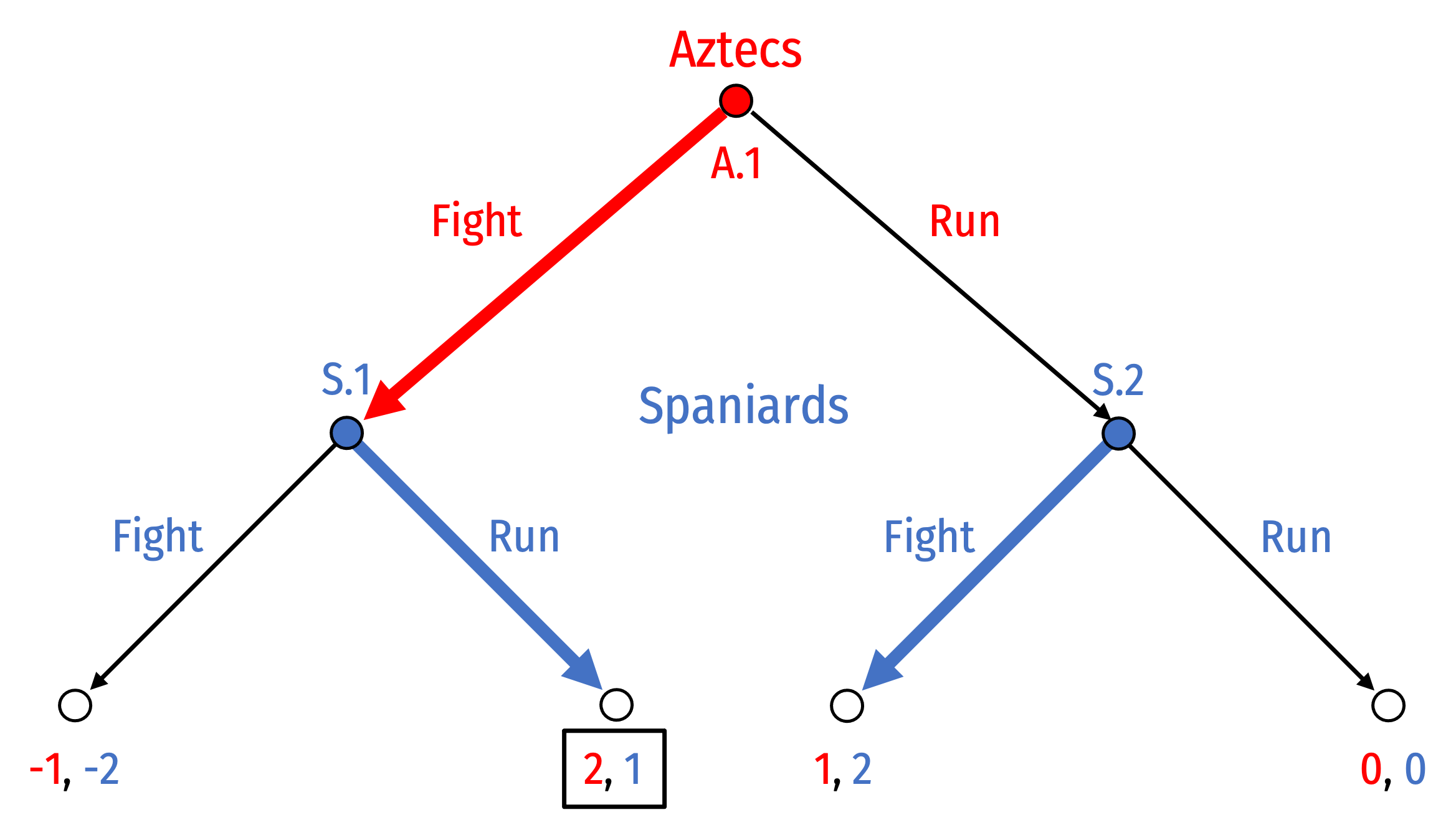

Burn Your Boats

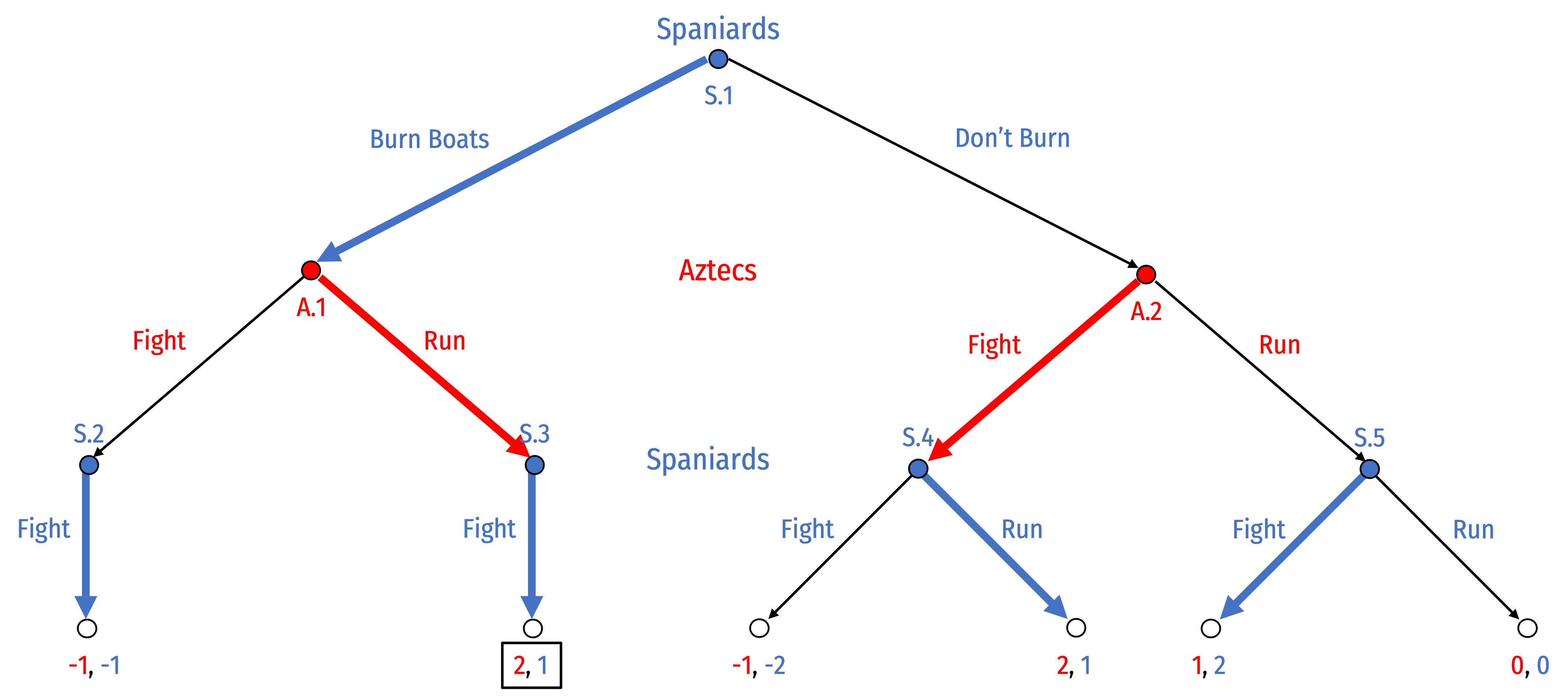

SNPE: {Fight, (Run, Fight)}

Spaniards lose

- and no credible threat to respond to Fight with Fight

Burn Your Boats

Cortes decides before the game begins to make a strategic move: burn his ships so his men cannot retreat

Removes option of Run for Spaniards

Burn Your Boats

Cortes decides before the game begins to make a strategic move: burn his ships so his men cannot retreat

Removes option of Run for Spaniards

Now resolve for SPNE

Burn Your Boats

SPNE: {(Run, Fight), (Burn, Fight, Fight, Run, Fight)}

Spaniards’ pre-game strategic move of Burn set them up for a superior outcome (for them): Burn → Run → Fight

This Is a Classic Military Tactic

“If you want to take the island, burn the boats.” — Julius Caesar before his invasion of Britannia (55 B.C.)

This Is a Classic Military Tactic

“At the critical moment, the leader of an army acts like one who has climbed up a height, and then kicks away the ladder behind him” — Sun Tzu, The Art of War (c.500 B.C.)

Take the Result out of Your Hands

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“Making a credible threat involves proving that one would have to carry out the threat, or creating incentives for oneself or incurring penalties that would make one evidently want to. The acknowledged purpose of stationing American troops in Europe as a “trip wire” was to convince the Russians that war in Europe would involve the United States whether the Russians thought the United States wanted to be involved or not -- that escape from the commitment was physically impossible.” (p.187).

Take the Result out of Your Hands

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“The key to these threats is that, though one party may or may not carry them out if the threatened party fails to comply, the final decision is not altogether under the threatener's control,” (p.187).

Schelling, Thomas, 1960, The Strategy of Conflict

Take the Result out of Your Hands

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“Ideally, for this purpose, I should have a little black box that contains a roulette wheel and a device that will detonate in a way that unquestionably provokes total war...I tell [the Russians]—demonstrate to them—that the little box will keep running until my demands have been complied with and that there is nothing I can do to stop it...Note that I do not insist that I shall decide on total war...I leave it all up to the box which automatically engulfs us both in war if the right (wrong) combination comes up on any day.” (p.197).

Schelling, Thomas, 1960, The Strategy of Conflict

Take the Result out of Your Hands

Thomas Schelling

1921—2016

Economics Nobel 2005

“Brinkmanship is thus the deliberate creation of a recognizable risk of war, a risk that one does not completely control. It is the tactic of deliberately letting the situation get somewhat out of hand, just because its being out of hand may be intolerable to the other party and force his accomodation. It means harassing and intimidating an adversary by exposing him to a shared risk, or deterring him by showing that if he makes a contrary move he may disturb us so that we slip over the brink whether we want to or not, carrying him with us,” (p.200).

