4.3 — Political Economy of Commitment

ECON 316 • Game Theory • Fall 2021

Ryan Safner

Assistant Professor of Economics

safner@hood.edu

ryansafner/gameF21

gameF21.classes.ryansafner.com

The Problem of Credible Commitment in Political Economy

Thomas Hobbes, Game Theorist I

Thomas Hobbes

1588-1679

"In [the state of nature], there is no place for Industry; because the fruit thereof is uncertain; and consequently no Culture of the Earth...no Knowledge of the face of the Earth; no account of Time; no Arts; no Letters; no Society; and which is worst of all, continuall feare, and danger of violent death; And the life of man, solitary, poore, nasty, brutish, and short, (Ch. XVIII).

Hobbes, Thomas, 1651, Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil

Thomas Hobbes, Game Theorist II

Thomas Hobbes, Game Theorist III

Thomas Hobbes

1588-1679

"For the Lawes of Nature (as Justice, Equity, Modesty, Mercy, and (in summe) Doing To Others, As Wee Would Be Done To,) if themselves, without the terrour of some Power, to cause them to be observed, are contrary to our naturall Passions, that carry us to Partiality, Pride, Revenge, and the like. And Covenants, without the Sword, are but Words, and of no strength to secure a man at all, (Ch. XVIII).

Hobbes, Thomas, 1651, Leviathan: Or the Matter, Forme and Power of a Commonwealth, Ecclesiasticall and Civil

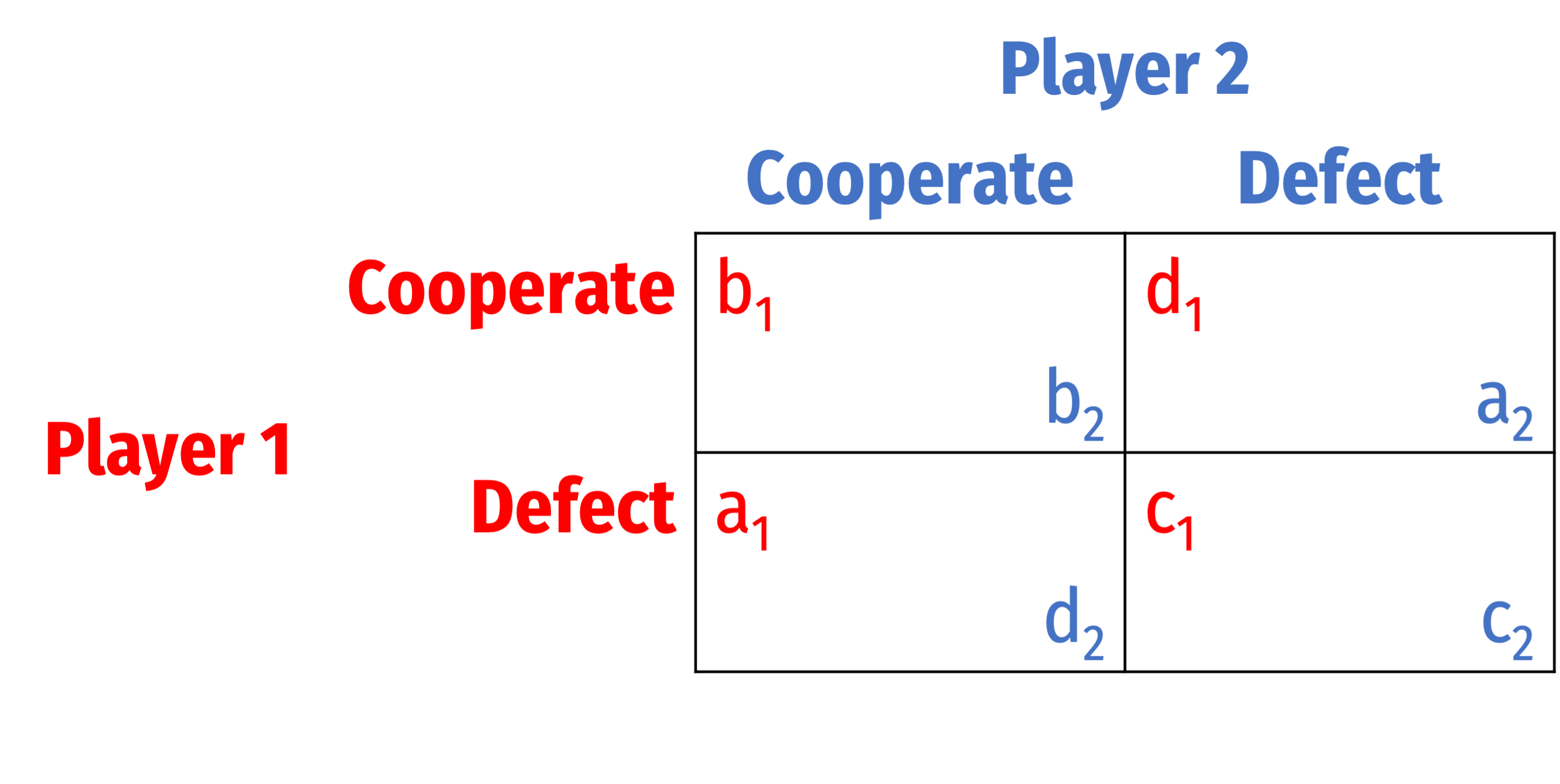

The Hobbesian Dilemma

Consider society, in general, a prisoner's dilemma for social cooperation or conflict:

- a: everyone else obeys the law, but I don't

- b: everyone obeys the law

- c: no one obeys the law

- d: I obey the law, but no one else does

Nash equilibrium: everyone defects!

Socially optimal equilibrium: everyone cooperates

Hobbes' insight: no individual has an incentive to cooperate when everyone defects!

a≻b≻c≻d

The Hobbesian Solution I

The Hobbesian Solution II

The State is our commitment device

Citizens (in principle) sign a social contract, i.e. a "constitution" that deliberately restricts their liberties

In each of our interests to give up some liberties that restrict the liberties of others (e.g. theft, violence)

In exchange, we empower the State as our agent to punish those of us that fail to uphold the social contract

Politics: rules which we agree are legitimate, that determine an outcome for us all, even if we disagree (or are harmed by) with the outcome

The State

Max Weber

1864-1920

"[A] State is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory."

Weber, Max, 1919, Politics as a Vocation

Madison's Paradox I

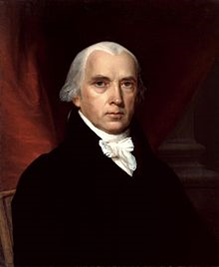

James Madison

1751-1836

“If men were angels, no government would be nec- essary. If angels were to govern men, neither external nor internal controls on government would be necessary. In framing a government which is to be administered by men over men, the great difficulty lies in this: you must first enable the government to control the governed; and in the next place oblige it to control itself,” (Federalist 51).

Hamilton, Madison, & Jay, 1788, The Federalist Papers

Madison's Paradox II

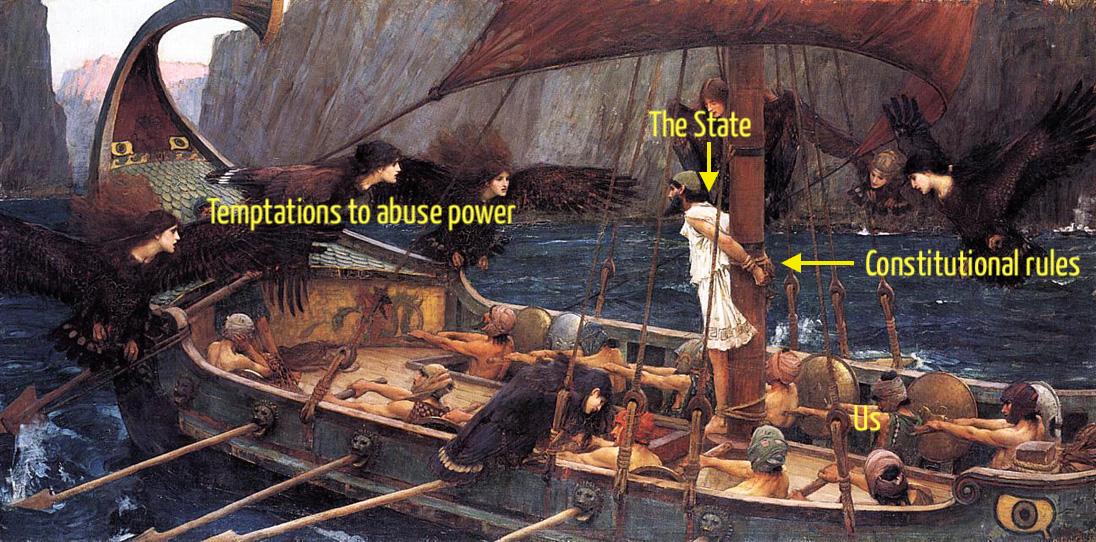

- Madison’s Paradox: a State strong enough to protect rights is strong enough to violate them at its discretion

Credible Commitment

Odysseus and the Sirens by John William Waterhouse, Scene from Homer's The Odyssey

Credible Commitment

Odysseus and the Sirens by John William Waterhouse, Scene from Homer's The Odyssey

Constitutions Are Not Self-Enforcing

Constitutions Are Not Self-Enforcing

George W. Bush

43rd President of the U.S.

“Stop throwing the constitution in my face, the constitution is just a goddamn piece of paper!”