Schelling, Thomas, 1960, The Strategy of Conflict

The Doomsday Device

Threats and Applications

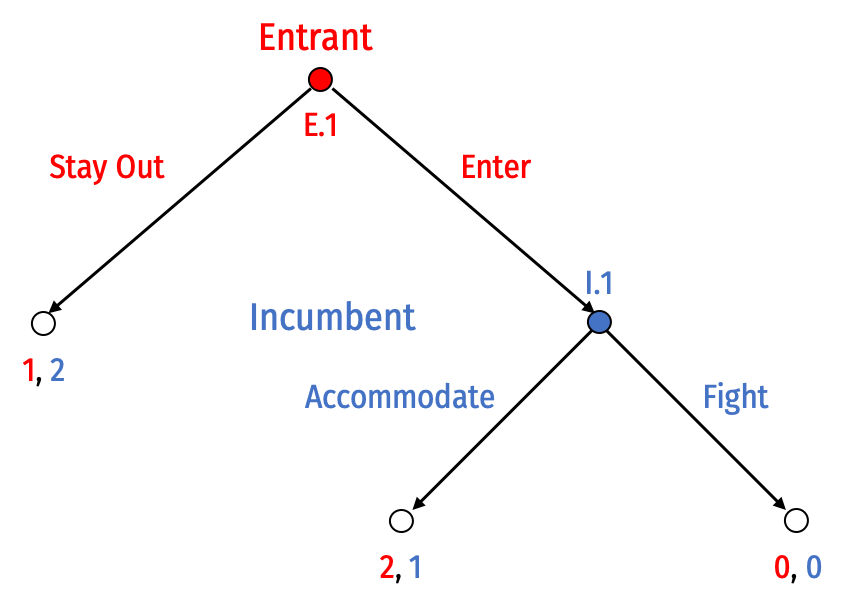

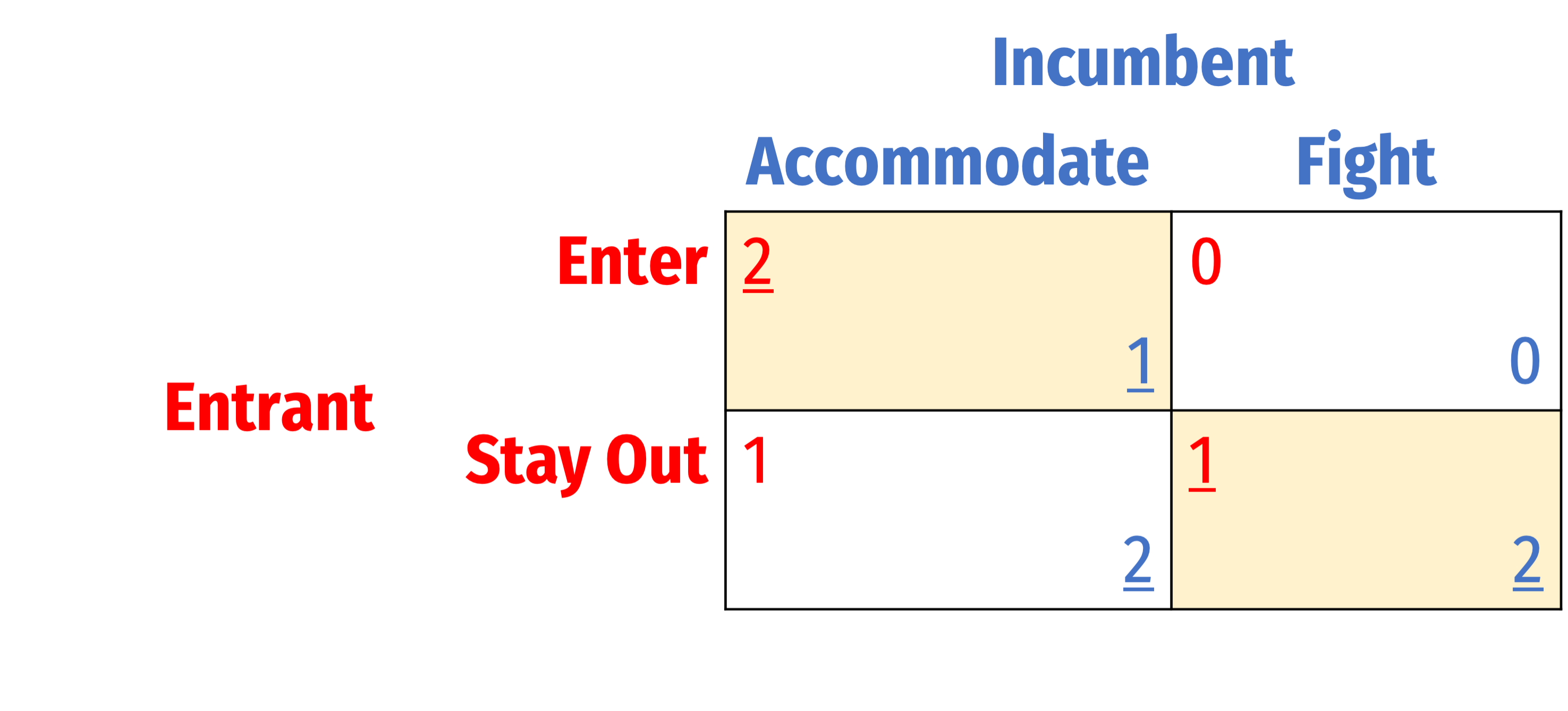

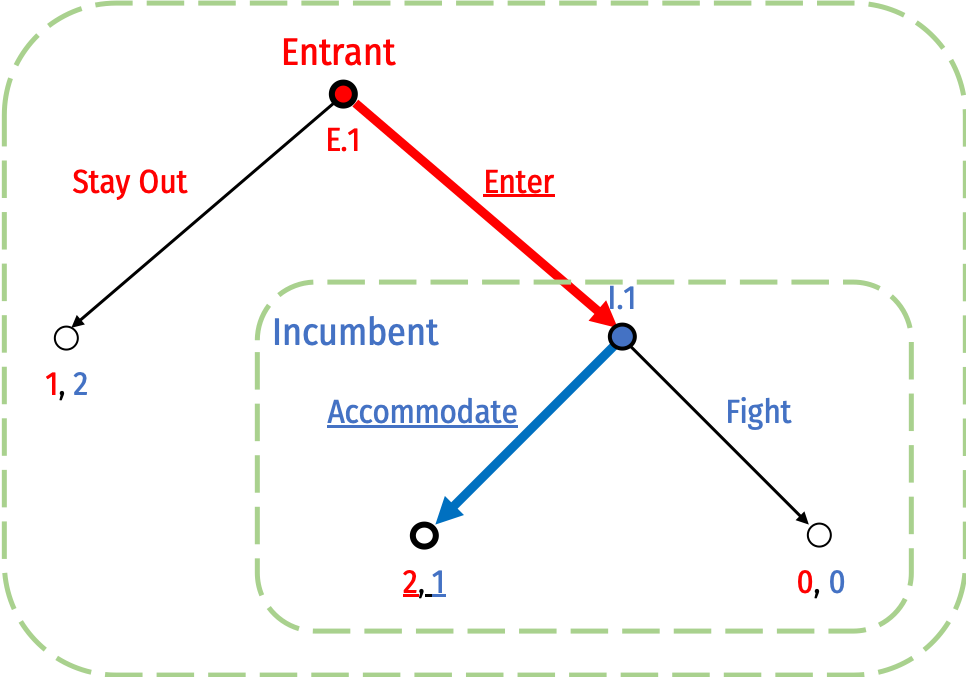

Threats: Entry Game Example

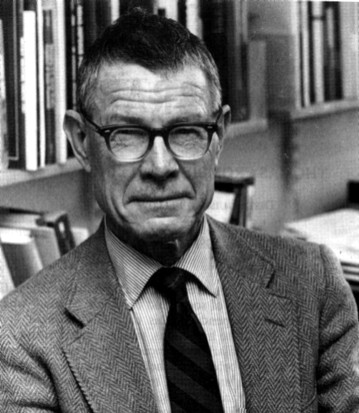

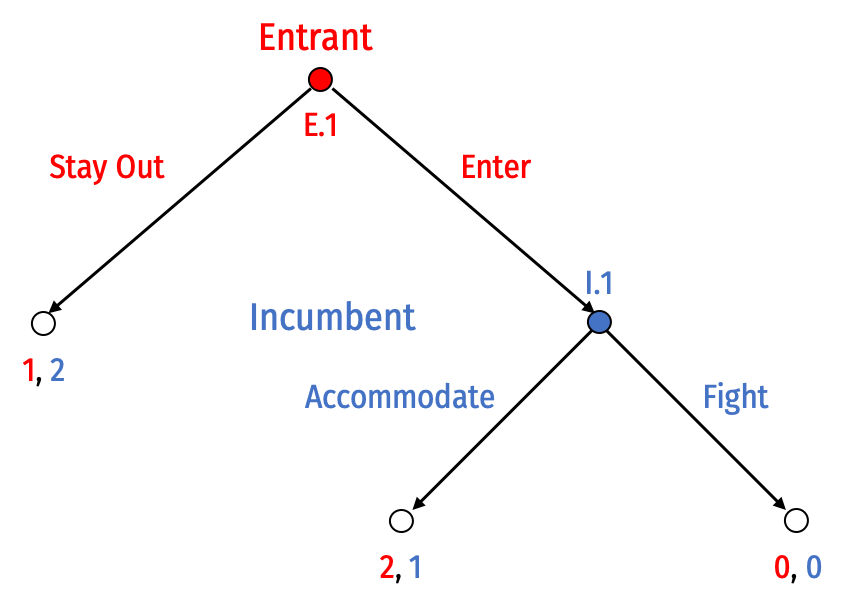

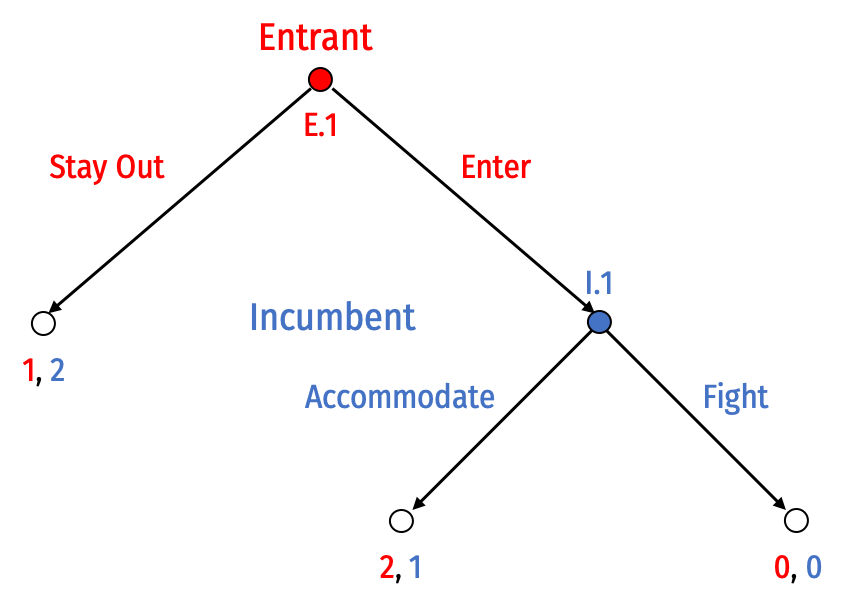

- Consider our Entry Game, between a potential Entrant and an Incumbent, from before

Threats: Entry Game Example

- Consider our Entry Game, between a potential Entrant and an Incumbent, from before

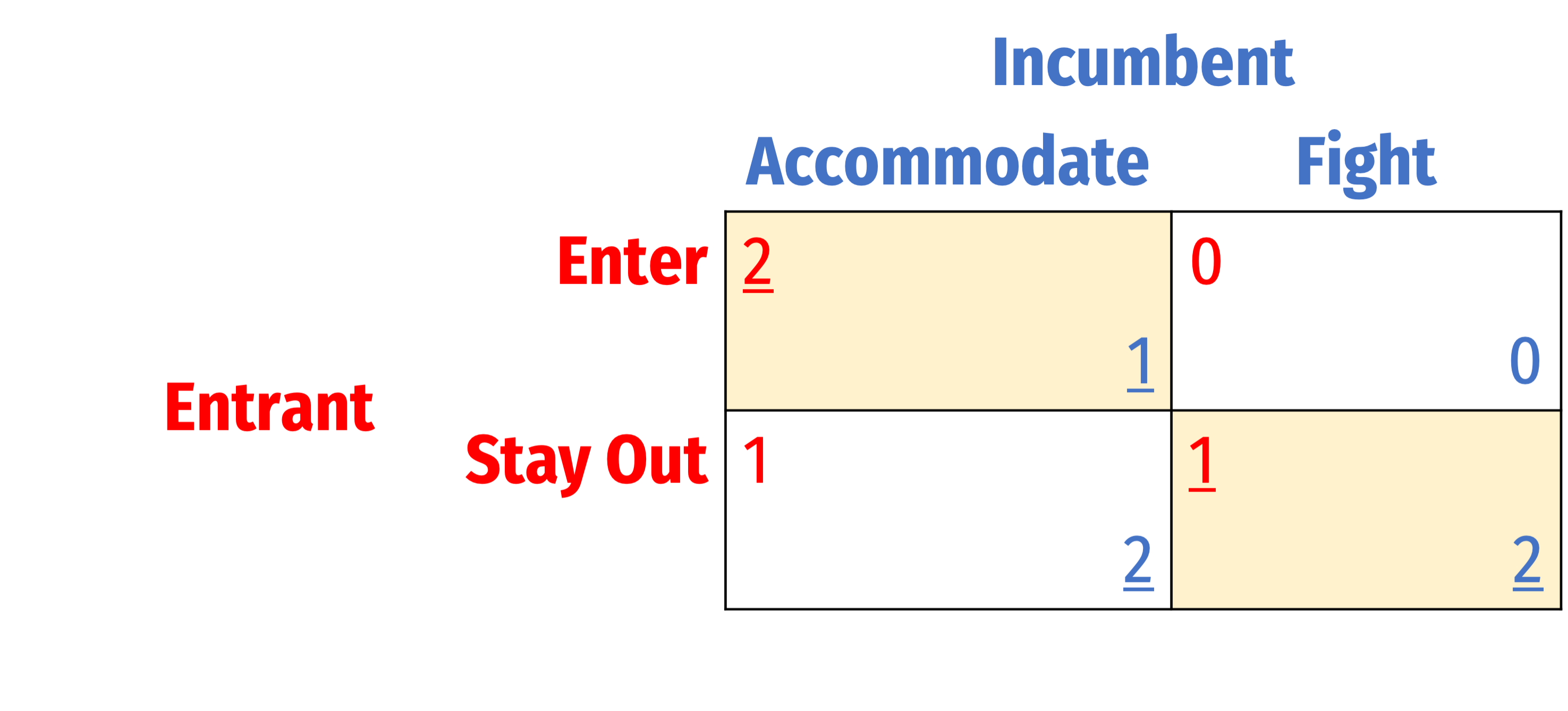

Threats: Entry Game Example

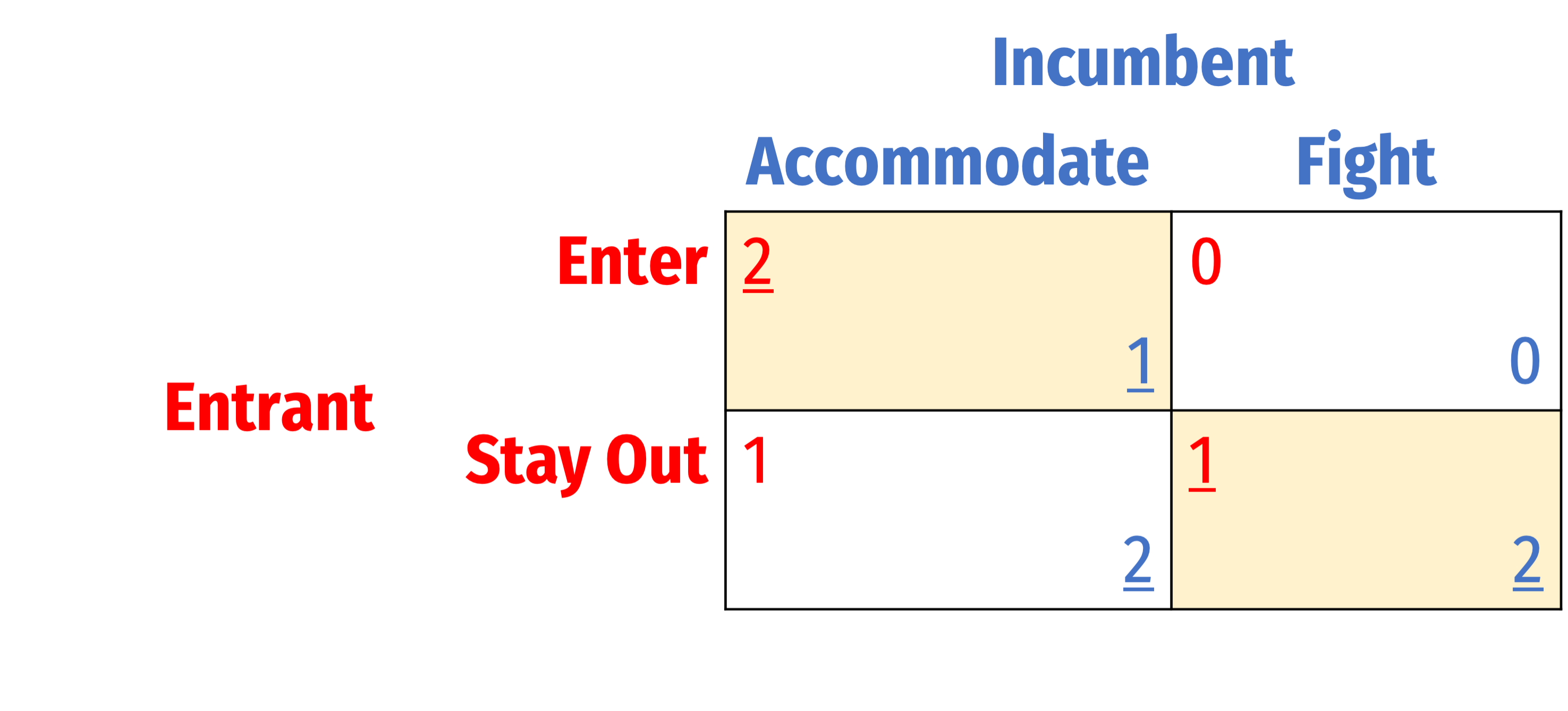

- Two Nash Equilibria:

- (Enter, Accommodate)

- (Stay Out, Fight)

Threats: Entry Game Example

- Two Nash Equilibria:

- (Enter, Accommodate)

- (Stay Out, Fight)

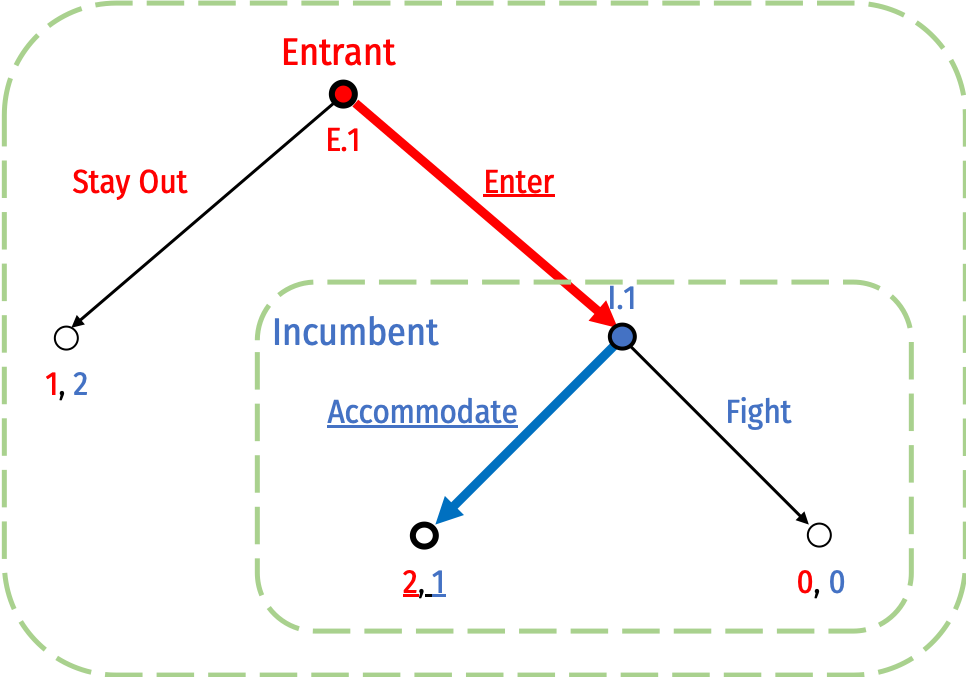

Only (Enter, Accommodate) is a Subgame Perfect Nash Equilibrium (SPNE)

These strategy profiles for each player constitute a Nash equilibrium in every possible subgame!

Threats: Entry Game Example

- Suppose before the game started, Incumbent announced to Entrant

“if you Enter, I will Fight!”

This threat is not credible because playing Fight in response to Enter is not rational!

The strategy is not Subgame Perfect!

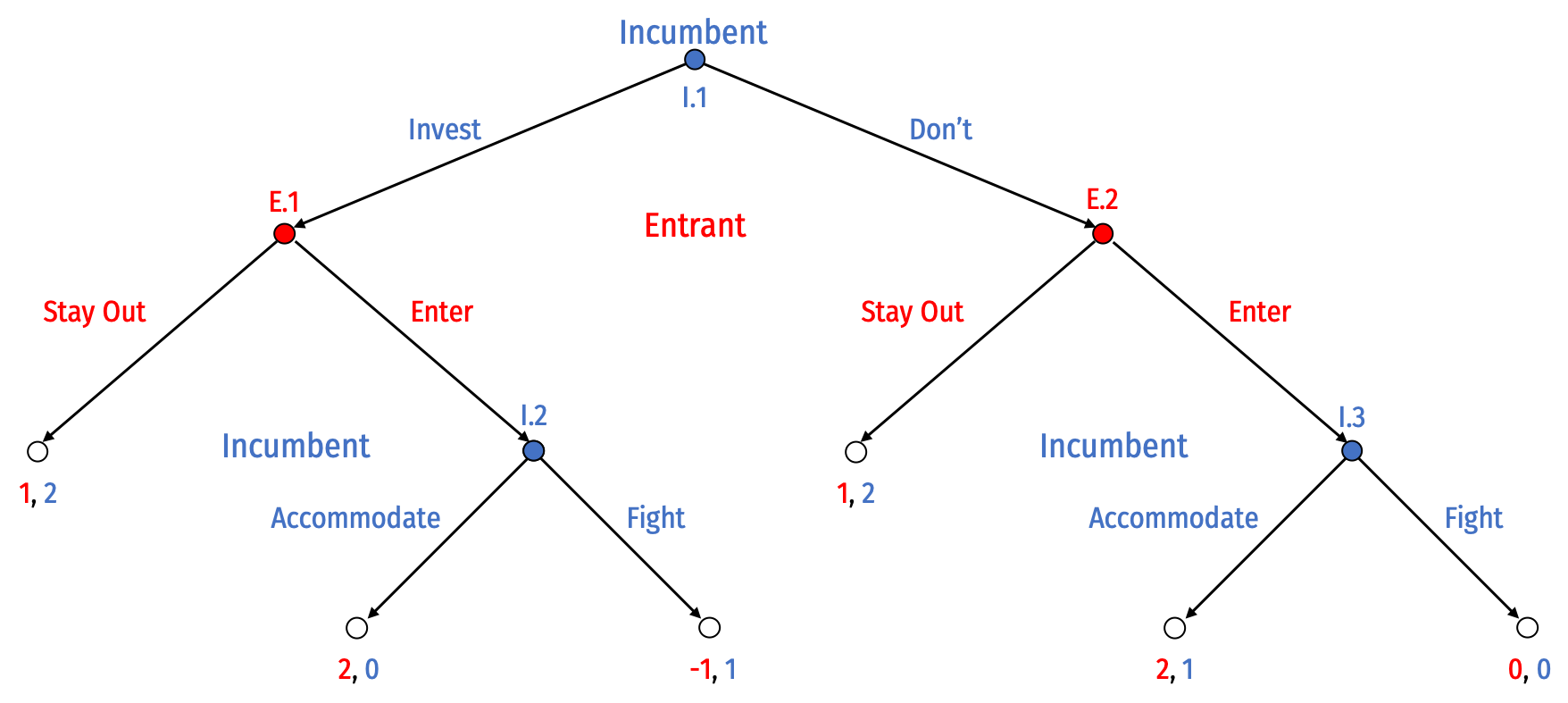

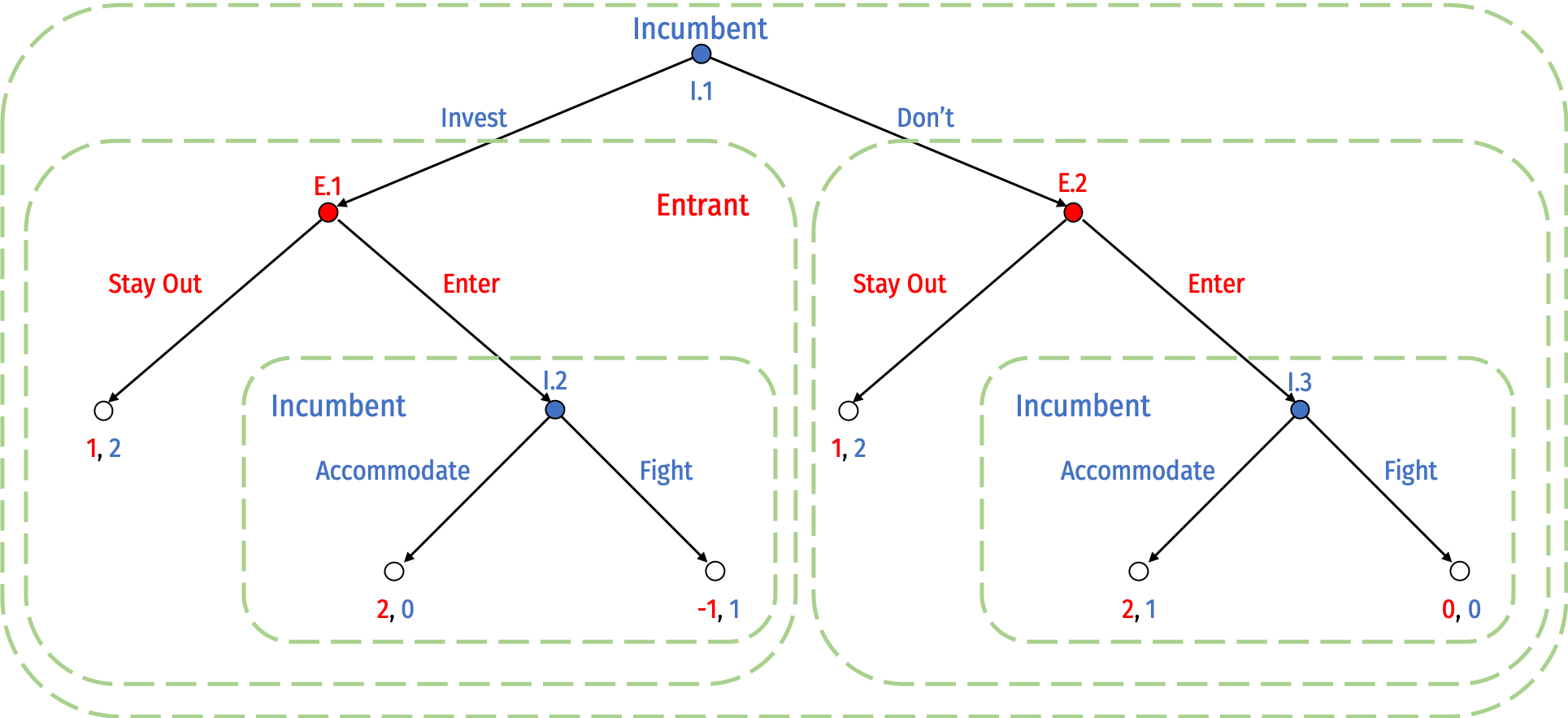

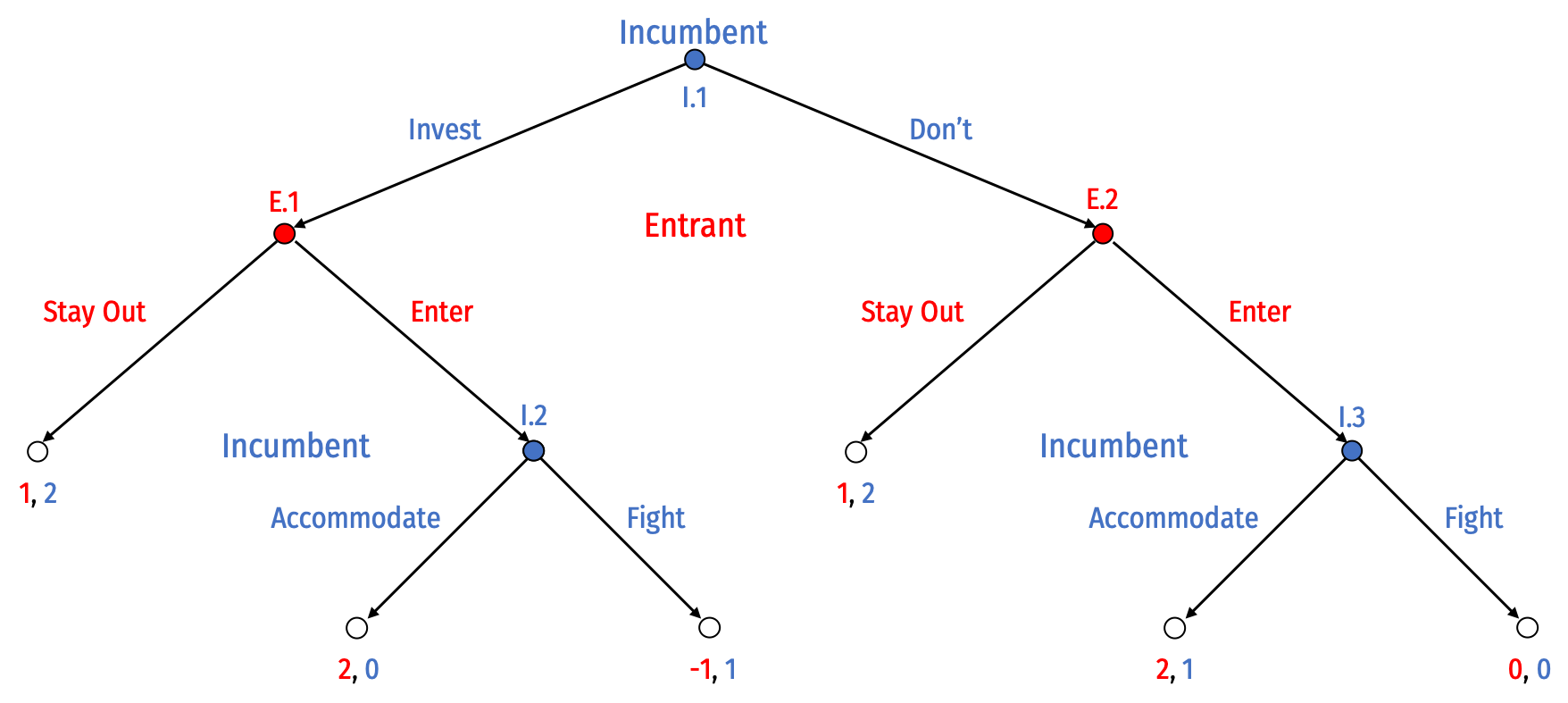

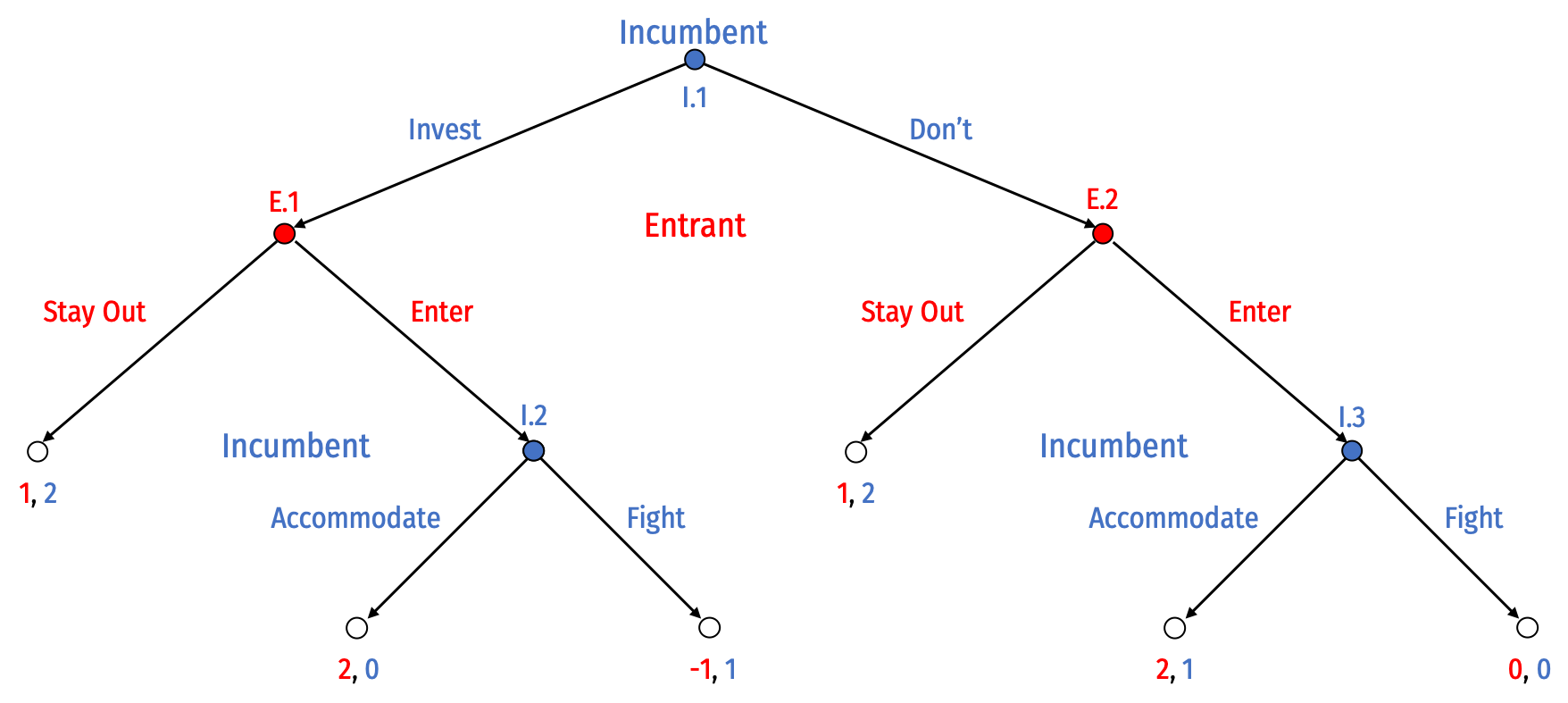

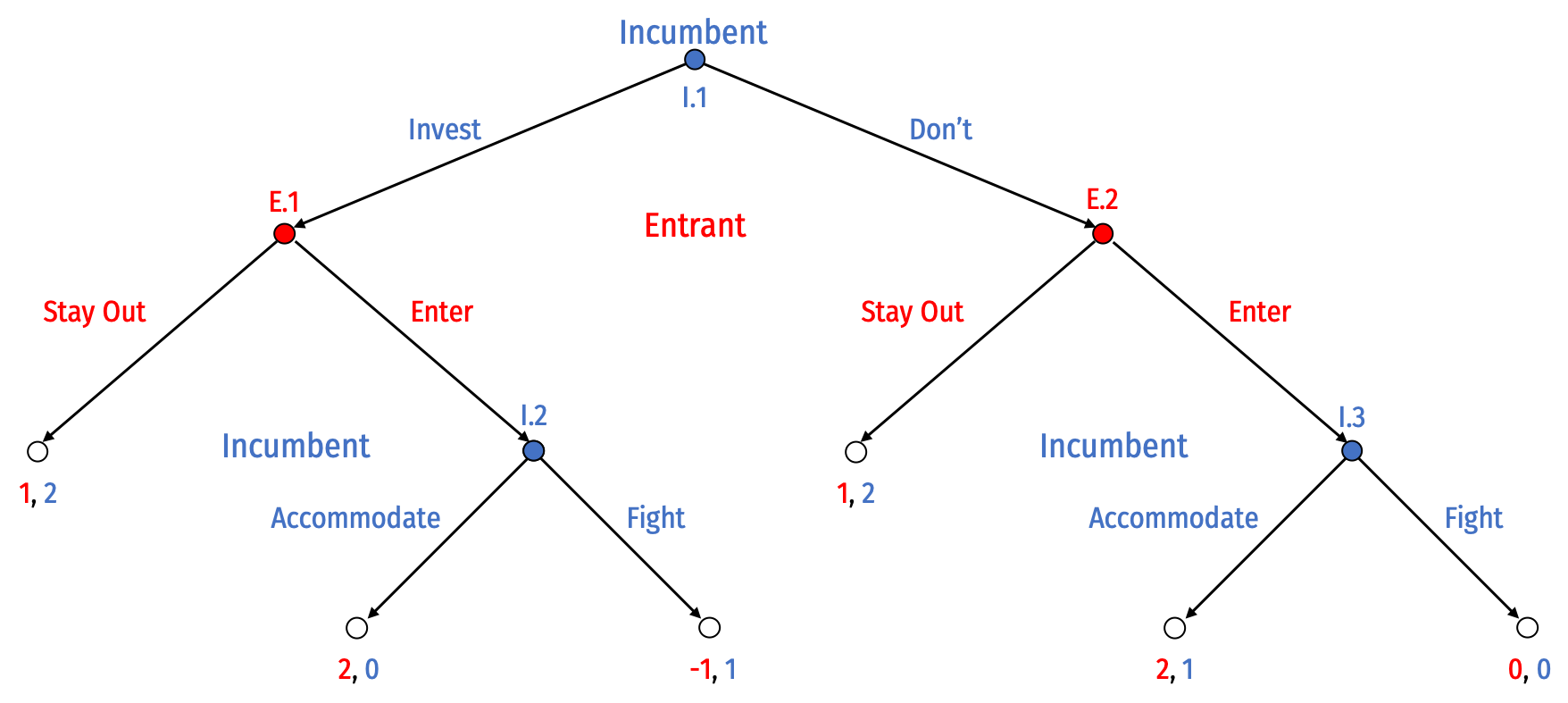

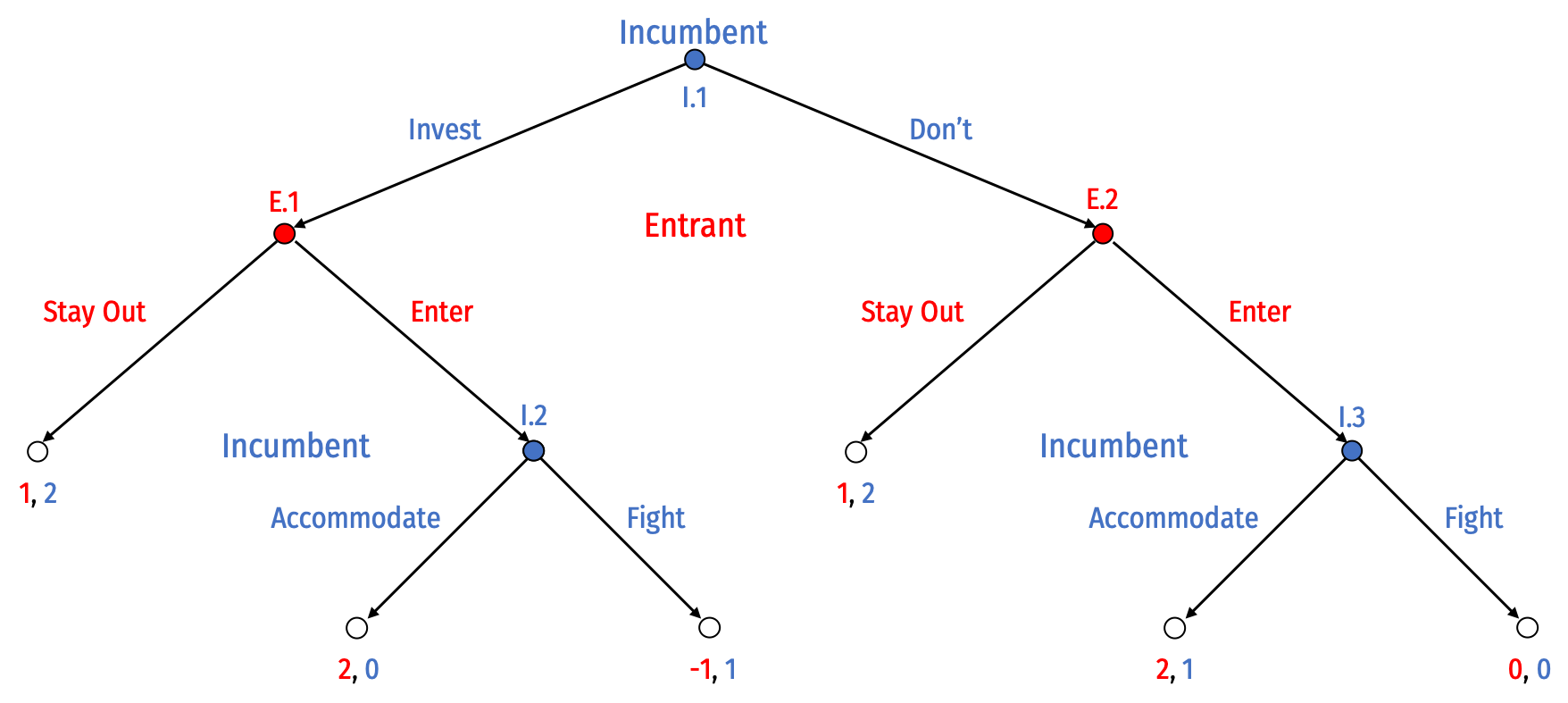

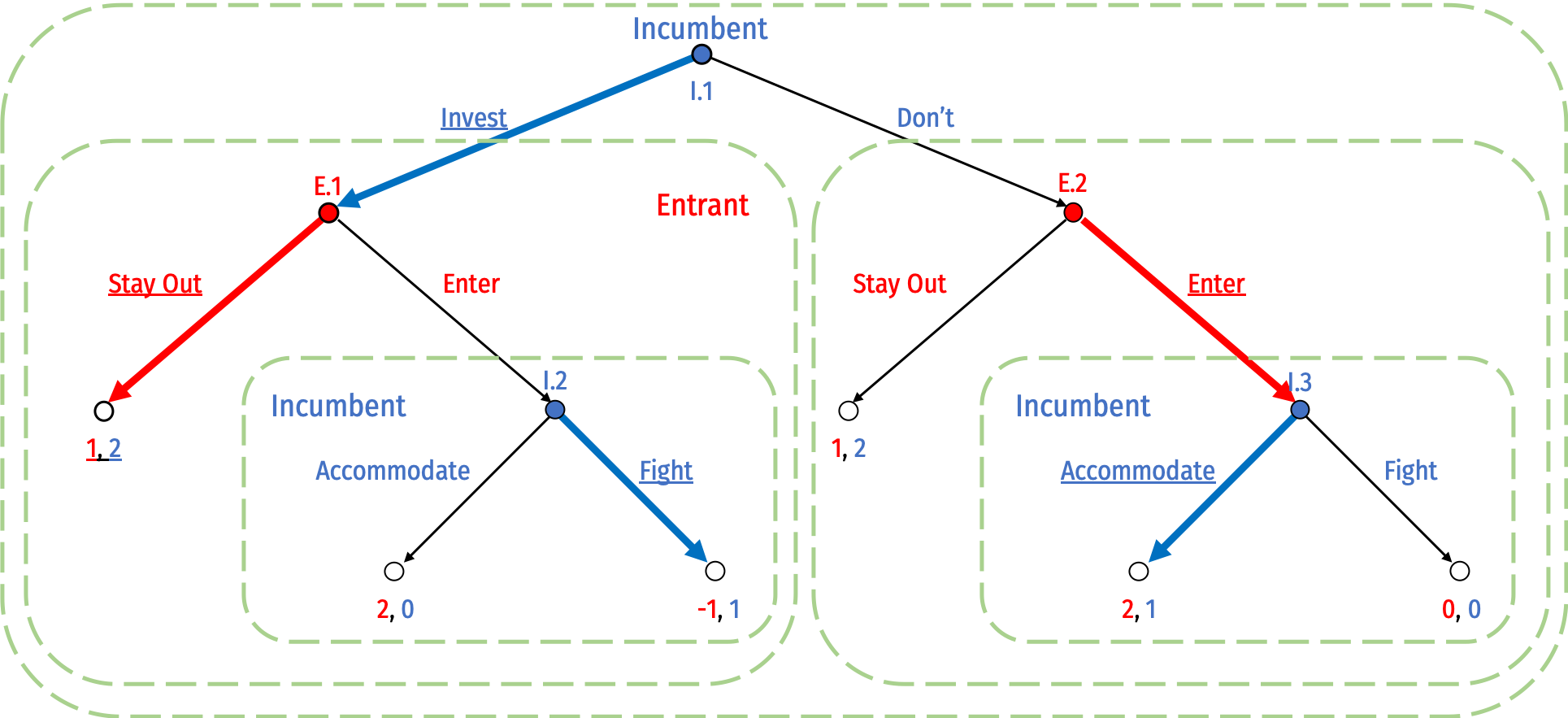

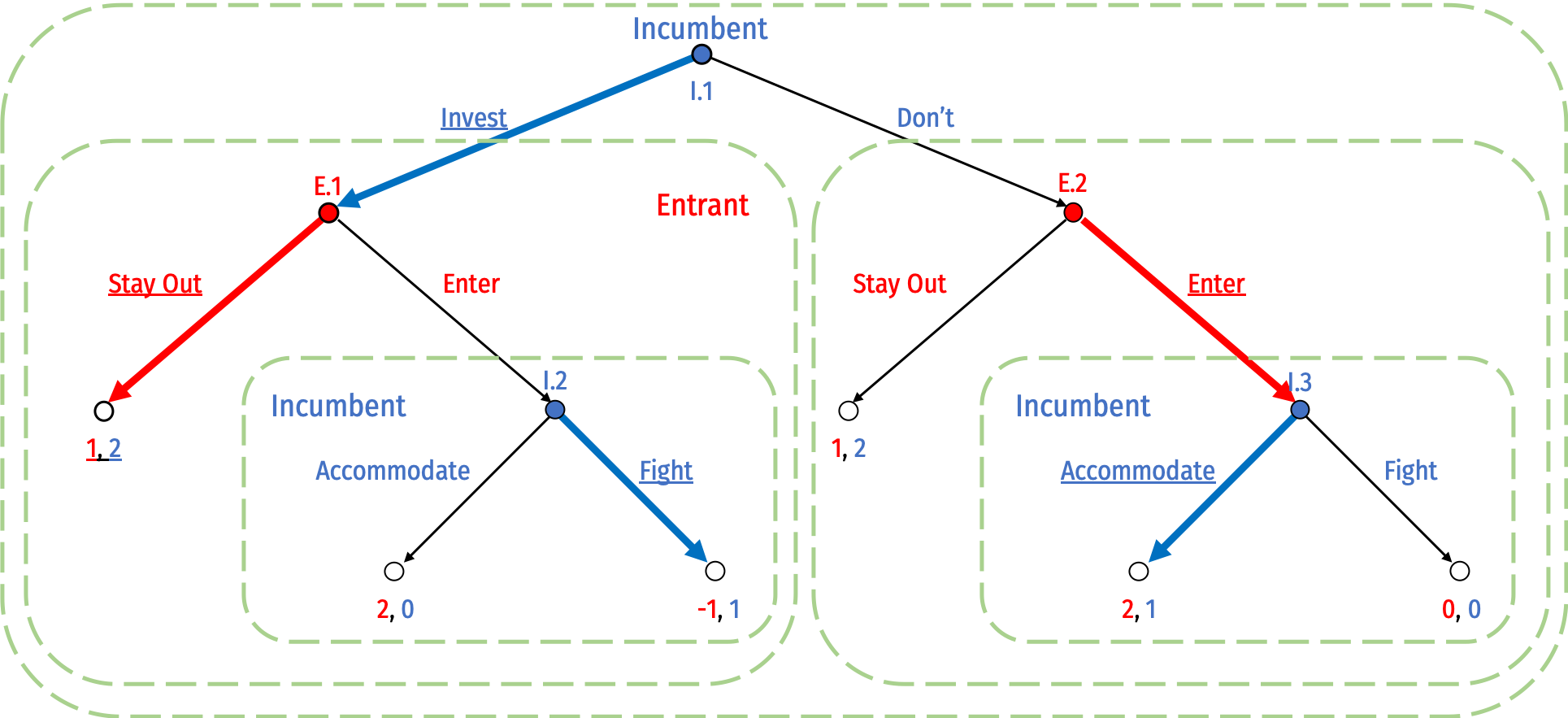

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

Suppose before the game started, Incumbent could decide whether or not to Invest in excess capacity

This is costly, suppose Incumbent incurs a cost of -1

Builds up a “war chest” allowing Incumbent to survive a price war

Now suppose Incumbent makes same threat to Entrant:

“if you Enter, I will Fight!”

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

Game changes, a first stage where Incumbent goes first at (new) I.1, deciding whether to Invest or Don't

- Game is the same as before from E.2 onwards

This is a more complicated game, let's apply what we've learned about subgame perfection...

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

- What are the subgames?

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

- What are the subgames?

- Subgame initiated by node I.1 (game itself)

- Subgame initiated by node E.1