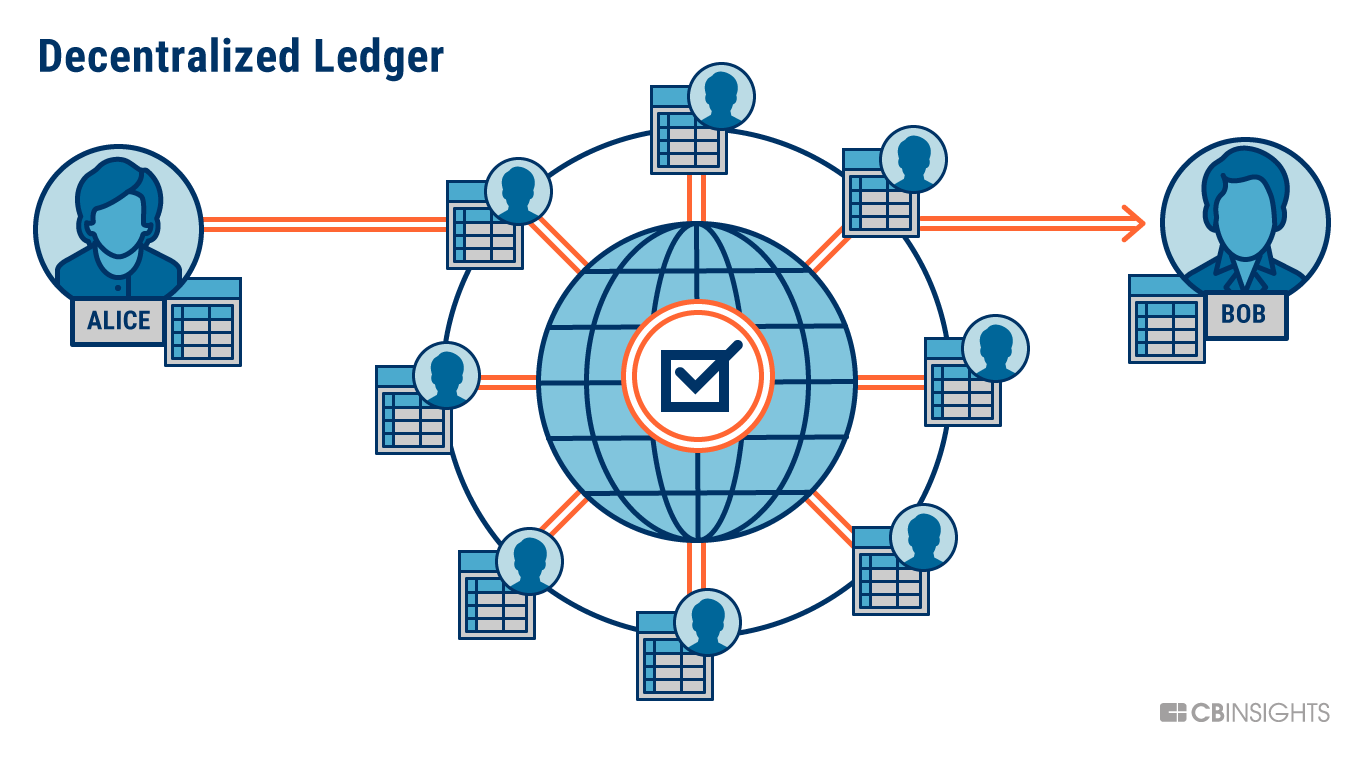

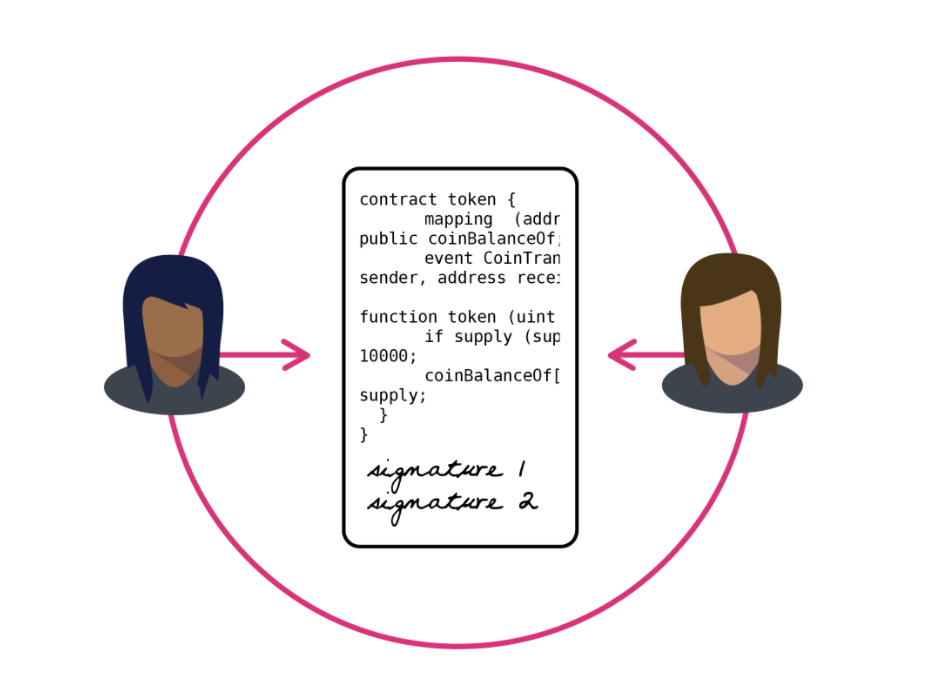

Aside: Perhaps We Have a New Alternative

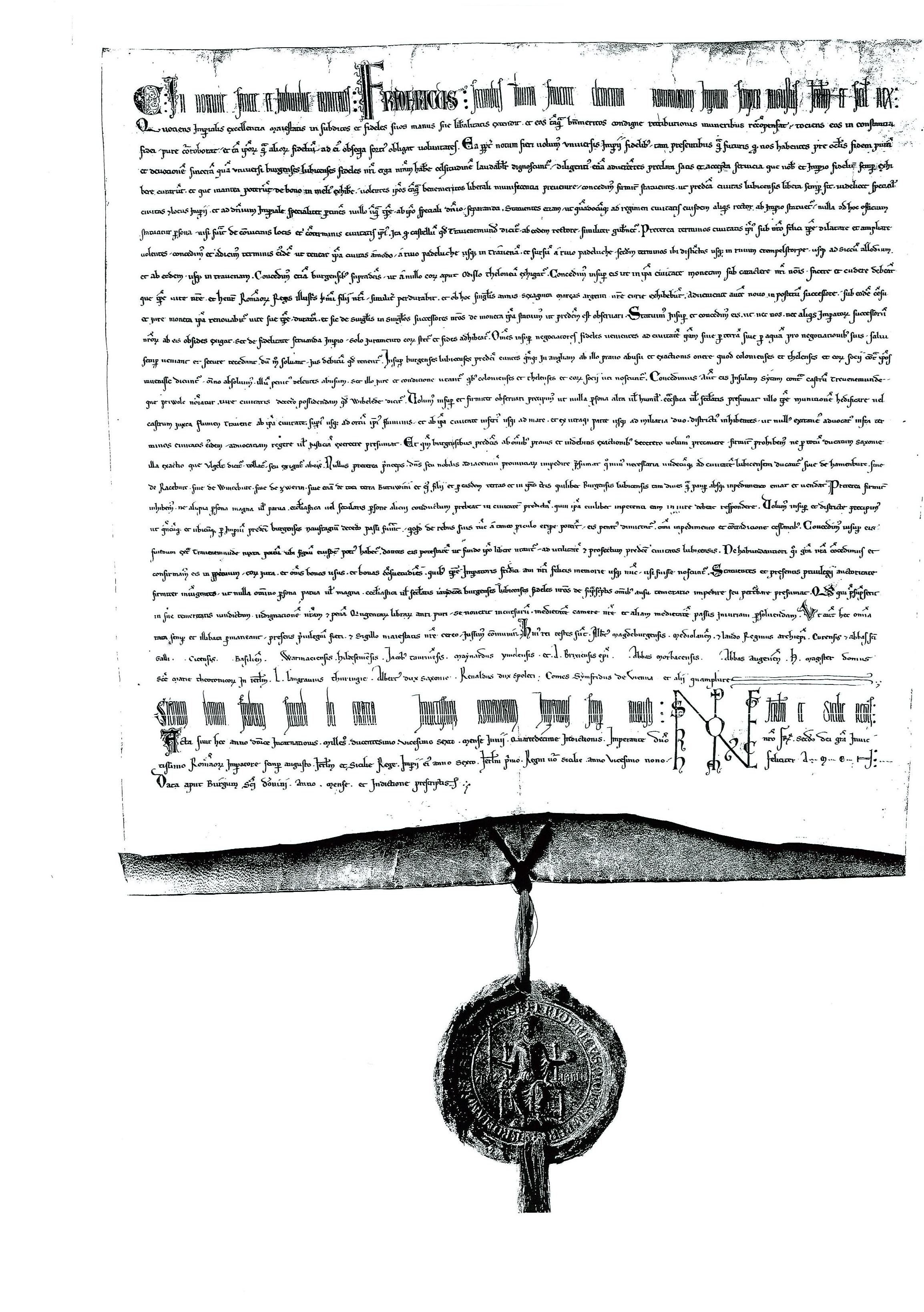

Application I: How Medieval Guilds Promoted Trade

The Commercial Revolution & Revivial of International Trade (c.1100-c.1300)

The Revival of International Trade (c.1100) I

The Commercial Revolution

- Long distance trade in Medieval Europe based on exchange of goods brought from different parts of the world to central trade fairs

Milgrom, Paul R, Douglass C North, and Barry R Weingast, (1990), "The Role of Institutions in the Revival of Trade: The Law Merchant, Private Judges, and the Champagne Fairs," (Economics and Politics*2(1): 1-23