- Subgame initiated by node E.2

- Subgame initiated by node I.2

- Subgame initiated by node I.3

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

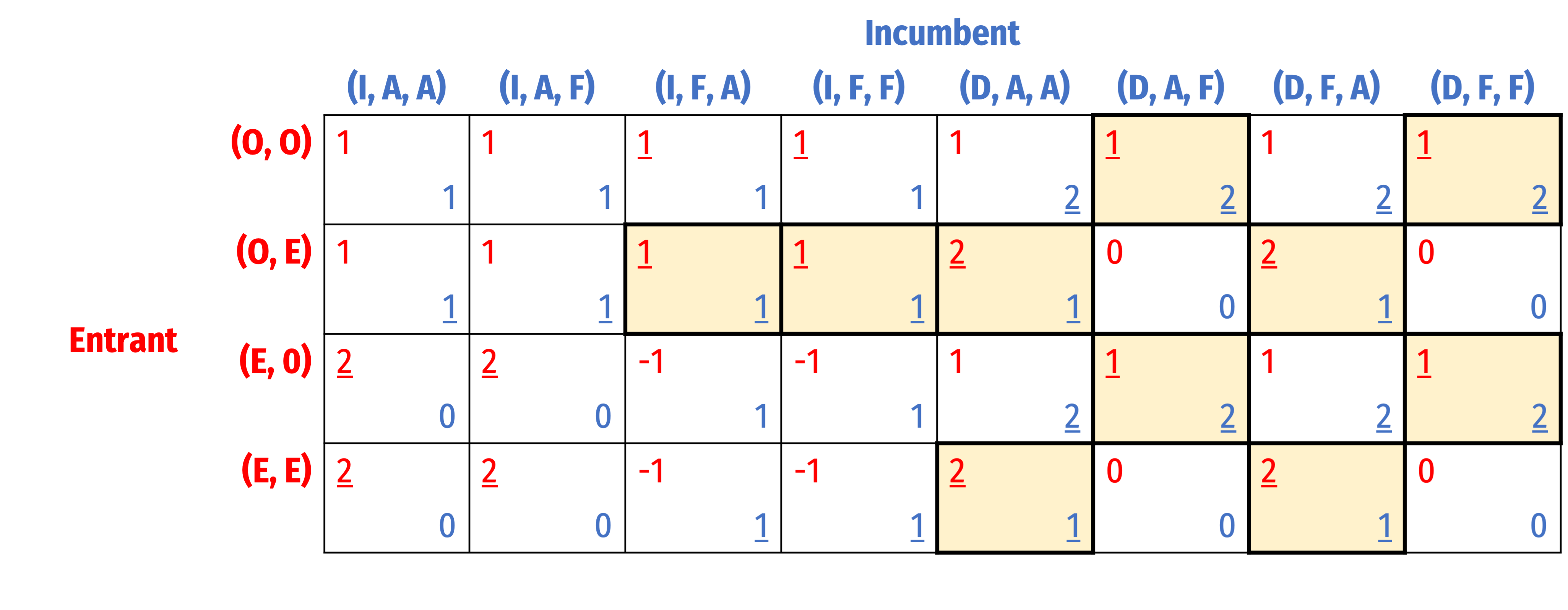

- What are the strategies available to each player?

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

What are the strategies available to each player?

Entrant, choosing at nodes (E.1, E.2)

- (Stay Out, Stay Out)

- (Stay Out, Enter)

- (Enter, Stay Out)

- (Enter, Enter)

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

What are the strategies available to each player?

Incumbent, choosing at nodes (I.1, I.2, I.3)

- (Invest, Accommodate, Accommodate)

- (Invest, Accommodate, Fight)

- (Invest, Fight, Accommodate)

- (Invest, Fight, Fight)

- (Don't, Accommodate, Accommodate)

- (Don't, Accommodate, Fight)

- (Don't, Fight, Accommodate)

- (Don't, Fight, Fight)

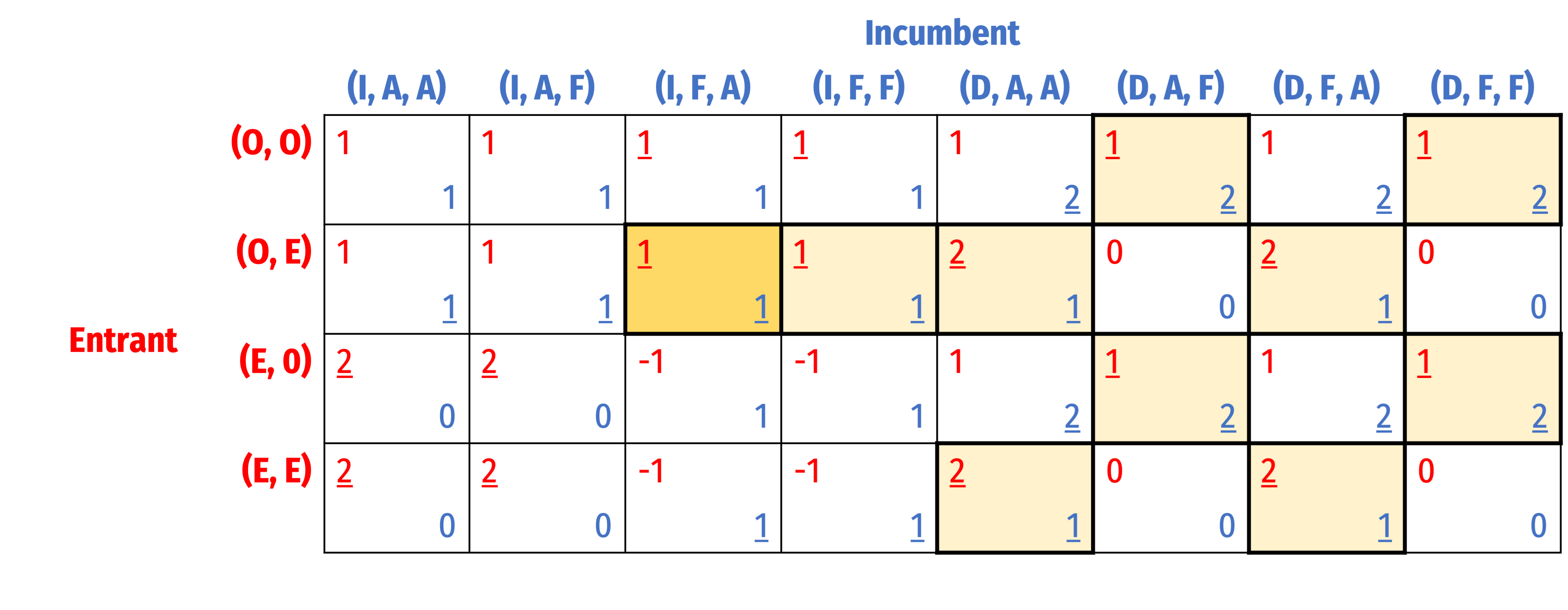

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

- Nash equilibria:

- {(O,O), (D,A,F)}

- {(O,O), (D,F,F)}

- {(O,E), (I,F,A)}

- {(O,E), (I,F,F)}

- {(O,E), (D,A,A)}

- {(O,E), (D,F,A)}

- {(E,O), (D,A,F)}

- {(E,O), (D,F,F)}

- {(E,E), (D,A,A)}

- {(E,E), (D,F,A)}

...which is subgame perfect?

Solve for all NE

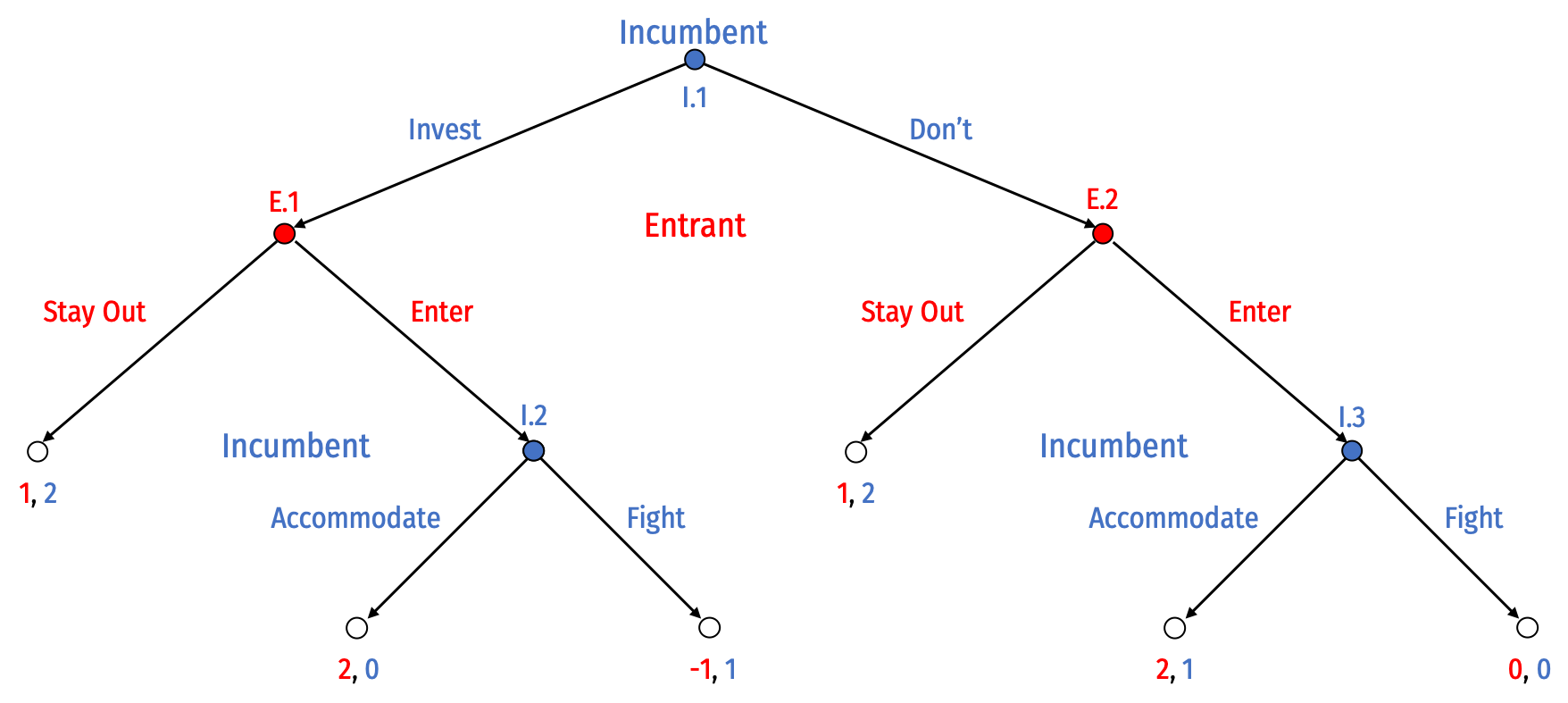

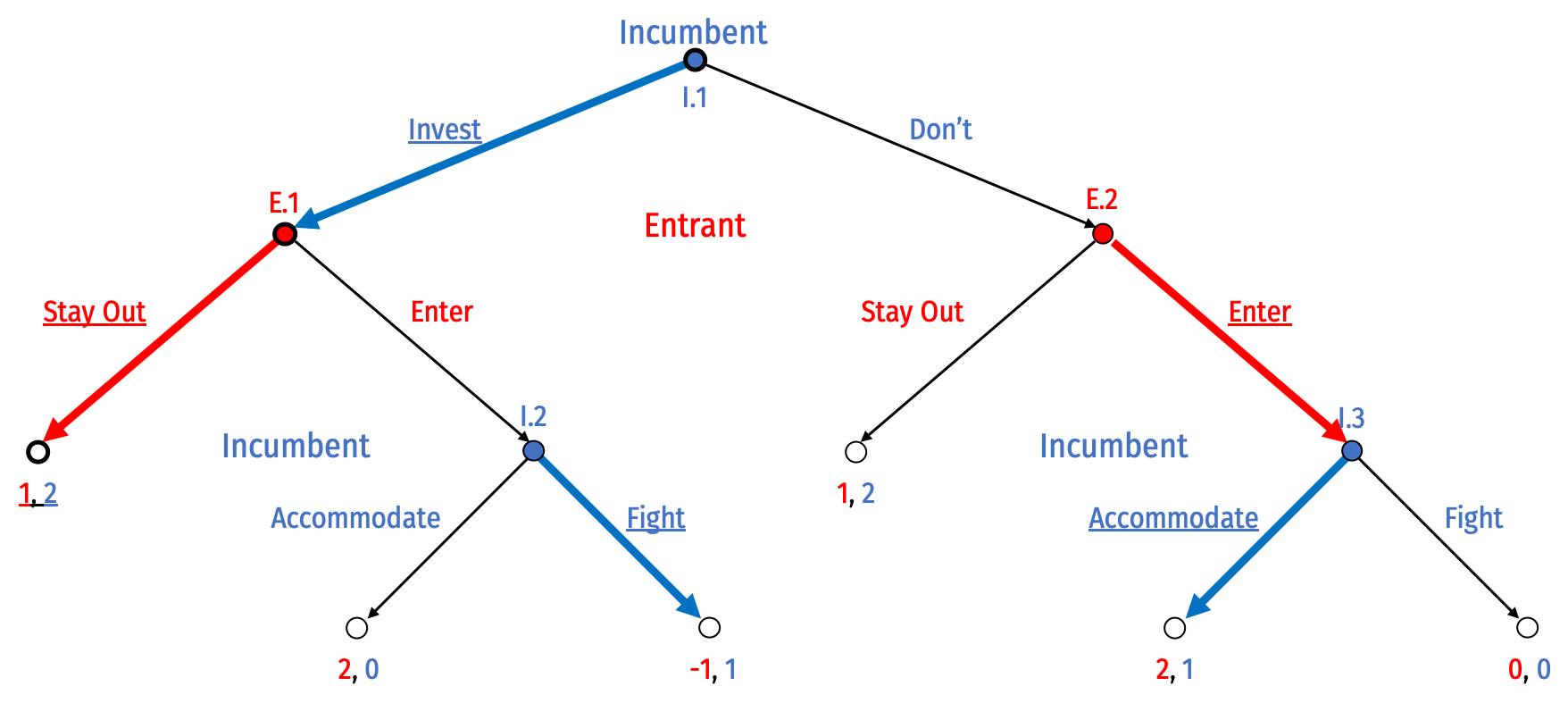

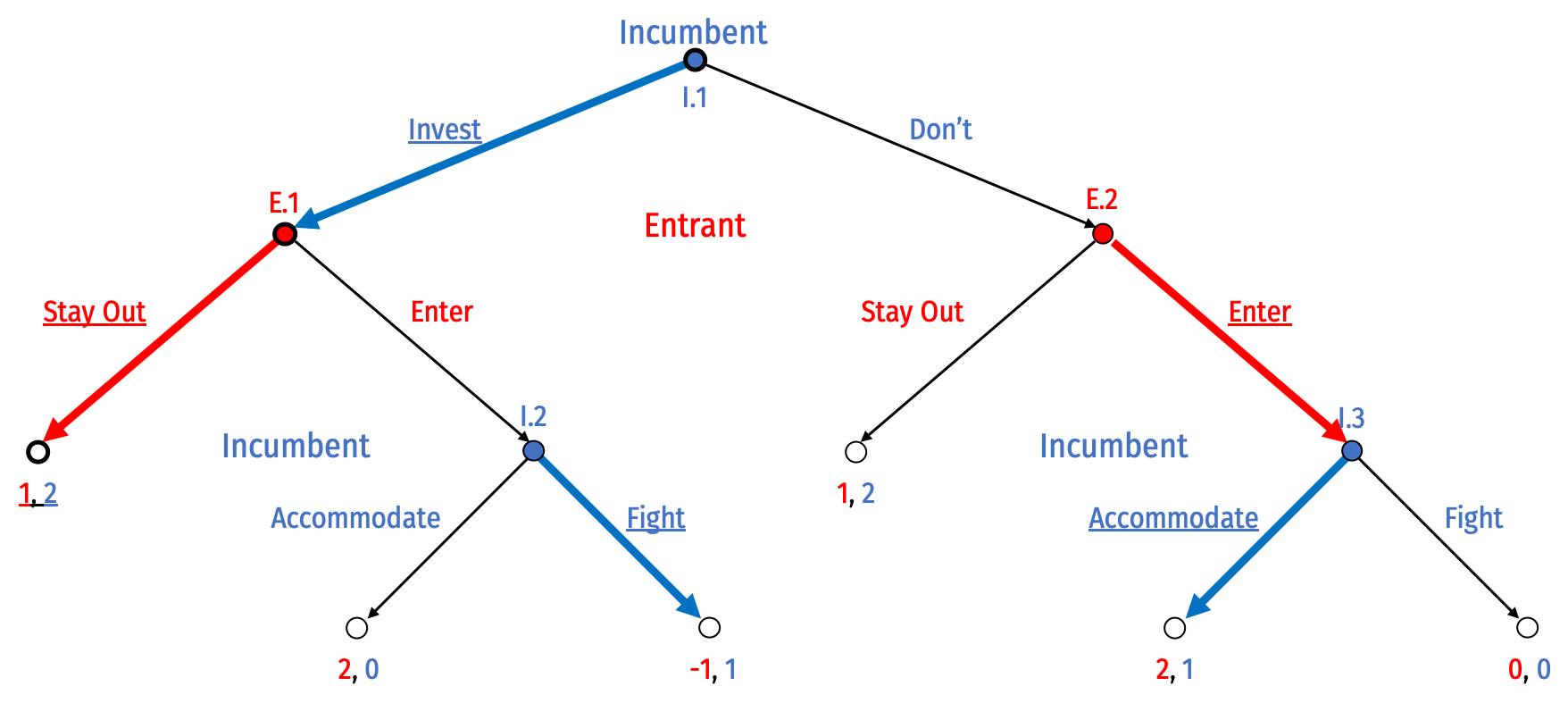

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

- Solve the game in sequential form via backward induction

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

Solve the game in sequential form via backward induction

SPNE: {(O,E), (I,F,A)}

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

SPNE: {(O,E), (I,F,A)}

This set of strategies induces a Nash equilibrium in all (5) subgames

Threats: Entry Game Example with Commitment

- Recall Incumbent’s threat to Entrant

“if you Enter, I will Fight!”

- With commitment, it is credible for Incumbent to threaten to Fight if Entrant decides to Enter!

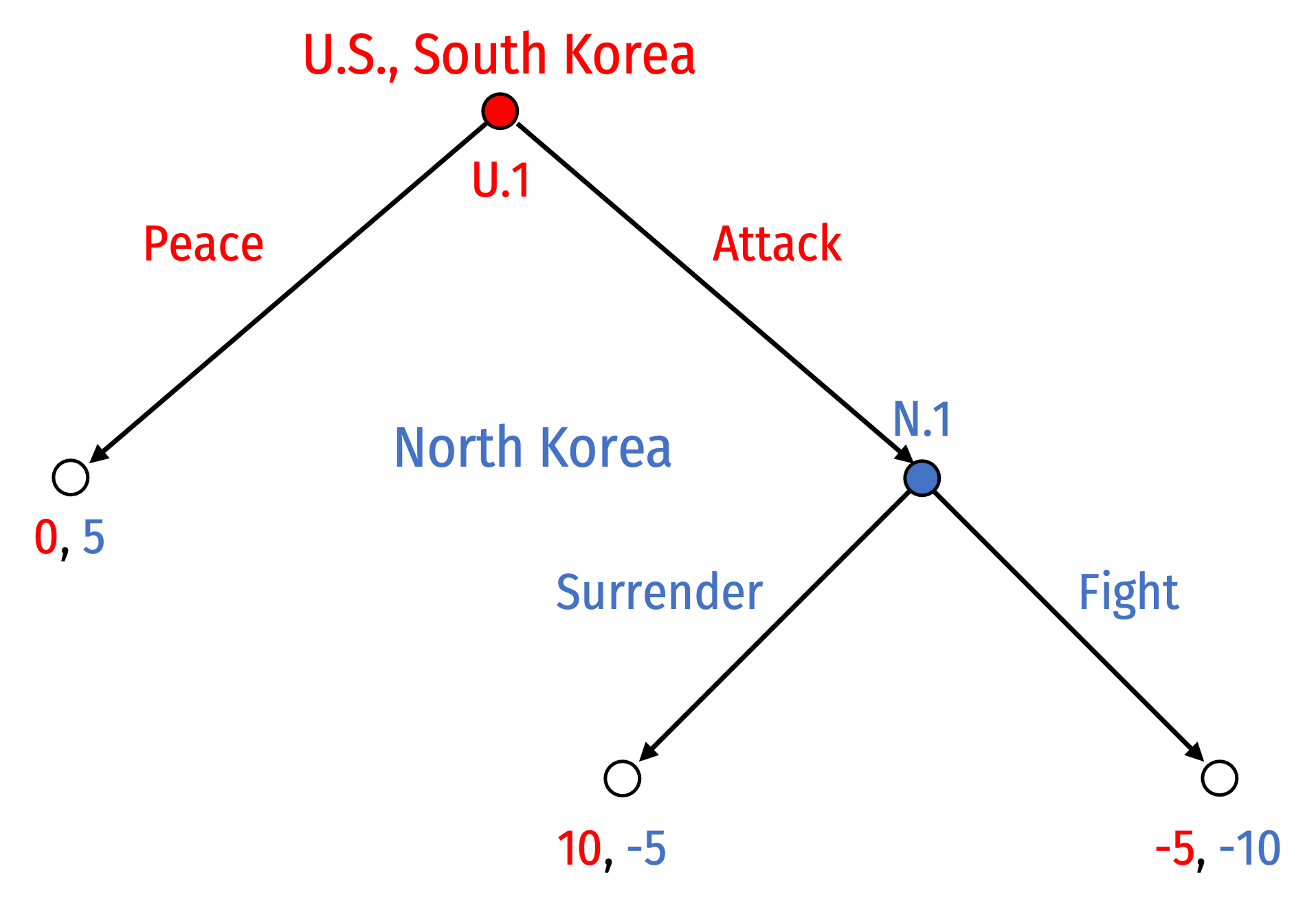

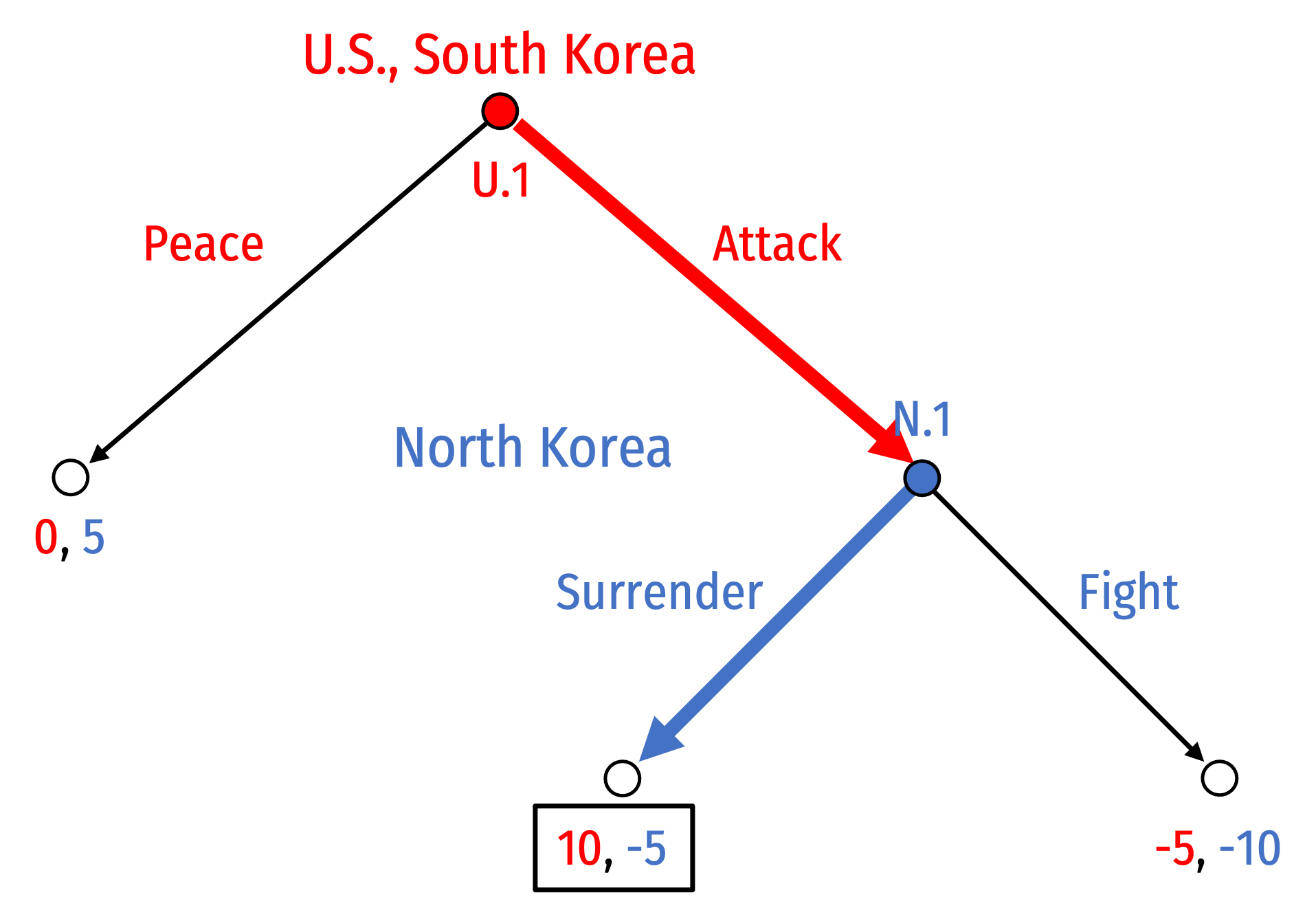

Why The U.S. Hasn’t Bombed North Korea

- Why hasn’t the U.S. bombed North Korea?