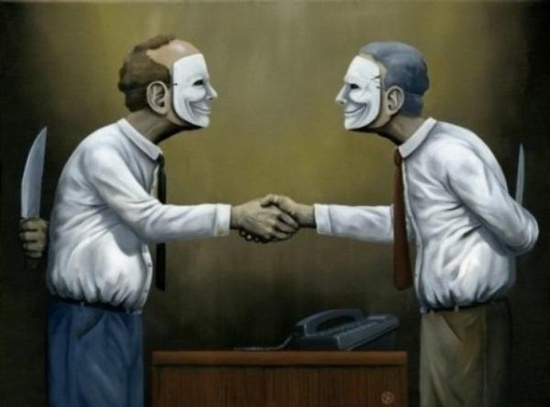

Credible Commitments

Rulers (kings, queens, emperor, lords) face certain incentives:

- Trade is an attractive source of wealth (along with plundering and warfare)

- Rulers have a strong incentive to create trading cities: potential tax revenue

Often granted cities and merchants privileges and exemptions from feudal duties

- Medieval towns as first proto-capitalist centers of specialization and trade

Credible Commitments

Trade requires peace & stable property rights

- Merchants, particularly foreign merchants, are easy pickings for a corrupt ruler

After a ruler promises to protect trade, incentives arise for him/her to renege on promise!

- How can rulers credibly commit to not confiscate the goods of foreigners?

Credible Commitments

- The“Commercial Revolution” of 1100s-1200s

- large increase in international trade

- made possible by new institutions and shifting political power

Medieval guilds, leagues of city-states

Coalition and reputation system

Merchant law

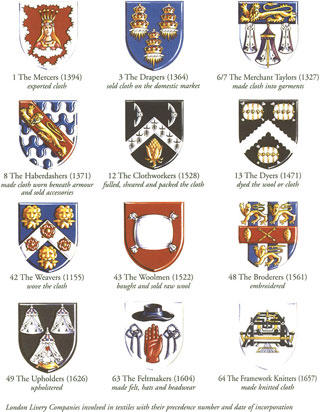

The Role of Medieval Guilds in Promoting Trade

We often think of Medieval guilds as just monopolies or cartels meant to restrict trade

- This is true

But in a way they also promoted trade

- Were set up by merchants to reduce transactions costs

- Solved credible commitment problems for rulers

Greif, Avner, Paul, Milgrom, and Barry Weingast, 1994, "Coordination, Commitment, and Enforcement: The Case of the Merchant Guild," Journal of Political Economy 102(4): 745-776

The Hanseatic League

Most famous guild: Hanseatic League (German “Hansa”) of Northern Europe

The Role of Medieval Guilds in Promoting Trade

Guilds were administrative bodies

Ability to regulate trade within local region

Guilds had chapters in each city, could gain access to all guild privileges abroad

Monitored and provided information about merchant activity

- Rulers (and merchants!) who cheated, broke promises, or were corrupt were widely publicized within guild

Greif, Avner, Paul, Milgrom, and Barry Weingast, 1994, "Coordination, Commitment, and Enforcement: The Case of the Merchant Guild," Journal of Political Economy 102(4): 745-776

The Role of Medieval Guilds in Promoting Trade

Guilds allowed merchants to coordinate collective action in punishing transgressors

A free rider problem in punishment:

- individual merchant doesn’t have incentive to punish

- may have reason to get a corrupt bargain at expense of other merchants!

Violating merchants would have their privileges revoked, or be expelled from guild

Untrustworthy rulers would be boycotted by entire guild across Europe

- Even a case of the Hanseatic League going to war!

- 1358 Hansa embargo of Bruges

“It was announced that any disobedience, whether by a town or an individual, was to be punished by perpetual exclusion from the Hansa”

The Role of Medieval Guilds in Promoting Trade

- Threat of collective punishment enables rulers to credibly commit to protect merchant rights

- removes ruler’s temptation of a one-time expropriation

- threatens infinite future punishment (think trigger strategy in game theory)

Greif, Avner, Paul, Milgrom, and Barry Weingast, 1994, "Coordination, Commitment, and Enforcement: The Case of the Merchant Guild," Journal of Political Economy 102(4): 745-776

Application II: Market-Preserving Federalism

Federalism

William H. Riker

1920-1993

“A political system is federal if is has both

A hierarchy of governments, each is autonomous in its own well-defined sphere of authority

The autonomy of each government is institutionalized in a manner that respect is self-enforcing”

Quoted in Weingast (1995) p.4

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Federalism: Necessary, but not Sufficient

Argentina is a great example of what not to do, on paper, very decentralized

Provinces have primary responsibility for education, health, poverty, housing, infrastructure, primary tax collection, etc

But all provinces' tax revenues go to national government to be redistributed back to provinces

- Most provinces finance less than 20% of their own spending

What incentives does this create?