Why The U.S. Hasn’t Bombed North Korea

- Why hasn’t the U.S. bombed North Korea?

Why The U.S. Hasn’t Bombed North Korea

Why The U.S. Hasn’t Bombed North Korea

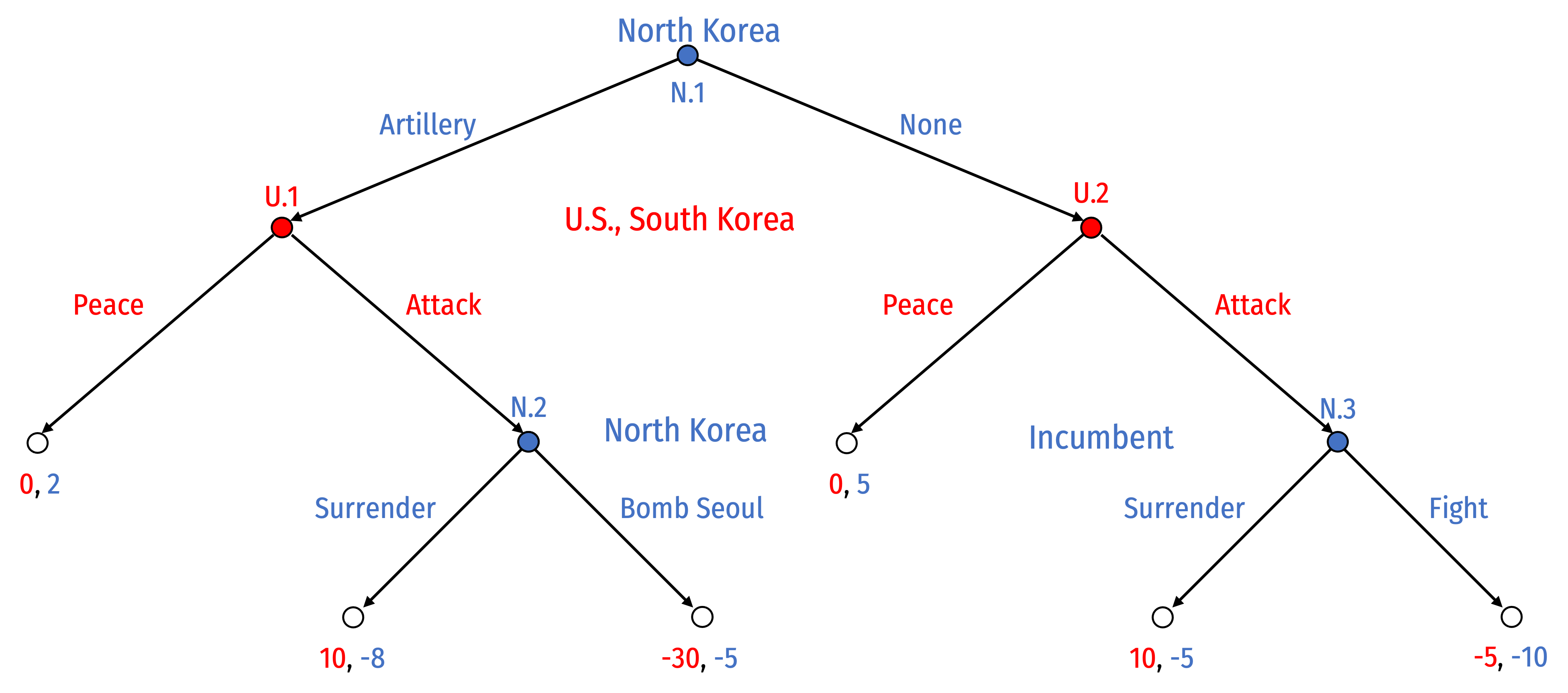

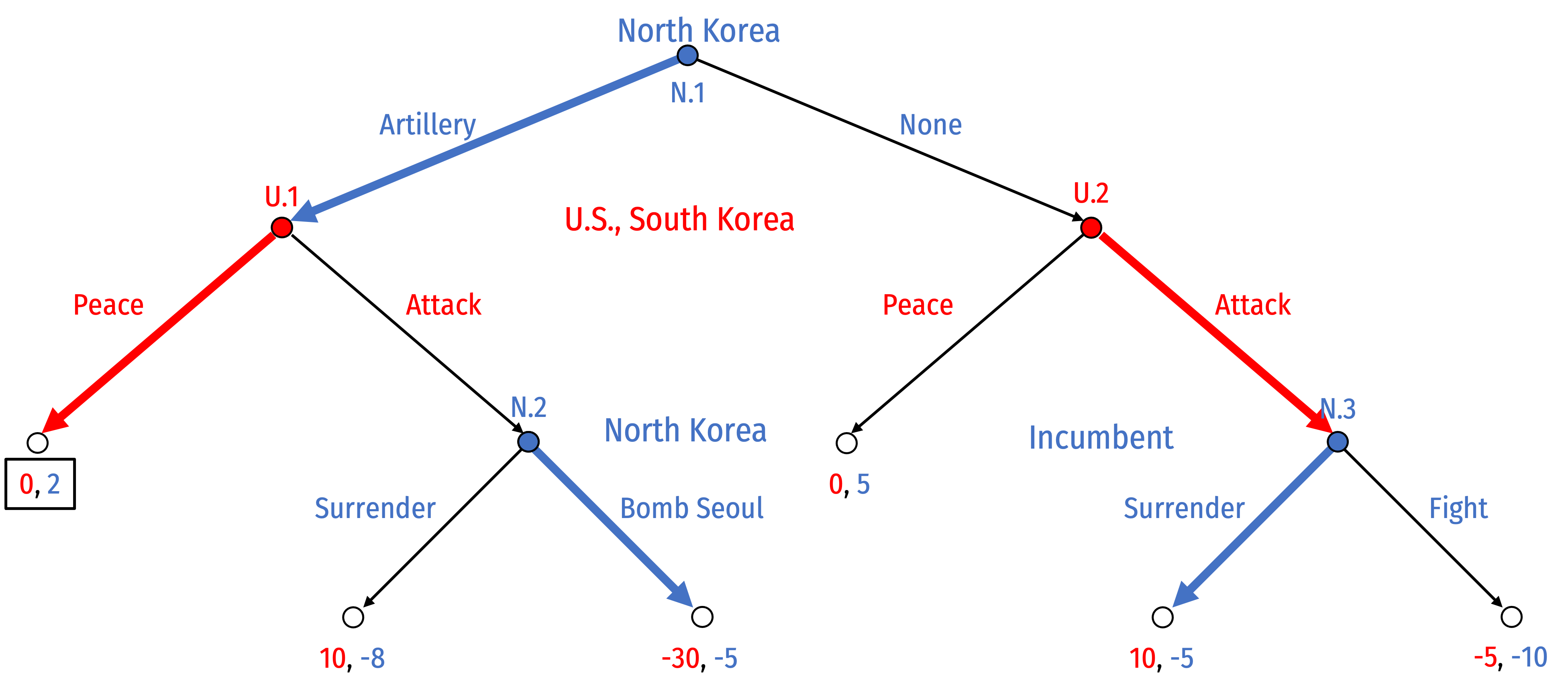

Why hasn’t the U.S. bombed North Korea?

Suppose placing and constantly hiding artillery costs North Korea -3

Why The U.S. Hasn’t Bombed North Korea

Why hasn’t the U.S. bombed North Korea?