Sanguinetti, Pablo and Mariano Tommasi, 2001, "Fiscal Federalism in Argentina: Policies, Politics, and Institutional Reform," Journal of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association

Federalism: Necessary, but not Sufficient

Provincial governments spend other people's money but tax their citizens to fund other provinces!

Thus, each province sets their spending high but taxes low

Argentine federal government has repeatedly had to bail out provinces

- Local governments face a "soft budget constraint"

Sanguinetti, Pablo and Mariano Tommasi, 2001, "Fiscal Federalism in Argentina: Policies, Politics, and Institutional Reform," Journal of the Latin American and Caribbean Economic Association

Federalism: Necessary, but not Sufficient

Federalism alone does not guarantee prosperity

Tiebout competition unleashed only under certain circumstances

Recall Madison's paradox and problem of credible commitment

How do you get (subnational) governments to respect limitations put upon them?

How can federalism be self-enforcing and market-preserving?

Market-Preserving Federalism

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

In addition to Riker's definition, for federalism to be "market-preserving", must also:

3) subnational governments have primary regulatory responsibility over the economy

4) a common market is ensured

5) lower governments face a hard budget constraint

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Market-Preserving Federalism

National government's authority to intervene in economy must be limited (left primarily to States)

States more subject to Tiebout competition than federal government

- Credible threat of exit as constraint on State governments' fiscal and regulatory abuse, rent-seeking

Congress passed 352 bills in 2013-2014, States passed over 45,000 (Source)

Market-Preserving Federalism

Constitution guarantees a common market, States cannot put up internal barriers or taxes against other States

- Again, ensures Tiebout competition, freedom to relocate, limits rent-seeking

Local governments must not be (even tacitly!) bailed out by federal government

- Many U.S. States have balanced budget requirements

- Federal bailouts would loosen fiscal discipline

Market-Preserving Federalism: Game Theory

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

"The fundamental political dilemma of an economic system is this: A government strong enough to protect property rights and enforce contracts is also strong enough to confis- cate the wealth of its citizens. Thriving markets require not only the appropriate system of property rights and a law of contracts, but a secure political foundation that limits the ability of the state to confiscate wealth," (p.1)

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Market-Preserving Federalism: Game Theory

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

"The answer concerns the design of political institutions that credibly commit the state to preserving markets, that is, to limits on the future political discretion with respect to the economy that are in the interests of political officials to ob- serve...these limits must be self-enforcing...political officials must have an incentive to abide by them," (p.2, emphasis in original).

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Weingast's Model: Legitimacy

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

Citizens hold beliefs about appropriate bounds on government action

- But heterogeneous: a coordination problem between citizens agreeing on what is legitimate

- Even if citizens agree, what actually happens when government oversteps those bounds?

Constraints only work if citizens react in concert against government's violations of those constraints!

- Must hold sufficiently similar views

- Citizens must punish government when it oversteps

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Weingast's Model: Legitimacy

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

"In the language of game theory, we are searching for an equilibrium to a game in which the government has the opportunity to violate constraints but chooses not to" (p. 10)

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Weingast's Model: Game Setup

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

- Single sovereign, S and two groups of citizens, A and B

A and B hold different views about the legitimate boundaries of S

Sovereign needs the support of at least one group to maintain power

Game moves as follows:

- S may decide to transgress against the rights of A, B, both, or neither

- A and B move simultaneously, may challenge or acquiesce to the sovereign

- If both challenge, S is deposed

- If only one challenges, (or neither), S's transgression succeeds

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Weingast's Model: Game

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Weingast's Model: Game

Barry R. Weingast

1952-

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Weingast's Model: Results

Need institutions to coordinate agreement on beliefs about what constitutes an infringement of rights

Very long story short: constitutions (written, like the U.S. Constitution, or unwritten, like the U.K.) allow citizens to coordinate their beliefs to allow a sovereign to credibly commit to not overstepping bounds

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Weingast's Model: Results

Local governments generate economic growth

Leads to more local tax revenue, rents for officials

Local governments have strong interest in preserving markets, preserves their own interests (tax revenue)

Weingast, Barry R, 1995, "The Economic Role of Political Institutions: Market-Preserving Federalism and Economic Development," Journal of Law, Economics, & Organization 11(1): 1-31

Application III: Rationalist Explanations for War

Fearon’s Puzzle: Violence is Inefficient

Violence is always costly: reduces joint-income of parties

- Transfer of resources to victor (not inefficient)

- Deadweight loss: costs of investment in offense and defense (inefficient)

- Some resources (and people) are also destroyed in the fighting

Purely rational agents will choose conflict if MB>MC but: a bargain is always preferable to conflict (cheaper)!

- Even a bargain where a party loses significant resources ≻ warfare

- Assuming parties bear the full cost of their actions

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Fearon’s Puzzle: Violence is Inefficient

James Fearon

1963-

“As long as both sides suffer some costs for fighting, then war is always inefficient ex post—both sides would have been better off if they could have achieved the same final resolution without suffering the costs (or by paying lower costs). This is true even if the costs of fighting are small, or if one or both sides viewed the potential benefits as greater than the costs, since there are still costs. Unless states enjoy the activity of fighting for its own sake, as a consumption good, then war is inefficient ex-post,” (p.383).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Fearon’s Puzzle: Violence is Inefficient

James Fearon

1963-

“The central question, then, is what prevents states in a dispute from reaching an ex ante agreement that avoids the costs they know will be paid ex post if they go to war?" Giving a rationalist explanation for war amounts to answering this question,” (p.383).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Explanations for War in Literature

- Leaders/societies are irrational

- barbaric impulses, megalomania, overconfidence, bigotry, etc

- overestimate own strength, underestimate opponents' strength

- Rational leaders do not internalize the costs of war

- a negative externality: leaders may start a war, but the soldiers and civilians bear the costs

- wars are therefore over-produced

- If not 1-2, it may still be rational for leaders to go to war under certain conditions

- This is Fearon's focus

Fearon’s Puzzle: Violence is Inefficient

James Fearon

1963-

“The central question, then, is what prevents states in a dispute from reaching an ex ante agreement that avoids the costs they know will be paid ex post if they go to war?" Giving a rationalist explanation for war amounts to answering this question,” (p.383).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Fearon’s Puzzle: Violence is Inefficient

James Fearon

1963-

“I propose that there are three defensible answers, which take the form of general mechanisms...In the first mechanism, rational leaders may be unable to locate a mutually preferable negotiated settlement due to private information about relative capabilities or resolve incentives to misrepresent such information...Second, rationally led states may be unable to arrange a settlement that both would prefer to war due to commitment problems, situations in which mutually preferable bargains are unattainable because one or more states would have an incentive to renege on the terms,” (p.381).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Rationalist Explanation I: Asymmetric Information

- Rationalist cause for war: asymmetric information

- parties do not know their relative strengths in violence potential

- parties may know own military strength, but not opponents

- have incentives to distort signals to other players

Rationalist Explanation I: Asymmetric Information

James Fearon

1963-

“As argued by John Harsanyi, if two rational agents have the same information about an uncertain event, then they should have the same beliefs about its likely outcome. The claim is that given identical information, truly rational agents should reason to the same conclusions about the probability of one uncertain outcome or another. Conflicting estimates should occur only if the agents have different (and so necessarily private) information,” (p.392).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Rationalist Explanation I: Asymmetric Information

Allen, Douglas W., and Vera Lantinova, 2013, “The Ancient Olympics as a Signal of City-State Strength,” Economics of Governance 14: 23-44

Rationalist Explanation I: Asymmetric Information

Rationalist Explanation I: Asymmetric Information

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

- Rationalist cause for war: credible commitment problems

- there exists a mutually-agreeable bargain preferable to war by both parties

- parties cannot trust each other to uphold it

- expectations about shifts in relative strengths in future can incentivize a preemptive strike

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

James Fearon

1963-

“Consider the problem faced by two gunslingers with the following preferences. Each would most prefer to kill the other by stealth, facing no risk of retaliation, but each prefers that both live in peace to a gunfight in which each risks death. There is a bargain here that both sides prefer to "war"—namely, that each leaves the other alone-but without the enforcement capabilities of a third party, such as an effective sheriff, they may not be able to attain it. Given their preferences, neither person can credibly commit not to defect from the bargain by trying to shoot the other in the back,” (p.402).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

James Fearon

1963-

“Note that no matter how far the shadow of the future extends, iteration (or repeat play) will not make cooperation possible in strategic situations of this sort. Because being the "sucker" here may mean being permanently eliminated, strategies of conditional cooperation such as tit-for-tat are infeasible,” (p.402).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

James Fearon

1963-

“Preemptive war scenarios provide the analogy. If geography or military technology happened to create large first-strike or offensive advantages, then states might face the same problem as the gunslingers,” (p.402).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

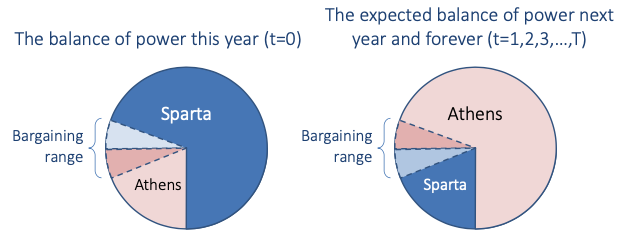

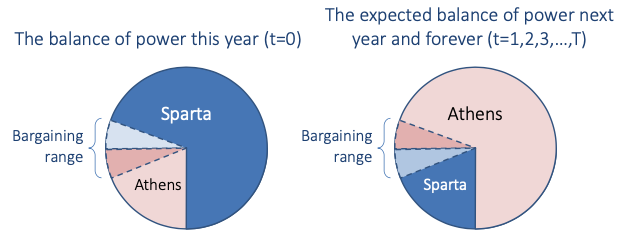

As an example, suppose the Ancient Greek world is a pie worth 100

If there is a war between Greek city states, the winner gets 100, the loser gets 0