Suppose placing and constantly hiding artillery costs North Korea -3

A credible threat to Bomb Seoul in response to a U.S. Attack

Promises and Applications

Promises

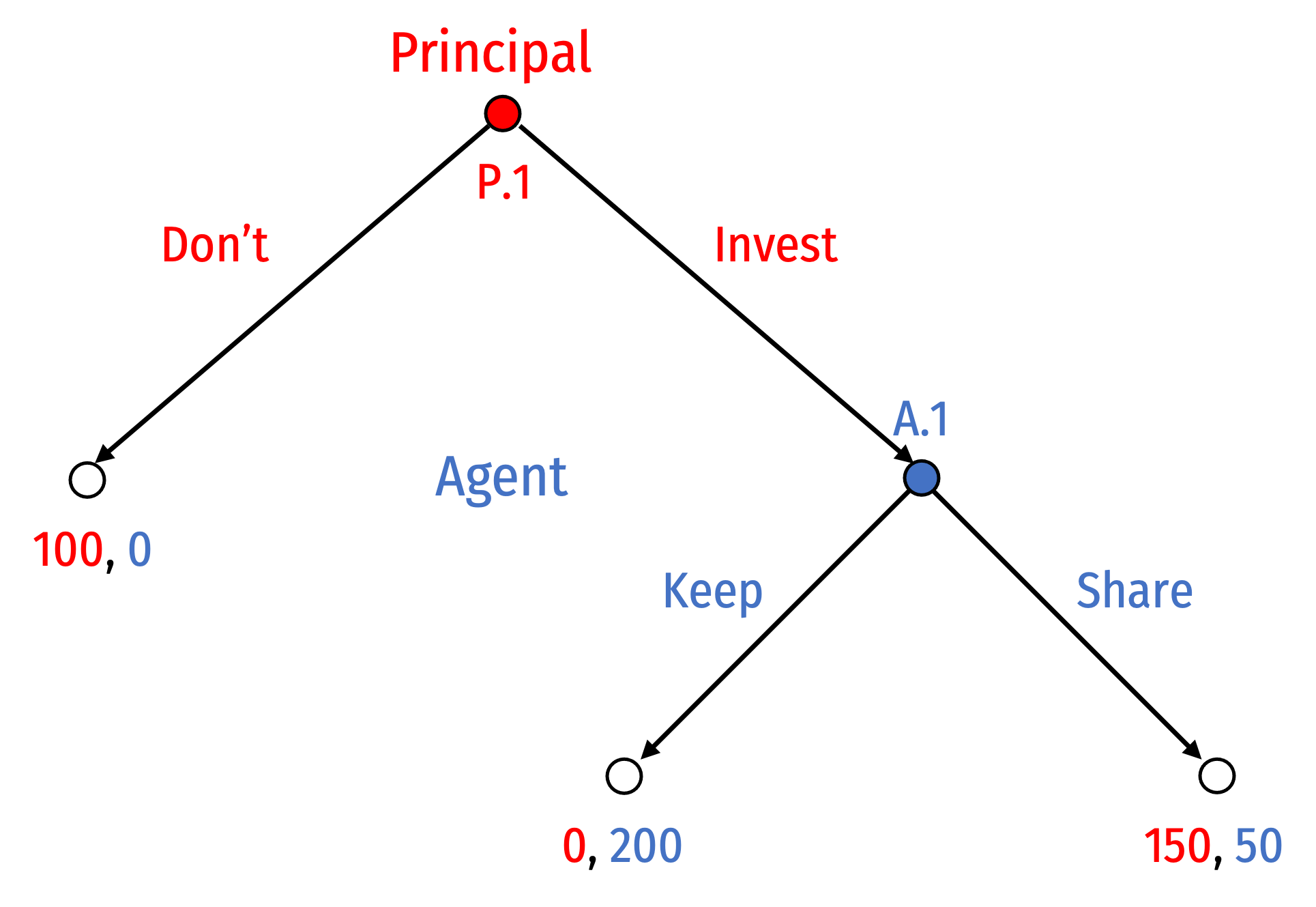

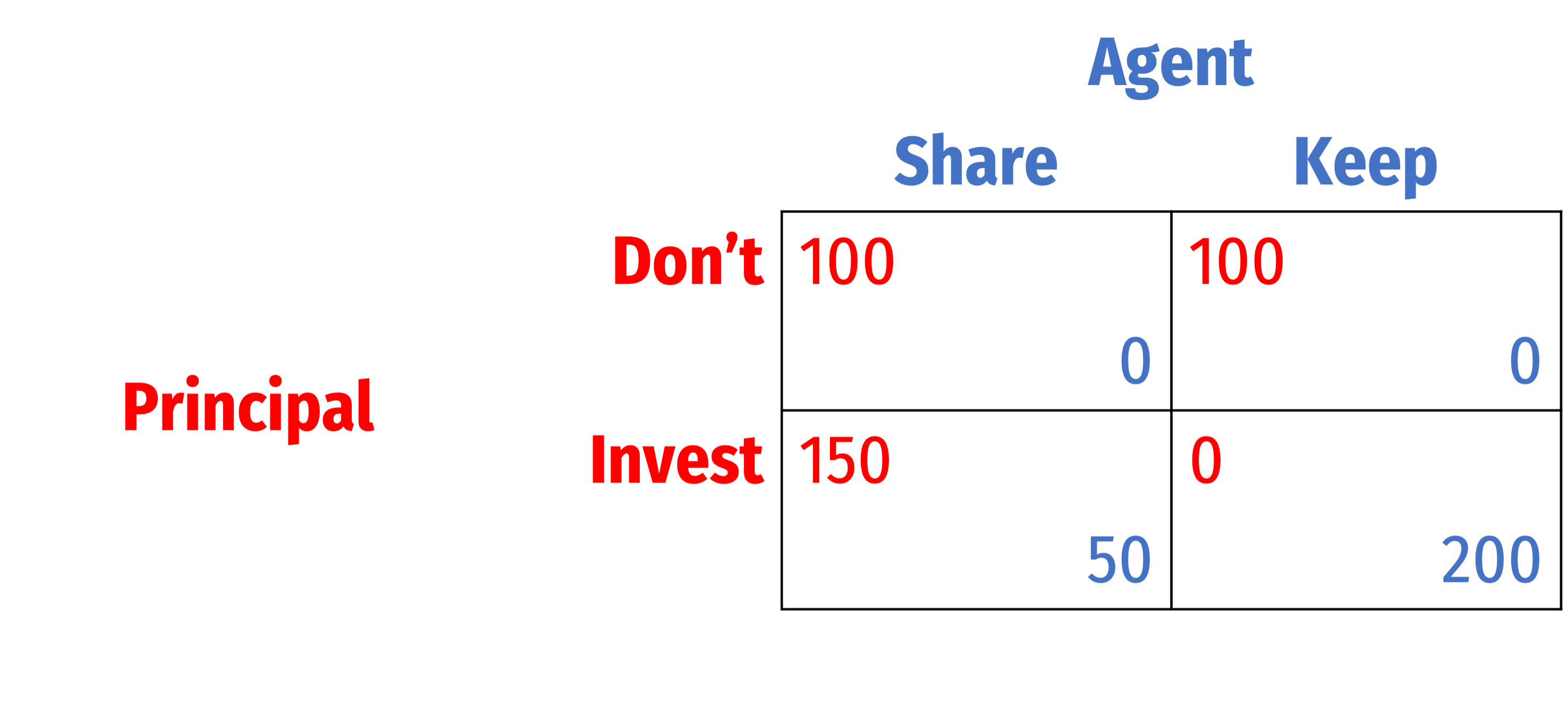

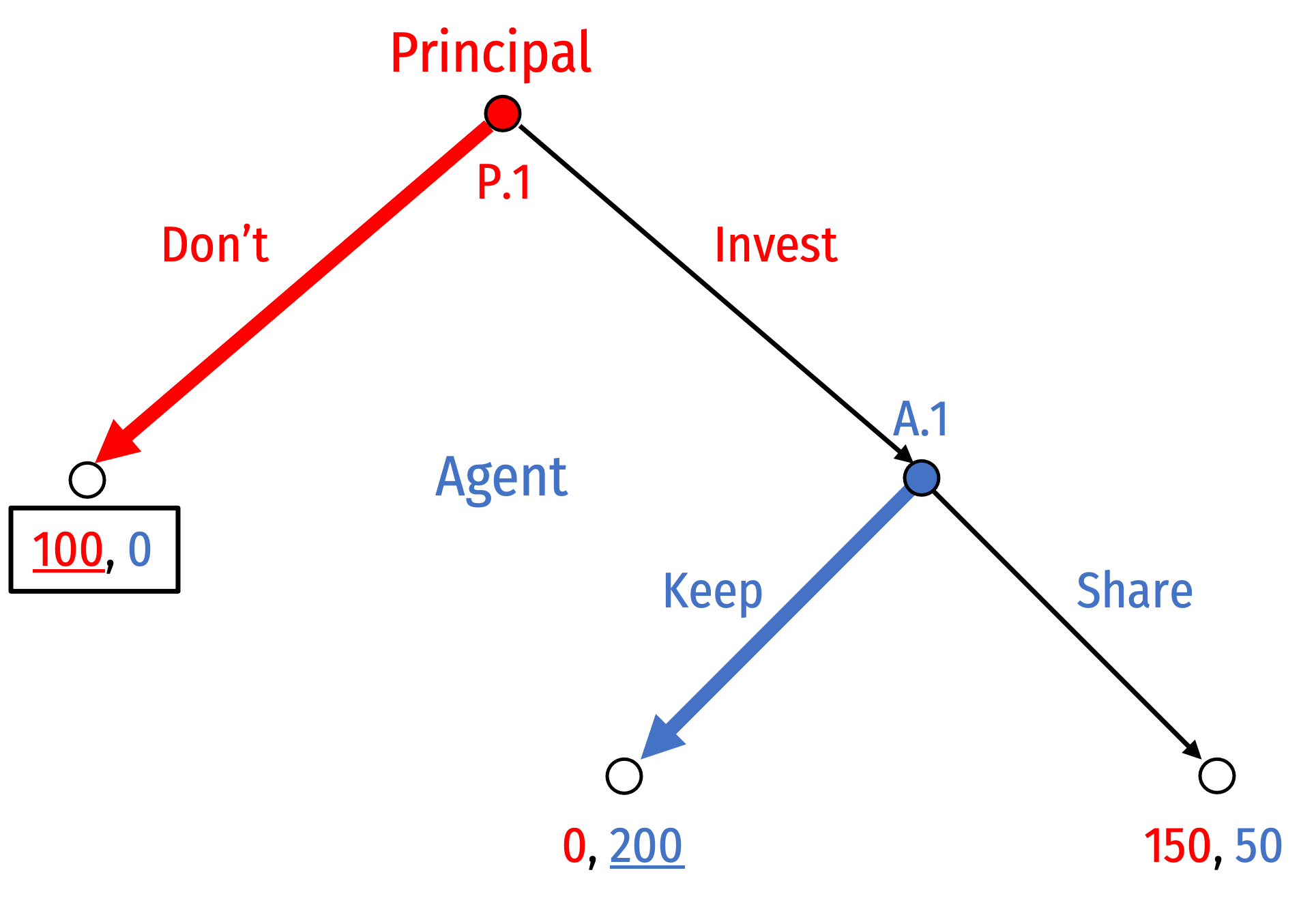

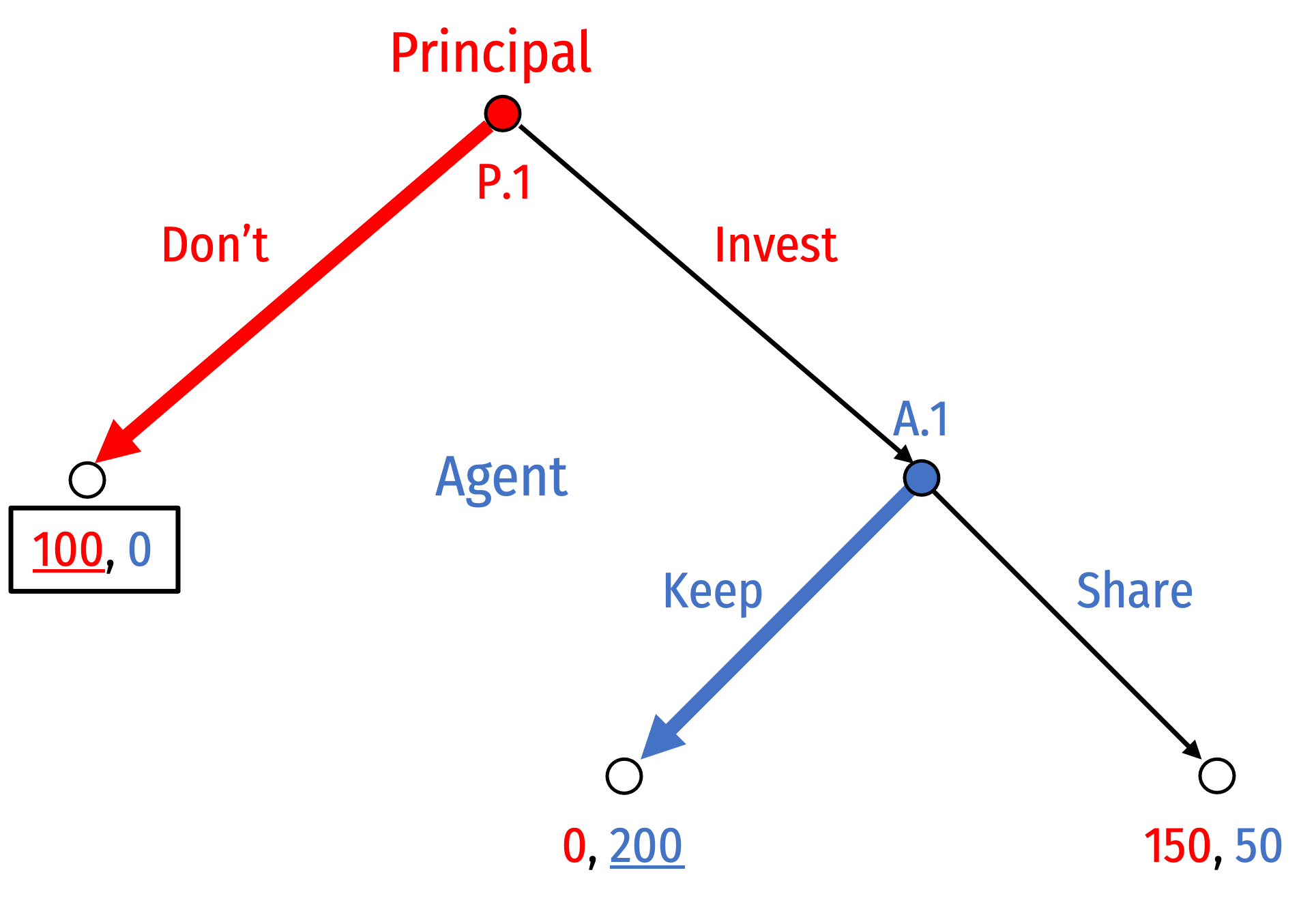

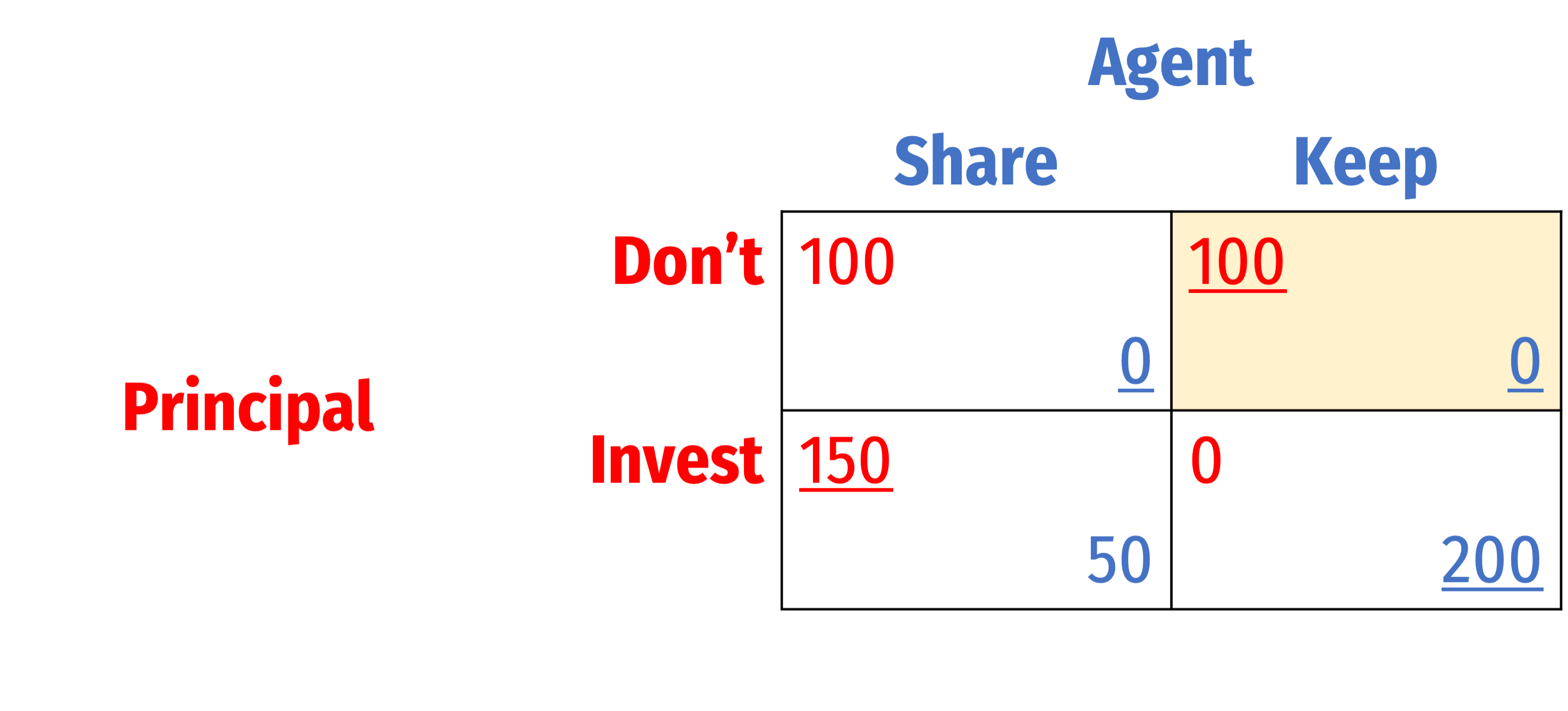

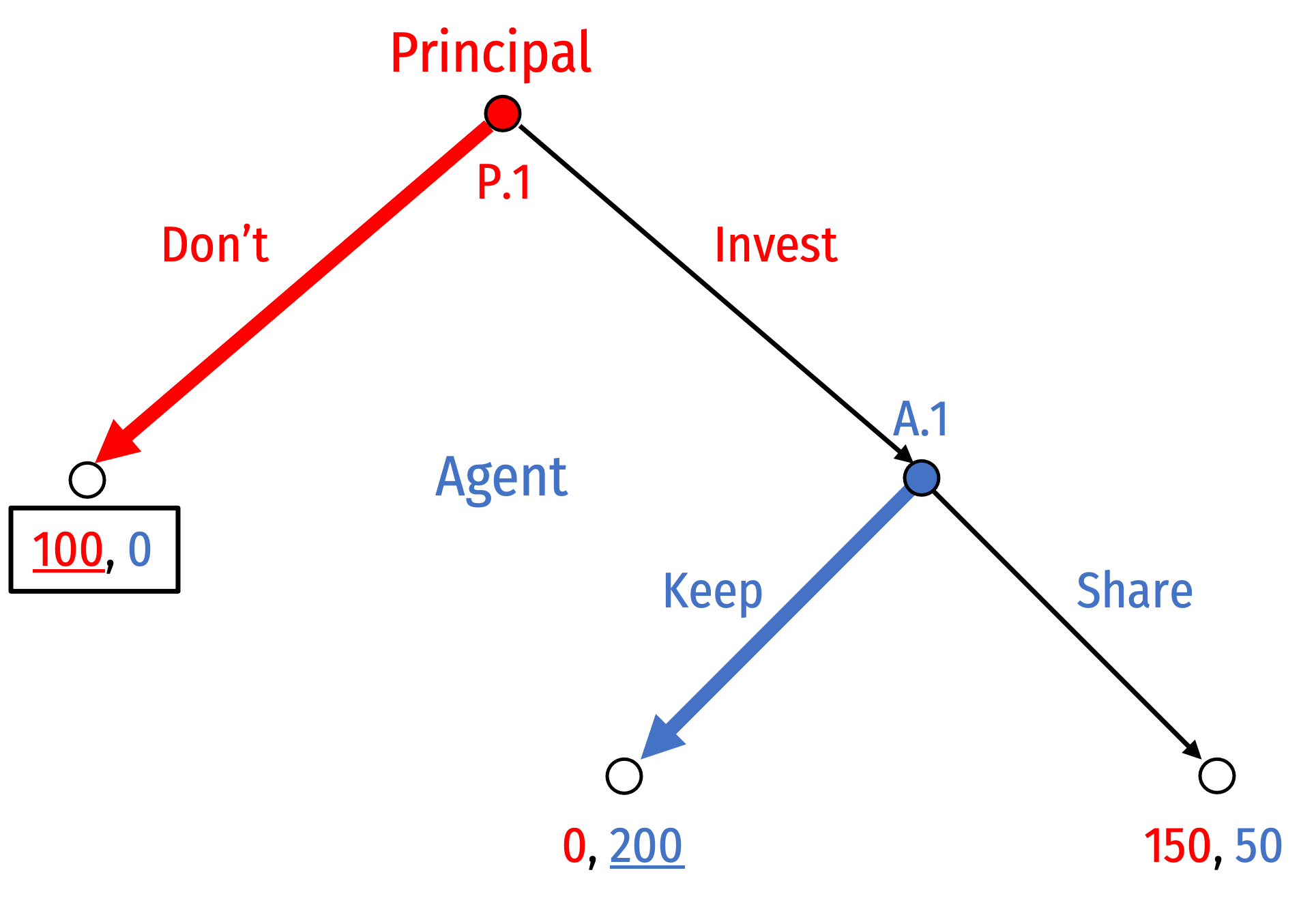

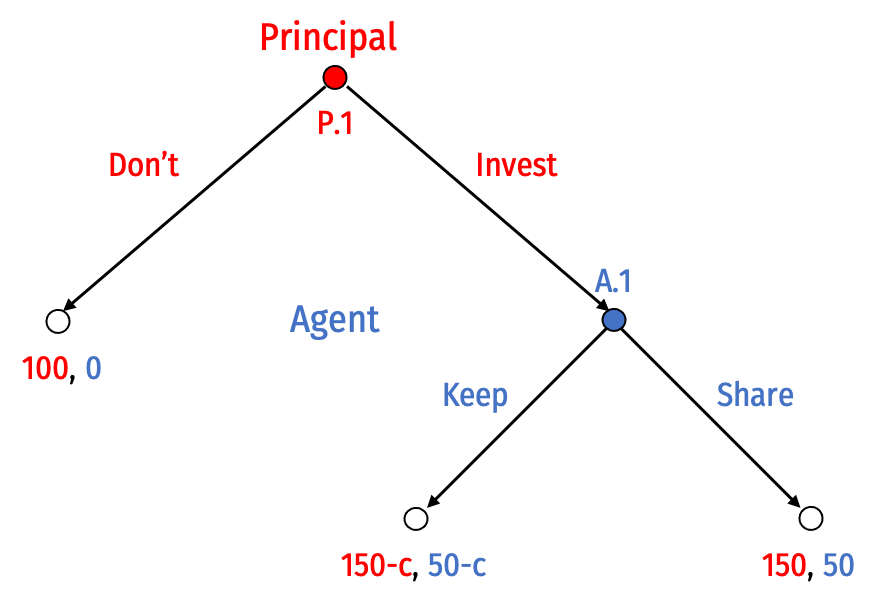

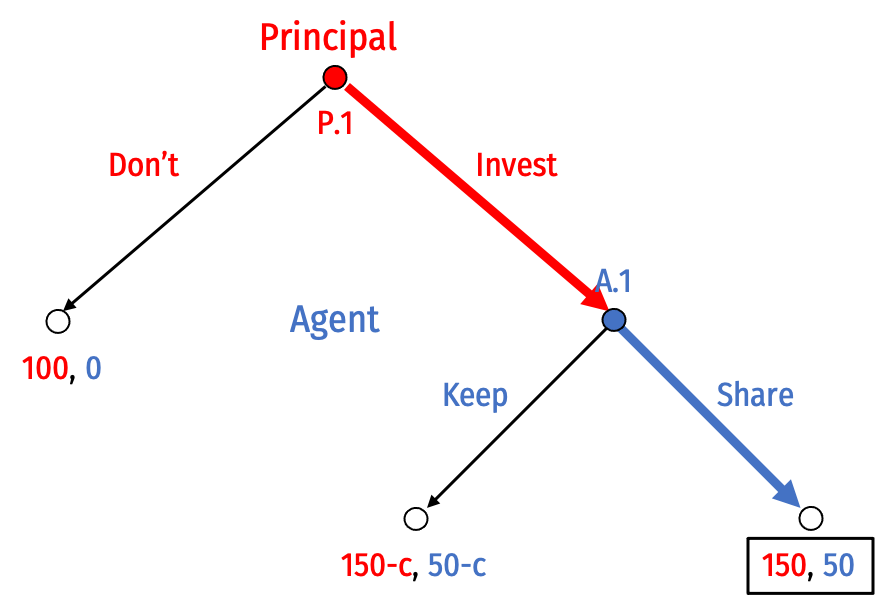

Consider again the agency/investment/trust game

Principal decides to invest money ($100) with Agent

- Investment grows to $200

Agent can then keep or share the returns with Principal

Promises

- Only one Nash equilibrium, which is SP: {Don't, Keep}

Promises

Only one Nash equilibrium, which is SP: {Don't, Keep}

What if before game began, Agent said to Principal:

“If you Invest, I will Share”

Promises

Only one Nash equilibrium, which is SP: {Don't, Keep}

What if before game began, Agent said to Principal:

“If you Invest, I will Share”

- Not a credible promise, not subgame perfect!

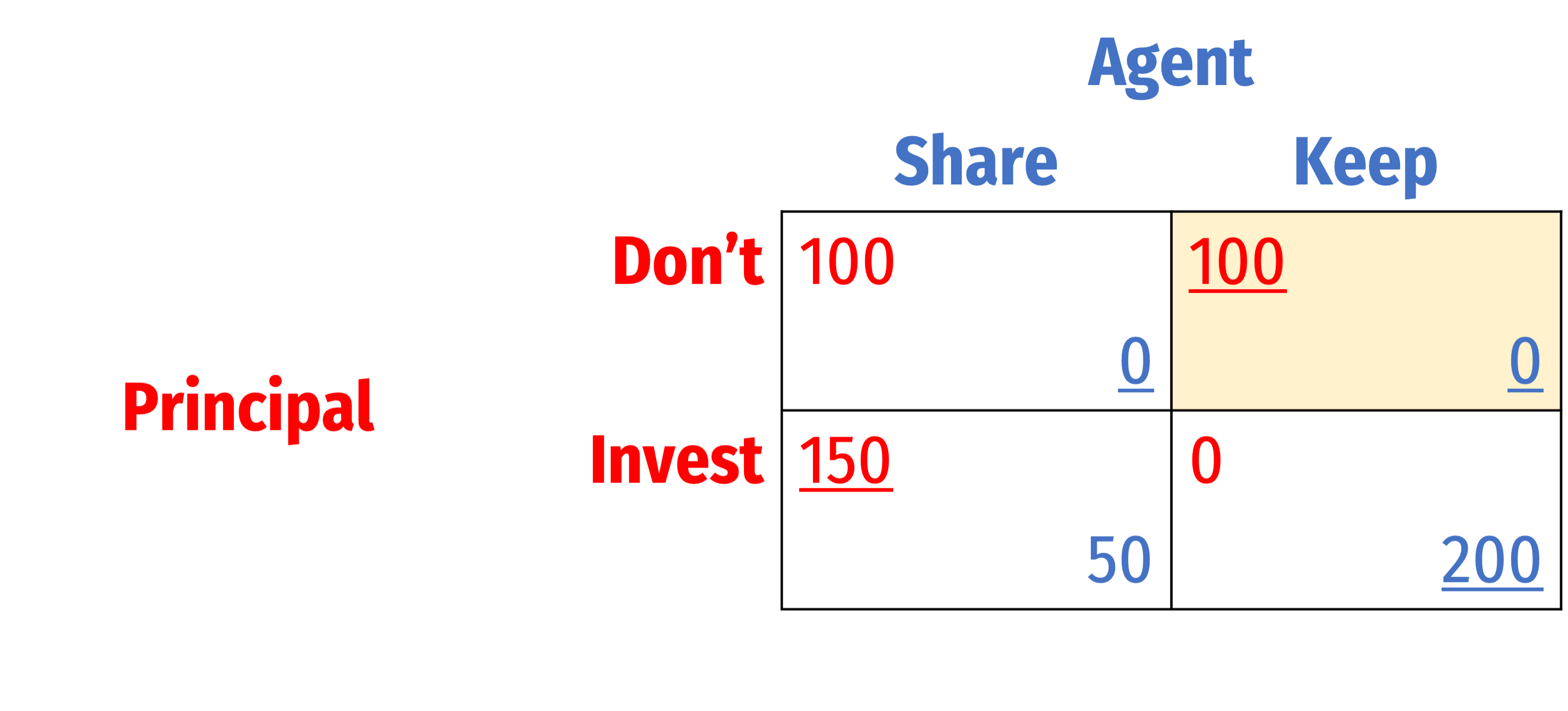

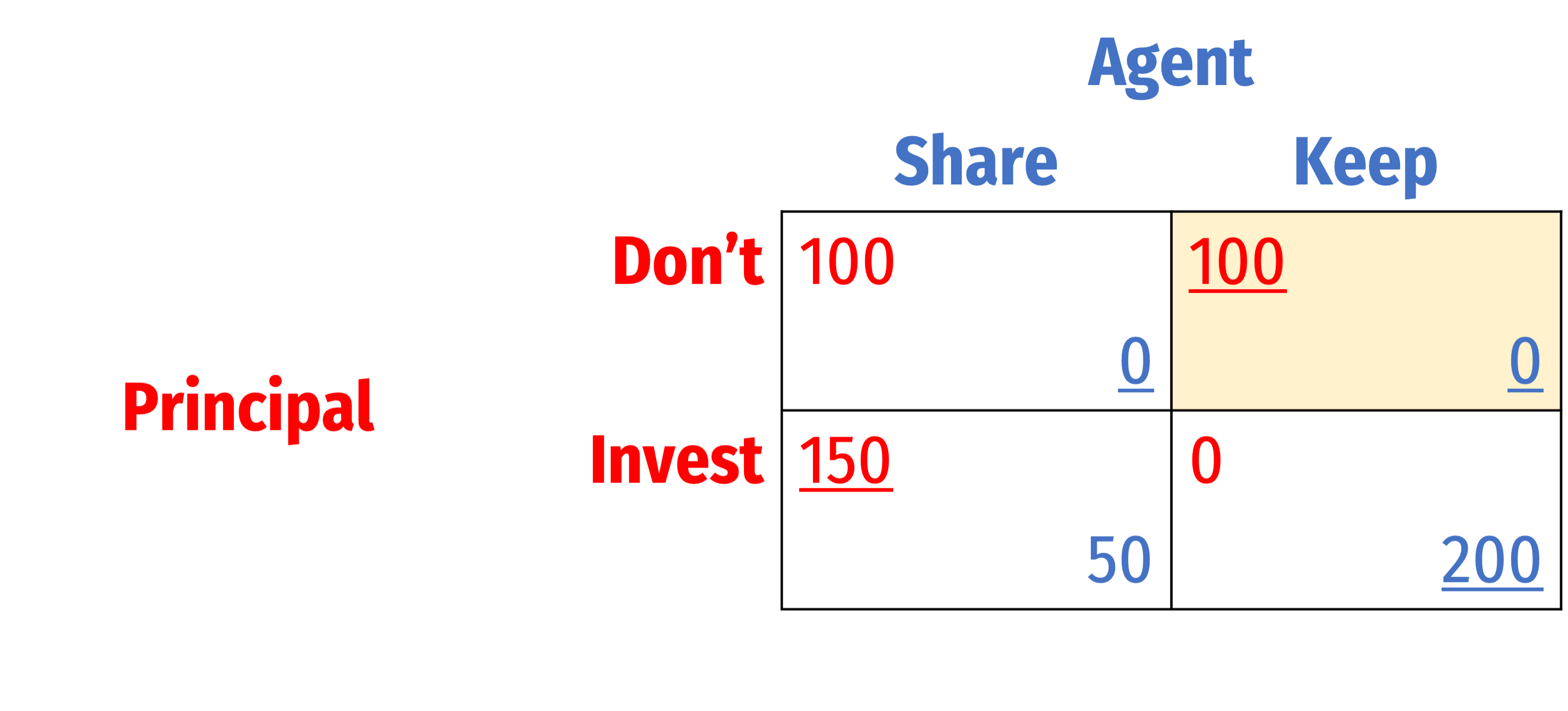

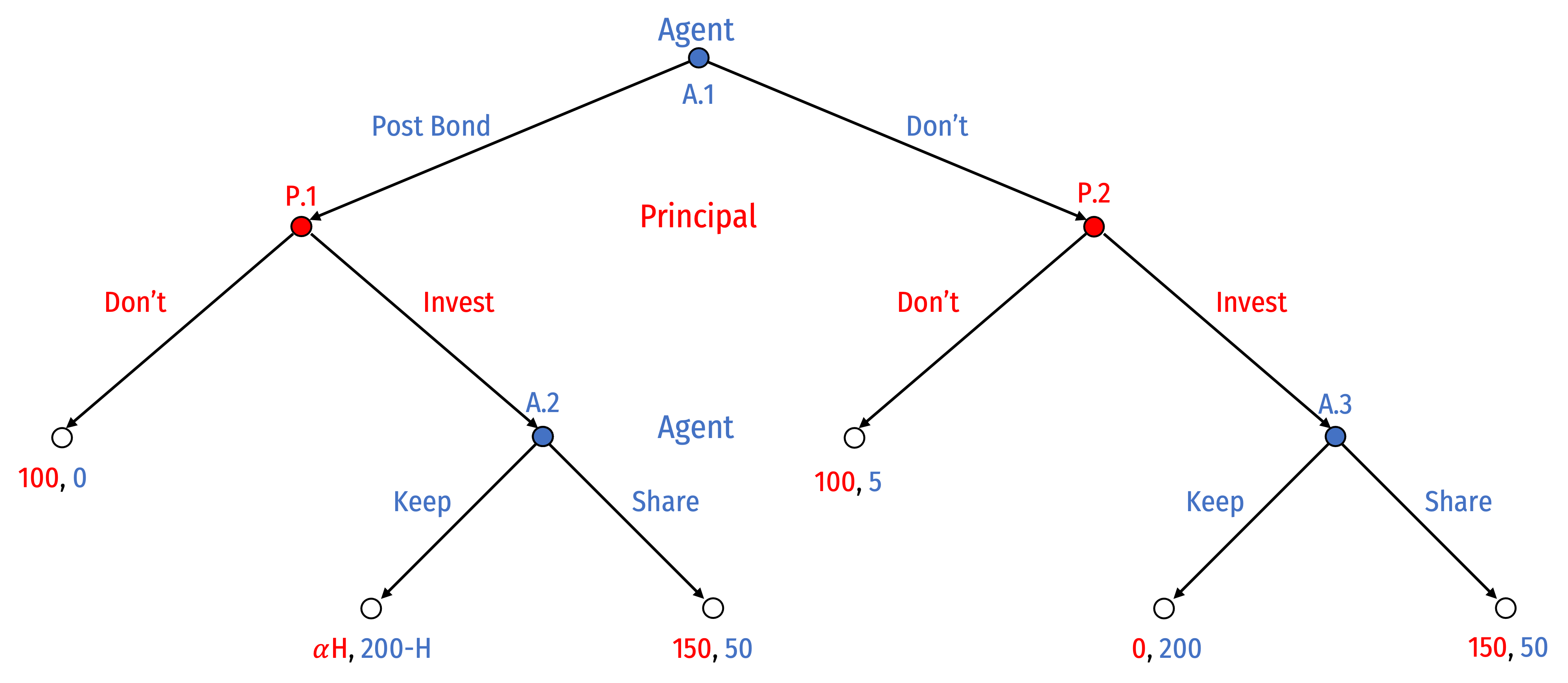

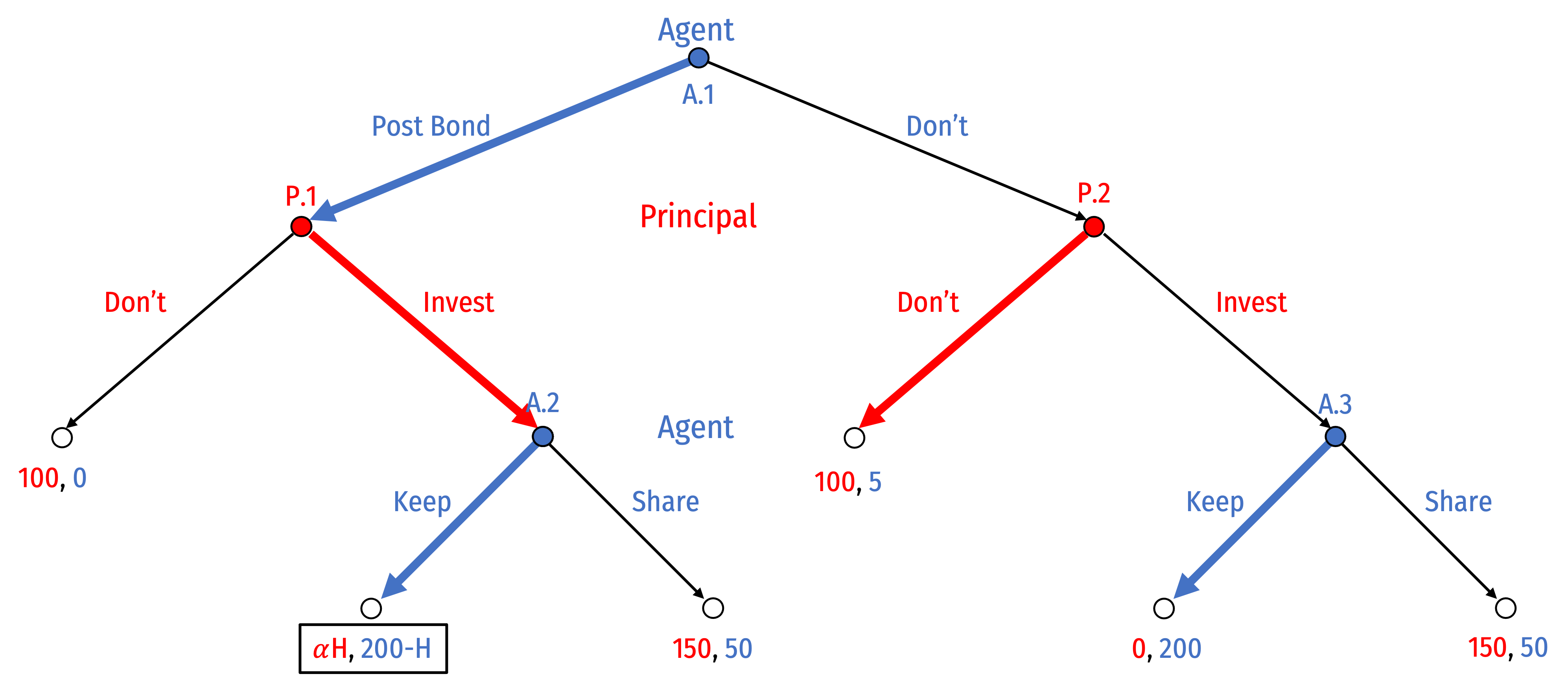

Making Promises Credible

One solution: reputation, which acts like a forfeitable bond

If Agent chooses to Keep, will lose -H, which is “hostage” value

- Principal will earn αH, where α is the faction of H that is valuable to Principal

- α=0: hostage has no value to Principal

- α=1: cash

Making Promises Credible

One solution: reputation, which acts like a forfeitable bond

If Agent chooses to Keep, will lose -H, which is “hostage” value

- Principal will earn αH, where α is the faction of H that is valuable to Principal

- α=0: hostage has no value to Principal

- α=1: cash

If H>150 and αH>100, SPNE: (Invest, Don't, Bond, Share, Keep)

Making Promises Credible

Common type of bond is reputation, which people can invest in and is “held hostage” for good behavior

- reneging on commitments destroys reputation

- works best with repeat interactions, high discount rates (folk theorem!)

Another is some collateral property that is forfeit if the contract is breached

- Mortgages, secured loans, etc

In The Old Days, These Were Actual Hostages

Williamson, Oliver E, 1983, “Credible Commitments: Using Hostages to Support Exchange,” American Economic Review 73(4): 519–540

Today We Often Hold Property Hostage as Collateral

Williamson, Oliver E, 1983, “Credible Commitments: Using Hostages to Support Exchange,” American Economic Review 73(4): 519–540

Contract Law: Making Promises Credible

- Suppose instead we have courts enforce a promise to Keep

- Court will force Agent to give $150 to Principal

- Litigation cost of using courts c to each party

Contract Law: Making Promises Credible

Suppose instead we have courts enforce a promise to Keep

- Court will force Agent to give $150 to Principal

- Litigation cost of using courts c to each party

With c>0, SPNE: (Invest, Share)

- (One main) purpose of contract law is to make promises credible

Making Promises Credible: Engagement