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

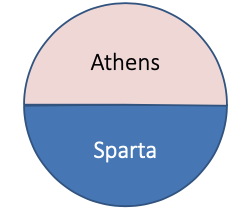

As an example, suppose the Ancient Greek world is a pie worth 100

If there is a war between Greek city states, the winner gets 100, the loser gets 0

- Fighting in a war costs 10

Suppose Athens and Sparta are equally powerful, p=0.50 chance each would win

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

As an example, suppose the Ancient Greek world is a pie worth 100

If there is a war between Greek city states, the winner gets 100, the loser gets 0

- Fighting in a war costs 10

Suppose Athens and Sparta are equally powerful, p=0.50 chance each would win

E[War]=[0.50(100)+0.5(0)]−10=[50]−10=40

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

The expected value of fighting a war is 40

This implies that Athens (for example) would find any split greater than 40 preferable to war

The cost of 10 to each side creates a bargaining range of 10+10 = 20 wide

- Athens makes an offer to Sparta of 40<x<60 to prevent war

Costly war provides incentives for a peaceful bargain

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

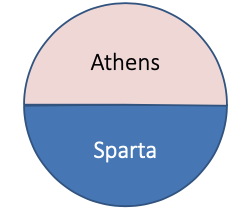

But suppose the balance of power is different, Sparta is more powerful (p=0.75) chance of defeating Athens

- War still costs each 10, plus the expected value of winning

To prevent war, Athens would have to give Sparta an offer of 65<x<85

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

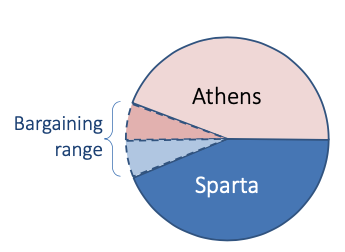

- But further suppose that while this is the distribution of power now, Athens is on the rise, and will (if unchecked), become the dominant power in the future

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

But further suppose that while this is the distribution of power now, Athens is on the rise, and will (if unchecked), become the dominant power in the future

Sparta has 75% chance to win the pie now and earn 100 forever (minus the war cost of 10)

- If it peacefully negotiates with Athens, it expects to get 25 forever

Athens needs to compensate Sparta A LOT to buy off an attack

- This amount surely exceeds Athens’ ability to pay now, cannot credibly commit to paying to prevent war in the future

Explanation II: Credible Commitment Problems

James Fearon

1963-

“In words (roughly), if B's expected decline in military power is too large relative to B's costs for war, then state A's inability to commit to restrain its foreign policy demands after it gains power makes preventative attack rational for state B,” (p.402).

Fearon, James, 1995, “Rationalist Explanations for War,” International Organization 49(3): 379-414

The Thucydides Trap

Thucydides (c. 460 B.C.-- c. 400 B.C.)

"What made war inevitable was the growth of Athenian power and the fear which this caused in Sparta," History of the Peloponnesian War.

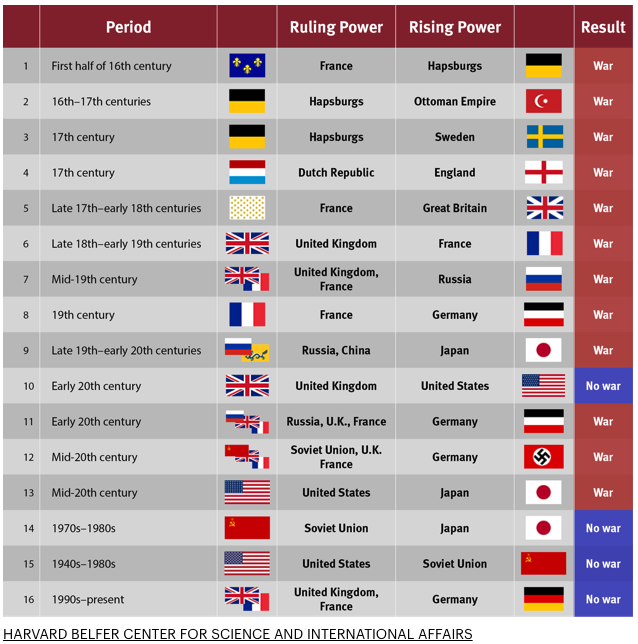

The Thucydides Trap

Graham Allison

1940—

"In 12 of 16 past cases in which a rising power has confronted a ruling power, the result has been bloodshed."

Allison, Graham, 2015, “The Thucydides Trap: Are the U.S. and China Headed for War?”, The Atlantic